Infrastructure projects signal reform and reservations on the border

February 1, 2013

Infrastructure brings hope and fears to Eastern Burma

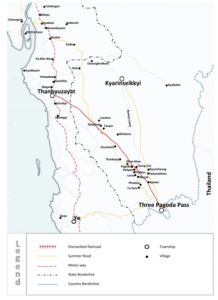

In the past few months, two remarkable infrastructure projects have been planned for the areas extending north and west of the town of Three Pagodas Pass on the Thai-Burmese border. The first entails rejuvenating a road that has been used as little more than a hunter’s footpath for over 60 years and connects the border crossing to Kyainnseikyi, a town 53 miles north. The other project is part of a high-profile proposal announced by Railway Minister U Aung Min on May 15 to reconstruct a more than 60-mile section of the “Death Railway,” a World War II-era rail line stretching 170 miles from Thanbyuzayat in Burma to Ratchaburi Province, Thailand.

To gather opinions regarding the construction plans, HURFOM collected interviews and information from the field between December 2012 and January 2013. Discussions were held with more that 45 plantation owners and villagers, in addition to members of the Karen National Union, local municipal department staff, and people close to the Shwe Chaung Zone Company, the primary contractor working on the TPP- Kyainnseikyi project.

These testimonies revealed that many people living near the two projects’ trajectories have embraced the arrival of infrastructure that they hope will improve the way they travel, live, and do business. The news that the Karen State government allotted an astonishing 700 million kyat to the rural Kyainnseikyi project appears to have been met overall with surprise and approval. However, the enthusiasm for the eastern region’s inclusion in the country’s development process was also frequently accompanied by remarks that, despite the boon, the treatment the villagers receive by local authorities and company representatives remains starkly similar to previous years under military rule. Almost all of the local people interviewed said, despite their appreciation for the efforts, they had not been given the opportunity to consult with relevant authorities or ask questions about how their homes and villages will be impacted by construction. Residents often described low-levels of information sharing along with concerns about impending damage to their land and doubts about compensation.

These testimonies revealed that many people living near the two projects’ trajectories have embraced the arrival of infrastructure that they hope will improve the way they travel, live, and do business. The news that the Karen State government allotted an astonishing 700 million kyat to the rural Kyainnseikyi project appears to have been met overall with surprise and approval. However, the enthusiasm for the eastern region’s inclusion in the country’s development process was also frequently accompanied by remarks that, despite the boon, the treatment the villagers receive by local authorities and company representatives remains starkly similar to previous years under military rule. Almost all of the local people interviewed said, despite their appreciation for the efforts, they had not been given the opportunity to consult with relevant authorities or ask questions about how their homes and villages will be impacted by construction. Residents often described low-levels of information sharing along with concerns about impending damage to their land and doubts about compensation.

A key consideration is also the role of the Karen National Union (KNU) in the infrastructure projects. The entire TPP-Kyainnsikyi road and roughly 80% of the Death Railway reconstruction run through KNU-administered areas, making the group a central stakeholder in the construction efforts. The KNU has already agreed to allow the contruction efforts to proceed, and reportedly will facilitate security and project monitoring. On occasion, it has assumed the role of negotiator between local people, construction companies, and government authorities.

This relationship building is an important element of the peace process currently underway in Karen territories and the country writ large. The conflict in Karen areas, often called the world’s longest running civil war, has prevented infrastructure projects, especially the TPP-KYA renovation, from ever developing beyond proposals. In 2004, a “gentlemen’s agreement” to end hostilities was reached between the Burmese Army and KNU’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army, but collapsed in 2006. Other than this brief, informal arrangement, the KNU never entered into a ceasefire agreement with the government until January 2012, having been engaged in civil war for 63 consecutive years.

HURFOM aims to share voices from the ground in areas that are likely to be affected by these construction projects. While development is welcomed and encouraged, it should not be accompanied by anxiety among landowners and local communities. Issues related to compensation, transparency, trust building between the state governments and rural communities, and civil society participation are critical in the current transition period. Democratization must mean responsible and inclusive decision-making and fair compensation. A mechanism for consultation and problem solving would benefit the overall process, and if the projects do affect the livelihoods of local people, appropriate compensation must be readily available.

