“Broken promises” at Pyar Taung cement project

November 7, 2013

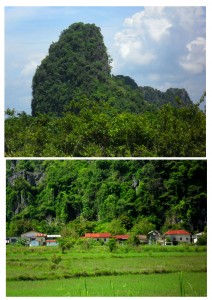

HURFOM: Thailand’s largest industrial conglomerate, Siam Cement Group (SCG), is reportedly collaborating with Pacific Link Cement Industries Ltd. to construct a 12.4 billion baht cement plant in Kyaikmayaw Township, southeast of the Mon State capital. But residents of Pyar Taung village, located on the eastern bank of the Attaran River that bisects Kyaikmayaw, have alleged that the fledgling project has been accompanied by rampant unjust land acquisition and numerous “broken promises” made to villagers by the companies.

“We already submitted letters [detailing the] damage to both local people’s livelihoods and the environment from constructing the cement project to the president, administration office and state governments,” said Nai Maung Ngo, a field researcher from the environmental and human rights watchdog Pyar Taung Watch. “Although we submitted the letter many times to the government, there are no solutions for us yet. The companies always give false statements to the residents saying that they will prevent hardships to local livelihoods, the environment, and wild animals when they call a meeting.”

“We already submitted letters [detailing the] damage to both local people’s livelihoods and the environment from constructing the cement project to the president, administration office and state governments,” said Nai Maung Ngo, a field researcher from the environmental and human rights watchdog Pyar Taung Watch. “Although we submitted the letter many times to the government, there are no solutions for us yet. The companies always give false statements to the residents saying that they will prevent hardships to local livelihoods, the environment, and wild animals when they call a meeting.”

A total of 30 workers from SCG and Pacific Link reportedly met with landowners last month in four villages along the Attaran River. According to meeting participants, company representatives made a number of promises about the value and benefits of the project and concluded by asking attendants to sign a paper without describing the significance of the document.

“We do not see any clear plans or explanation of the cement project and the worst thing is that the government is protecting the companies, so local people do not know who can speak out against the companies. The residents lived in fear of the military for many years so the companies and the authorities easily abuse them,” said Nai Maung Ngo. “One thing the residents don’t like is that the companies always want them to sign an unknown document after the meetings and the residents don’t understand why they have to sign that document. They are not sure whether it is an attendance sheet for the meeting or an authorization related to the project. The residents worry that it is a document that consents to the companies’ plan if they sign it, so they don’t want to sign. I am sure that the residents from Mac Grow, Ka Done Si, Kwan Ngan, Pauk Taw and Kaw Pa Naw villages do not support this cement project.”

He added, “Ma Khin Mar Soe, a local teacher and an employee of [one of the] companies led [the meeting]. She talked about many things regarding the companies’ promises to the residents. However, I think that an officer or administrator from the companies should give these assurances instead of the promises coming only from the workers.”

Resident Nai Kon Tar asserted that SCG, working with Thai and Burmese engineers, had already started to collect raw materials for the cement project in nearby Pauk Taw village. He said that while there had been no recent reports of environmental damage, residents had already begun to feel pressure on their traditional means of income. Local fishermen reported that ships carrying freight and construction materials along the river to the project site had severed fishing nets and created large wakes that capsized small fishing boats.

“It is not good that that kind of big ship passes in this small river because the small boat owners have to move their boats to a safe place quickly when a big ship comes. Otherwise, their small boats will capsize. But mostly the residents have lost their fishing nets because there isn’t time to pull in the nets [before the ship passes]. So we want to suggest that the big ship travels at night instead.”

Residents alleged that Pacific Link Cement had regularly taken advantage of local landowners by offering low compensation for plots of land and threatening the families who hesitated to accept the deals. In one case last month, company assistants and land record administrators surveyed Nai Ah Nyain’s plantation and offered to buy the land, but he said he would sell only for 60,000,000 kyat.

“There are seven acres of my rubber plantation that connect to the project area in Pauk Taw village and all the rubber trees on my plantation are ready for tapping. In the past, Pacific Link Cement threatened me to get me to sell the land, saying that if the government confiscated it instead, I would not be paid at all so I should accept the small price they offered. Even though I do not know about the law, I thought I would not sign due to threats because my lands would belong to them if I did. I do not like the way they threaten me to sell my land and I would rather have the government take my land than give it to these greedy businesses. I will not sign just because I am scared of their intimidation. So they have not gotten my land yet and there are some other residents like me who refuse to sign in the face of threats.”

According to villagers, when low offers of compensation were first made to landowners in early 2011, representatives of Pacific Link Cement and SCG guaranteed that they would support community development projects and reconstruct local buildings that had fallen into disrepair. However, residents said the 12-mile road connecting Ta Yana and Ka Don Si villages had yet to be renovated and the aging local school had received a fresh coat of paint but no structural repairs.

In response to recent community complaints the companies reportedly made donations by providing haircuts, schoolbooks, pencils, and an envelope with 1,000 kyat for every child. However, when the envelopes were presented to the students, the teachers allegedly confiscated the money later that day, leaving parents like Mi Shwe, 40, of Kaw Pa Naw village to wonder what the incident could mean.

“Honestly, I don’t need such a small amount of money since I have my own plantation, but [the incident] affected the relationship between the students’ parents and teachers. I feel sad because the teachers took the envelopes from the students’ hands that someone had already donated. Although there isn’t likely any relationship between the companies and the teachers, the teachers shouldn’t do that to the students. We know the reason the companies donated these small school supplies was to avoid disputes with the residents since they didn’t keep the promises they made in the past.”

Nai Nyo, a member of Pyar Taung Watch, said the project poses many controversial issues, but that educating residents about the law in order for them to defend their rights was a priority. “We all grew up under military rules so we are scared to face some problems and just want to escape, but we are trying to change those habits now. We should be brave to question the authorities or the companies if we are not clear about their plans, and we always remind the residents that we have our own rights. We want organizations based either inside or outside of Burma to train us so that we know about the laws relating to land, environment, and investment.”

The Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) released a report in October titled “Disputed Territory: Mon farmers’ fight against unjust land acquisition and barriers to their progress,” that illustrated on-going land disputes in Kyaikmayaw Township. According to the report, few victims of unjust land acquisition have had land returned, private investment continues to exploit farming families, and secure land rights remain largely absent from Burmese law.

Comments

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.