Monthly Overview: Destruction of Properties by the Military Junta Forces Thousands to Flee as the Displacement Crisis in Southeastern Burma Worsens

September 29, 2025

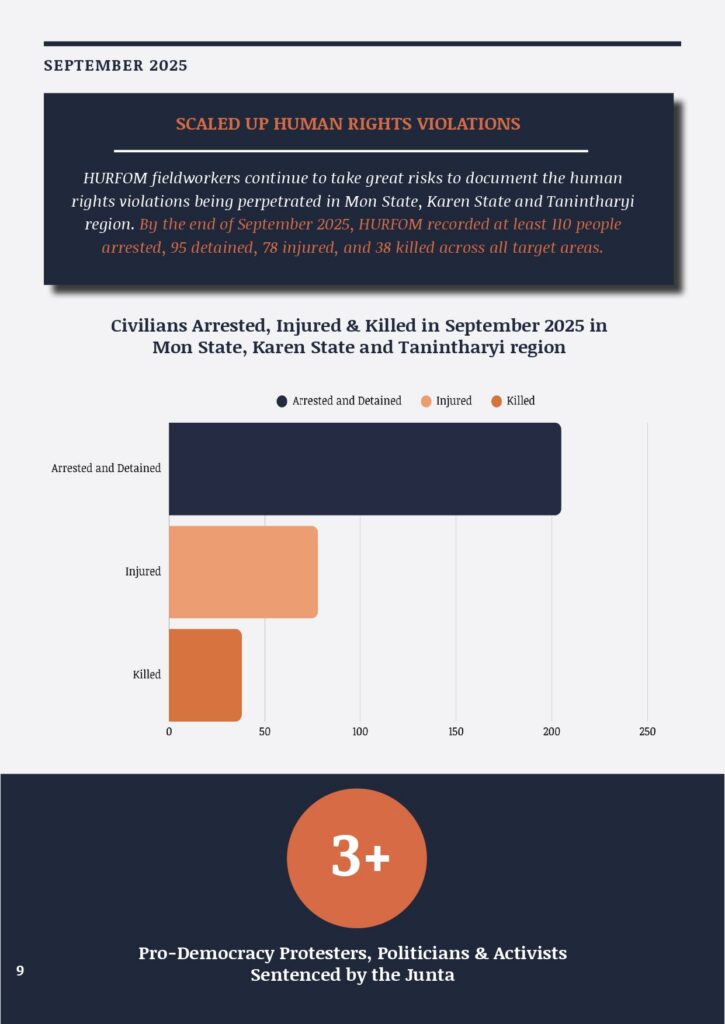

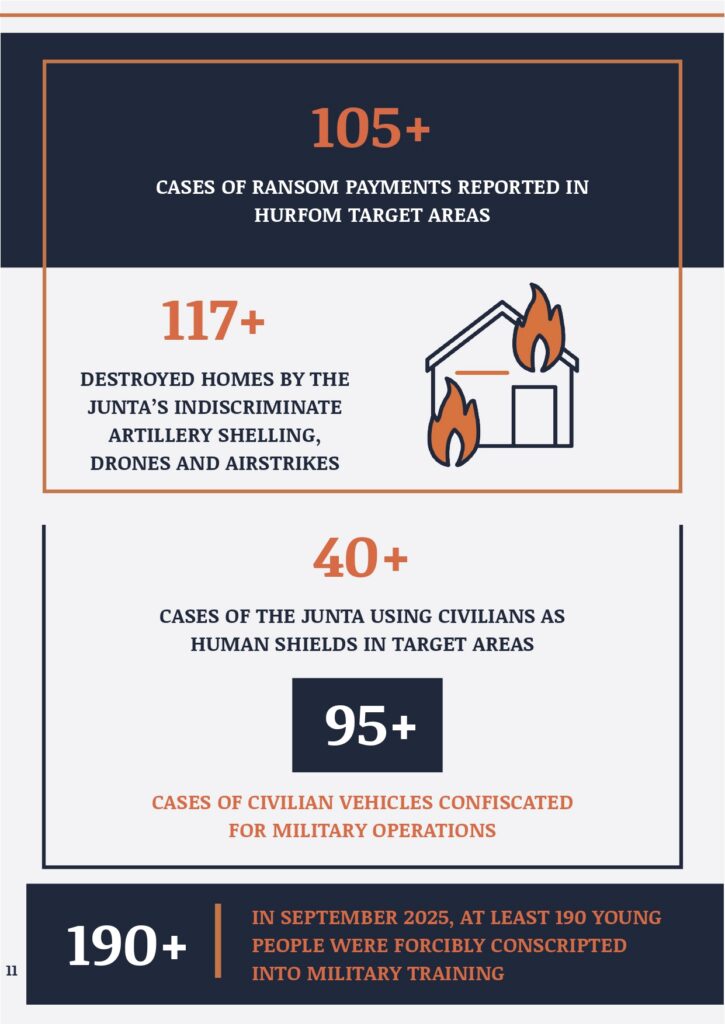

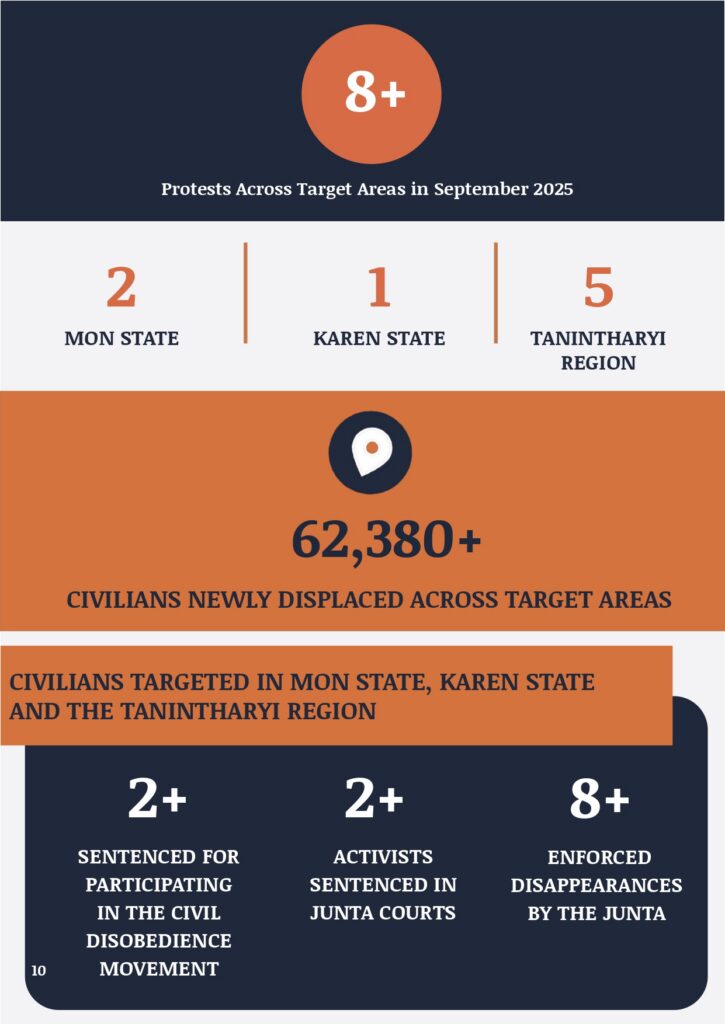

Throughout September, cases documented by the Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) revealed an alarming rise in fears and insecurities in communities across targeted areas of Mon State, Karen State, and the Tanintharyi Region. The junta’s ongoing attacks are worsening and thus contributing to continued concerns over livelihoods and survival. Children are not safe attending school as they are targeted in airstrikes. Doctors and nurses face ongoing threats to their lives and those of their patients, and mortar shells frequently target their clinics. Even sacred places of religious worship have been targeted in violent attacks. No one feels safe.

The ongoing presence and movement of junta troops through villages have left local communities living in constant uncertainty, with many forced to abandon their homes and seek safety elsewhere. Despite repeated displacement and loss, villagers continue to face harassment, arrests, and killings at the hands of junta troops. For many, even the simple act of trying to return home to collect belongings or feed animals has now become a life-threatening risk.

Continuous fighting in Yebyu Township has forced nearly 4,000 villagers from 10 villages to flee their homes, in urgent need of emergency assistance. From August 15 to August 28, clashes broke out almost daily near Mayan Chaung village between junta forces and allied resistance groups, including Mon, Karen, and Dawei revolutionary forces.

Due to the frequent artillery shelling by junta troops into civilian areas, thousands of residents were forced to escape. Villages affected include Kaw Hlaing, Mayan Chaung, Mile 60, Yar Phu, Thayar Mon, Alaesakan, Kywel Talin, Law Thine, Kyauk Ka Din, and Phayar Thone Su.

Displaced families are sheltering wherever they can. Many have taken refuge in relatives’ homes in Dawei town, Yebyu town, Kalein Aung town, Kanbauk village, and other parts of Yebyu Township. Others have fled further, towards Ye Township and Mawlamyine city, according to local sources.