TPP to Kyainnseikyi Project

Kyainnseikyi in Karen State is a town of more than 8,000 households divided lengthwise by the Zami River. Nearby, mountains cloaked in wild jungle stand above plantations growing rubber trees, betel leaves, cashew, and arcera nuts. The road slated for renewal, which lies on the eastern bank of the waterway, was used in the past by British and Japanese troops, the latter utilizing the passage to transport rations and as an escape route to Thailand at the end of WWII. Today, the dirt road is primarily used as a footpath for hunters, and after decades of disuse, many sections have been absorbed into the landscape.

Negotiations to update the 53 miles of road between Three Pagodas Pass and Kyainnseikyi had previously been held by Karen authorities and local construction company Shwe Chaung Zone, led by U Myo Oo, but armed conflict prevented plans from moving forward. The dirt road becomes unusable during the long rainy season, and upgrades promise year-round, “three seasons” passage connecting the Thai border town to Mon State’s bustling city of Mudon to the north.

Negotiations to update the 53 miles of road between Three Pagodas Pass and Kyainnseikyi had previously been held by Karen authorities and local construction company Shwe Chaung Zone, led by U Myo Oo, but armed conflict prevented plans from moving forward. The dirt road becomes unusable during the long rainy season, and upgrades promise year-round, “three seasons” passage connecting the Thai border town to Mon State’s bustling city of Mudon to the north.

To orchestrate development projects in the area, including the new motorway, a Regional Development Committee was formed with representatives of the Karen State government, Shwe Chaung Zone Company, the KNU, and the Municipal Civil Engineering Department. The KNU entered into a partnership with the Shwe Chaung Zone Company to oversee and monitor the project, which will include construction of 52 small and medium-sized bridges to span the area’s many streams. Thus far, project stages have only included re-alignment, grading, excavating, and compacting the dirt road in preparation of the 2013 rainy season, after which asphalt can be poured. Shwe Chaung Zone has Company said 52 bridges is a lot of money will not do that this year, SCZ receives money from Karen State. By accepting the project, the Shwe Chaung Zone Company becomes responsible for motorway construction along with compensating residents that lose property or plantations during the construction.

According to a source close with Shwe Chaung Zone Company, although several TPP-based construction companies wanted to bid on the project, the company’s chairman, U Myo Oo, declined sub-contracting offers except for U Khin Zaw’s company. The road construction was split in two, with Shwe Chaung Zone starting from TPP in November and heading north, and U Khin Zaw’s company starting in December from KYA and heading south. Now, there are only 20km left to clear before the two dirt roads converge.

According to a source close with Shwe Chaung Zone Company, although several TPP-based construction companies wanted to bid on the project, the company’s chairman, U Myo Oo, declined sub-contracting offers except for U Khin Zaw’s company. The road construction was split in two, with Shwe Chaung Zone starting from TPP in November and heading north, and U Khin Zaw’s company starting in December from KYA and heading south. Now, there are only 20km left to clear before the two dirt roads converge.

On October 22, the Three Pagodas Pass General Township Administrator, U Thein Tun, held a meeting with village residents in Chaung Zone and Kyaw Pa Lu. The authorities reportedly informed the residents that in order to claim compensation for land affected by the project, they needed to have La/Na Form No. 39, a land grant certificate that has been the only officially recognized proof of land ownership since Ne Win’s Burma Socialist Programme Party was formed in 1962. U Thein Tun explained that this certificate would assure compensation equivalent to triple the value of any land or buildings damaged by the road construction.

However, as recently as one year ago, much of the area south of Kyainnseikyi was a free-fire “black” zone where Burmese military troops exerted no control and were permitted to fire at will on anyone they encountered. For decades, villagers had minimal access to large cities and restricted mobility due to frequent armed clashes, and were unable to travel to official offices for the procurement of documents. In addition, residents stated that, when buying or selling property, they traditionally observed the local custom of village headmen facilitating the deal and price setting. All three parties would sign a paper to confirm agreement on the sale, but the Karen State land survey department does not recognize these documents.

Residents claim that contractor U Khin Zaw, who is a Kyainnseikyi native familiar with the area and its history, knows how unlikely it would be for locals to possess official land documents. Yet, they say that he, too, requires the La/Na No. 39 to initiate the compensation process. Several locals approached the KNU about their concerns, alleging that U Khin Zaw has overlooked their rights in the interest of his business, and enjoys the benefit of ties to the state government and KNU.

People maintain hope that they can procure La/Na No. 39, but many reported having no idea how to get it. Accounts by peers and neighbors about the bribery involved with the process are also causing hesitation, despite the land survey department offices issuing the La/Na No. 39 document are now open in Kyainnseikyi and Three Pagodas Pass.

“I think it is acceptable to build bridges and construct the road as part of this local development project because it will be easier for the residents to transport goods and travel to other places,” said U Myoue Kyi, a Bayar Ngar Sue resident and owner of 3.5 acres of rubber and betel nut plantation who commented on his treatment by the Shwe Chaung Zone Company. “However, we, the residents were treated similarly in the past, when companies ignored the residents and plantation owners because they got permission from the authorities. Although we are living simple lives working on plantations, they should think about us. Now, it’s not like we hoped because they think that we were not important enough people to have conversations about the project. For us, although it may be a small part of the plantation that is affected, it negatively impacts our business because we depend on this land.”

Some residents reported growing around the road, despite its disuse, and are concerned that the new plan intends to realign the path to straighten its trajectory. An owner of a 5-acre rubber plantation owner said that he deliberately cultivated his trees away from the old road, but the new construction will cut through his land.

The construction project led by U Khin Zaw crossed through villager U Seik’s 5-acre rubber plantation in Bayar Ngout Toe, along with 12 other rubber plantations in the area.

“Just like mine, many [young] rubber plantations with two to five years of growth have been damaged. We put a lot of effort into working our plantations because it is our livelihoods. Since the Shwe Chaung Zone Company was given a contract by the government, they hold the power. We worry that the company will ignore [providing] compensation to the residents when the project is done. Who can guarantee or promise us that the company will pay some compensation? Therefore, all the owners of plantation held a meeting and plan to submit a letter of appeal to the KNU chairman. If there is no compensation for us, we will ask help from KNU.”

In total, 18 residents of Bayar Ngout Toe Village on the eastern bank of the Zami River complained that the a new section of road designed to straighten the old curve will split some plantations in half, but have yet to hear from the construction company about compensation.

According to monastery supporter U Htet Tu, 61, from Chaung Zone village, the project also damaged land around a temple. “Our temple’s fence and temporary accommodation building were damaged. The Shwe Chaung Zone Company has promised compensation, but we would like to suggest that the construction avoids our land.”

A monastery supporter said, “We would like them to avoid existing buildings. There is no blame on the project, but we prefer to see that Shwe Chaung Zone Company and the authorities take full responsibility for the villagers who have been affected.”

Daw Ma Kywae from Zin Kaung Village lost between 400 and 500 young rubber trees. Two Yae Lae villagers, U Htein Shwe and U Myat Lin, together lost around 300 mature rubber trees ready to be tapped. Fellow Yae Lae plantation owner U Khan Htee reported the destruction of 700 rubber trees due to the repositioning of the road’s trajectory. In January, the four residents jointly asked U Khin Zaw for compensation and were told they must either produce the La/Na No. 39 document, or else he would work with them to find another solution. They claim they have not heard from his since this exchange.

A member of the KNU liaison office said, “Construction companies have to pay compensation if the project affects the residents’ plantations, according to our agreement. Our village administrator U Shwe Maung also told the state authorities to treat residents fairly in their dealings with the companies. I suggest to the residents that they start securing land grants, either from the KNU or the government, because it will be important when they deal with companies.”

Death Railway Reconstruction Project

On May 15 last year, then-Railway Minister U Aung Min announced at a KNU opening ceremony that the Death Railway would be reconstructed. Within three or four years, he said, the new line would allow residents of TPP to quickly access Rangoon, and Burmese citizens more easily travel to Bangkok. In addition to the railway, a new motorway will replace the current road as part of the Asia Highway project and a larger effort to improve regional commerce with an industrial zone jointly led by ministers of Karen and Mon States.

Built by Japan during World War II using forced labor, approximately 100,000 Asian laborers and allied POWs were killed during the Death Railway’s construction. The track was stripped away when the Japanese army later retreated across mainland Southeast Asia, but the route continued to be used as the primary motorway connecting Three Pagodas Pass to Thanbyuzayat in central Mon State.

Built by Japan during World War II using forced labor, approximately 100,000 Asian laborers and allied POWs were killed during the Death Railway’s construction. The track was stripped away when the Japanese army later retreated across mainland Southeast Asia, but the route continued to be used as the primary motorway connecting Three Pagodas Pass to Thanbyuzayat in central Mon State.