The groups involved in the fighting include the Ramonnya Mon Army (RMA), Mon State Revolutionary Force (MSRF), Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) Battalion 27, Kyal Lin Yaung Liberation Army (KTLA), Strategic Operation Force (33), Dawna Battalion (2) (YGF), Dawna Battalion (KBDF), along with other allied resistance forces.

Since the third week of August, the junta has escalated its offensive with artillery shelling, drone strikes, and large troop deployments. Troops have advanced into many areas along Union Highway No. 8 between Kalein Aung town and Ma Hlwe Taung, triggering intense clashes and heightening risks for civilians. The situation remains dire, with displaced villagers facing shortages of food, shelter, and medical care.

Monasteries were also targeted and destroyed by a junta airstrike in Za Yat Seik village, Pulaw Township, Myeik District. Three buildings inside a Buddhist monastery compound were damaged after a fighter jet dropped bombs and fired machine guns.

At 1:10 PM on August 29, without any ongoing clashes in the area, a military aircraft bombed Za Yat Seik village. The monastery’s dining hall, kitchen, and another building were destroyed. While most of the population had already fled due to the conflict, only a few villagers remained in Za Yat Seik. No civilians were harmed in this particular attack. However, resistance groups reported that after launching airstrikes, junta forces have also been using drones to drop bombs and carrying out artillery shelling in the surrounding areas.

Fighting has continued near Pala town and nearby villages close to Za Yat Seik, forcing an estimated 5,000 people to flee their homes. The destruction of sacred places such as monasteries adds further trauma to communities already struggling with displacement and fear.

At least 25 displaced villagers who attempted to return to their homes in Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region, were arrested by junta forces on August 28. The arrests highlight the continuing dangers faced by internally displaced people (IDPs), even when they try to go back to their villages to gather food or care for livestock.

According to local sources, those detained included 15 villagers from Thar Yar Mon, seven from Mile-60, and three from Yar Phu Yaw Thit. Among the 25 arrested were five women. They were taken to the Yar Phu Yaw Thit monastery, which the junta has turned into a temporary holding site.

“There was no regiment in the villages when they fled. These villagers went back because they had been displaced for a long time. Some wanted to find food, others wanted to feed their livestock. They were arrested after encountering the regiment. Some were stopped at the entrance to Yar Phu Yaw Thit and taken with their motorbikes,” said one displaced villager.

The arrests come amid ongoing military tension and frequent clashes along the Ma Hlwe Taung–Ka Lane Aung section of the Union Highway No. 8. Since early August, more than 4,000 residents from at least six villages have fled due to heavy artillery shelling and ground offensives.

This is not the first incident. Just days earlier, on August 24, junta troops arrested 20 villagers, including a Buddhist monk. Although those detainees were eventually released on August 28, the arrests created fear and uncertainty among already traumatized communities.

Junta forces have also committed deadly acts of violence against civilians in the area. In Mile-60 village, soldiers shot and killed an elderly couple, both aged around 80, while their son remains missing. Such incidents underscore the ongoing pattern of crimes against local inhabitants, particularly IDPs who are left vulnerable after being forced from their homes.

Despite repeated displacement and loss, villagers continue to face harassment, arrests, and killings at the hands of junta troops. For many, even the simple act of trying to return home to collect belongings or feed animals has now become a life-threatening risk.

Arbitrary Arrest

Arbitrary arrests remain an ongoing concern as the junta continues to push forward with forced conscription. At least 25 men were arbitrarily detained overnight in Mawlamyine town, Mon State, as junta forces ramped up their enlistment efforts.

According to residents, on the night of August 26, junta troops, police, militia groups, and members of the so-called “people’s security and anti-terrorism team” carried out joint operations across the city. Within a single night, at least 28 men were taken away to be used as conscripts.

One of the most significant incidents occurred at 7:30 PM in Thiri Myaing Ward, where about 20 men leaving an alcohol shop were rounded up. “They waited outside to arrest those who were drunk coming out of the shop. They used good-quality private cars to carry out the arrests. It was unexpected. Around 20 men were taken,” explained a 40-year-old female eyewitness from the ward.

Similar arrests took place later that evening. At 8 PM, three local men who were looking at their phones outside No. (12) Basic Education High School in Myaing Tharyar Ward were seized and forced into private cars. At about 8:30 PM, a 55-year-old man from the same ward, who had just left a beer shop, was also abducted. “The 55-year-old man was arrested in the Mon compound of Myaing Tharyar Ward. He had been drinking at a beer shop nearby and was abducted when he left alone,” said a male resident who witnessed the incident.