In October, members of the Union Solidarity and Development Party met with various political representatives and businessmen to discuss the railway’s reconstruction and upgrades to key infrastructure in the TPP area. Unlike the Kyainnseikyi road repair, the rail project is large and high-profile, and is expected to involve the central government.

On November 11, a land survey group reportedly including three foreign engineers and accompanied by General Lin Oo, the Anang Kwin Village Tactical Commander No. 1 from the government military unit responsible for providing security for the surveyors, came to Three Pagodas Pass to assess the landscape. Surveys were conducted through villages, near homes and businesses, and across plantation land, and residents are unsure whether their homes may now be designated for the bulldozer. A former member of the New Mon State Party and resident of TPP said he learned that the government planned construct the two transportation routes at the same time, and lands affected by the 60-feet-wide motorway would be compensated by the appropriate ethnic groups, Karen or Mon.

Accounts collected in the area exhibited that residents do not yet know when the railway and motorway renovation project will begin, or what companies will be responsible for the construction. Although some members of the business community reported hearing that 15 companies are currently vying for construction contracts, including domestic Burmese and foreign enterprises, there have been no official statements specifying the relevant dates or parties involved. Interviews revealed fears that homes would be demolished, requiring residents to find new homes, new jobs, and maybe new plantations to work. Some also worried that their children would no longer be able to attend school due to potential food and livelihood insecurity.

Caught in the middle

Joa Hbalu is a small town of roughly 200 households, but with a vibrant economy fueled almost entirely by rubber production. Many of the families are not native to Jo Hbalu, but moved from Ye Township or Three Pagodas Pass for its desirable proximity to Thailand, where the price of rubber is higher than in Burma. Now, the location has become a source of anxiety for residents who are sandwiched directly between the Death Railway and Kyainnseikyi construction projects. While few of the locals expressed resistance to the infrastructure development, they shared a resounding call for transparency, information sharing, and fair compensation.

“Currently, there are many rubber and fruit trees on my plantation, and we cover our house expenses and our children’s school fees with the income,” said Resident Nai Shain, age 53. “If the plantation is confiscated, I would lose my livelihood since I have spent much of my money over the last 10 years on the plantation. It is impossible to start a new plantation in a new place. There are 2,000 rubber trees and it would cost 200,000 baht at the current price [to compensate the loss]. We cannot do other work; we were born into plantation work generation after generation.

Voicing a common theme that was repeatedly expressed by villagers anticipating property damage or land confiscation, Nai Shain added, “In order for us to continue our lives as Burmese citizens, I would like to make a request that the government provides us with the [land] grant [documentation] so that we can own our plantations legally.”

Nai Zaw Lwin, a 36-year-old father of three, lamented the idea that his years of labor may be lost. “There are only 500 rubber trees on my plantation. I had many challenges to overcome to own that amount of trees, and I had to work for other people’s businesses to earn money. I never dared to spend all of the money I made because I had to spend half of my earnings on the plantation. I [also] had problems with the KNU when I started my plantation. Finally, I was allowed to cultivate the trees after I begged for permission. It would be like my life was over if the plantation was confiscated or destroyed. It is the thing I possess. It covers our house expenses and our children’s future school fees.”

Nai Zaw Lwin, a 36-year-old father of three, lamented the idea that his years of labor may be lost. “There are only 500 rubber trees on my plantation. I had many challenges to overcome to own that amount of trees, and I had to work for other people’s businesses to earn money. I never dared to spend all of the money I made because I had to spend half of my earnings on the plantation. I [also] had problems with the KNU when I started my plantation. Finally, I was allowed to cultivate the trees after I begged for permission. It would be like my life was over if the plantation was confiscated or destroyed. It is the thing I possess. It covers our house expenses and our children’s future school fees.”

One plantation owner asserted that, if his land growing more than 3,000 rubber and betel nut trees, coconuts, and citrus fruits was harmed in any way, he was willing to resort to armed protest with a revolutionary group. “I want to ask the government not to confiscate residential land, and to dispense grants for people to fully and unconditionally own their plantations.”

In some cases, plantation owners were not swayed by talk of compensation. “Our family’s future, healthcare, and children’s schooling will be destroyed if the plantation was confiscated or damaged,” said Nai Sein Aung, whose 6-person family also cares for three additional dependents. “Regardless of whether or not they will pay compensation, I do not want the plantation to be confiscated. We do not want to suffer from the authorities’ oppression. I want to tell them that we are fully aware of our rights and want them respected.”

Comments

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.