Later the same night, a 21-year-old man, Maung Aung Pu, who lived on 13th Street in Myaing Tharyar Ward, was also taken by junta forces in a private car. Those arrested were reportedly transferred to Infantry Battalion No. 104 in Mawlamyine. According to a person close to ward administrators, instructions have already been given to prepare the detainees for transfer to military training camps.

Residents report that throughout the last week of August, junta forces in large numbers have been conducting sudden raids at night in busy areas, liquor shops, and other public spaces. People are seized without warning and driven away in private cars, deepening fear across the city.

A resident of Magin Ward, Kanbauk village tract, Yebyu Township, Dawei District, was also arrested at his home by Mawrawaddy Naval forces on the evening of 5 September and has not yet been released. The man was identified as Ko Aye Ko, a construction worker originally from Kanbauk village. Residents said the reason for his arrest remains unknown.

“At first, even his neighbours didn’t know he had been taken. When he disappeared, people started asking questions and then found out he had been arrested. He hasn’t been released yet, and the family has not been allowed to see him,” a Kanbauk villager explained.

Locals also reported that Mawrawaddy troops have been operating frequent security checkpoints in the Kanbauk area. “If you arrive near the gates, they order everyone to get out of the cars and motorbikes and continue on foot,” another resident said.

This incident follows earlier arrests on 20 August, when the naval forces detained six young men from Kanbauk and Taung Yin Inn villages under accusations of links to drug use. They were released about a week later, according to those close to the families.

Artillery Shelling

On September 8, the junta’s forces carried out an indiscriminate artillery attack on Yar Phu village, Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region, despite no armed clashes taking place nearby. The shelling killed a three-year-old girl and left a 40-year-old villager with severe injuries.

Troops from the regiment based in Ma Yan Chaung launched three artillery shells that landed in the middle of Yar Phu village. One shell struck a family home, instantly killing three-year-old Ma Ngwe Hmone Oo. Her grieving mother recalled the moment with anguish:

“It’s devastating to realize how wrong our decision was. Everyone else had left the village, but we stayed. Now I have lost my daughter. I feel like I’m going crazy without her.”

The family had initially migrated to Yar Phu from Mome Township in the Bago Region in search of work. The tragedy did not end with the child’s death. Later that evening, soldiers arrested her father, Ko Thura Aung, and as of this report, he remains in detention.

The artillery strike also gravely injured Ko Win Shwe, 40, when shrapnel tore through his lower leg, breaking the bone. Villagers explained how he had initially tried to flee, but returned to hide in his home after hearing reports of arrests outside the village. It was then that the shells began to fall. He is now receiving medical treatment at Ye General Hospital.

After the bombardment, the junta’s troops entered Yar Phu village and arrested at least eight more residents, further terrorizing a community already shaken by loss and fear.

This attack is yet another reminder of how the junta deliberately targets civilians. With no clashes in the area, the violence served no military purpose, only to destroy lives and instill terror in ordinary families.

Forced Conscription

The military junta has ordered wards and villages in Chaung Zone Township, Mon State, to send at least two conscripts for every round of military training. Local administrators, already struggling to meet these demands, have been forced to rely on costly substitutes to fill the quota.

According to local sources, hiring a substitute now costs between three and five million MMK. To cover this burden, administrators raised the so-called “conscription fee” to 10,000 MMK per household in August 2025.

“We used to pay 5,000 MMK. Since last month, they doubled it to 10,000 MMK. At a time when food and commodity prices are climbing, it’s impossible for families like ours. But if we don’t pay, we have to worry about our sons being taken,” explained a local woman.

In Mudon Township, residents face an even heavier burden, with households forced to pay 20,000 MMK each. “Every house must pay. No one dares to refuse. Even if we are struggling, we have no choice,” said a father from Mudon.

The junta’s administration teams have also informed local leaders in Mawlamyine, Mudon, Thanbyuzayat, and Paung Townships that each ward and village will be required to send at least two young men for every military training, further tightening pressure on communities.

Landmines

Two separate landmine explosions in late August and early September have left one child dead and at least three civilians seriously injured in Mayan Chaung village, Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region. The incidents highlight the growing dangers faced by civilians amid heightened military tensions along the Ye–Dawei road.

On the morning of September 1, a family of three travelling by motorcycle struck landmines near Mayan Chaung. U Ko Oo, in his 50s, and his wife, Daw Zar Chi Moe, in her 30s, sustained injuries, while their two-year-old son was killed instantly.

“They stepped on a landmine twice. The first one knocked down the motorcycle. As they tried to move away, a second one exploded. The child died on the spot. Ko Oo’s injuries are more serious, while his wife suffered lighter wounds,” a villager explained. Both parents were transferred to Dawei Hospital for urgent medical treatment.

Just two days earlier, on August 30, another villager, Ko Thein Htike Oo—also known as Ko Mon, a man in his 30s—was injured by a landmine in the same area while returning from Kalein Aung market. He lost vision in one eye and sustained a severe leg injury that required surgery and a bone implant.

The section of the Ye–Dawei road where Mayan Chaung is located, between Kalein Aung and Ma Hlwe Taung, has become heavily militarized. Junta troops and resistance forces have clashed repeatedly since August 27, forcing residents of at least ten nearby villages to flee. Locals report that trees have been deliberately felled to block the road, leaving civilians at greater risk of landmine explosions.

Due to the road closure, around ten passenger and cargo trucks from villages such as Loh Taing and Kyauk Kadin have been stranded, cutting off food and supplies.

“These are not battlefields—they are our homes and roads,” said one displaced villager. “Families are just trying to go to the market or return home to care for animals. Instead, they are losing their children, their eyesight, and their lives because landmines have been planted everywhere.”

The use of landmines by junta forces in civilian areas has become a widespread violation of international humanitarian law. Incidents like those in Mayan Chaung demonstrate the devastating human cost of the junta’s war tactics, with displaced communities caught between clashes, road closures, and indiscriminate violence.

Sham Election

In Mon State, the junta-appointed Chief Minister, U Aung Kyi Thein, has ordered officials to ensure that there are “no disturbances or obstacles” during the regime’s planned sham election in December 2025. His directive, issued on 4 September at a meeting in the Mawlamyine Government Office with state-level department staff, underscores how the junta is weaponizing security forces and militias to tighten control over communities.

Residents told HURFOM that militias and junta-backed “People’s Security Forces” are being armed and granted broader authority in the lead-up to the election. Rather than protecting the public, these groups act like thugs, roaming the streets drunk, extorting villagers, and intimidating youth. Their empowerment is linked to the Junta directive from February 2023, which allowed those deemed “loyal to the state” to carry firearms, including militia members, legally. As one local explained: “The policy is meant to reward loyalty. It hands guns to those who pledge allegiance to the regime.”

For ordinary people, this escalation has translated into growing fear and insecurity. Residents across Ye, Bilin, Thaton, and Kyaikmayaw Townships describe arbitrary checks, forced payments, and the constant threat of being detained by militia groups or military patrols. In some cases, young men are dragged into junta trucks at night or forced onto the frontlines as human shields. Families live under the shadow of enforced disappearances and fear of reprisals for refusing to cooperate with election preparations.

Analysts note that the junta’s militarization of daily life is tied to its electoral strategy. By expanding constituencies and asserting control in contested Mon and Karen areas, the regime hopes to stage elections in places where resistance forces and federal units already have legitimacy. A local researcher from Kyaikmayaw commented, “It is not about democracy. The election is just a tool to consolidate power. Giving weapons and privileges to militias increases repression while silencing civilians.”

These preparations mirror wider patterns across HURFOM’s target areas. Security has been ramped up at administrative offices and checkpoints, with harsher restrictions on movement. Residents describe extortion at roadblocks and raids that result in looting and confiscation of property. For many, the so-called “election security” feels like another form of occupation.

As a Mawlamyine resident put it: “Officials talk about safety, but the only thing we see is more fear. People are not interested in this election. They want to survive, not to vote.”

The junta has announced that elections in Mon State will be held in five townships: Kyaikto, Thaton, Mawlamyine, Chaungzon, and Kyaikmayaw, on December 28, 2025. Eleven political parties, including the USDP and Mon Unity Party, are expected to contest. Yet, with militias empowered, freedoms crushed, and people living in daily fear, these preparations reveal only the regime’s determination to cling to power, not the will of the people.

Local people in Mon State have also reported that so-called dalan (informers/collaborators), often operating with the junta-backed and armed Pyu Saw Htee militias, are becoming more abusive and exploitative of civilians. Acting as the Junta’s shadow police, these groups collaborate closely with soldiers and police, spying on neighbours, reporting “suspicious persons,” and using intimidation to control communities.

Residents say the problem has worsened since the Junta’s election commission instructed informers to immediately report any unfamiliar people in villages and wards ahead of the planned sham election. This order has emboldened them to act with greater impunity.

According to locals, informers are extorting large sums of money from traders, shopkeepers, and small businesses. Imported goods are seized under the pretext of being “illegal,” while restaurant and accommodation owners are pressured to pay bribes. Even ordinary villagers are targeted with arbitrary accusations of being suspicious to justify arrests.

A resident from Mudon described how the extortion now extends even to migrant workers:

“These informers have started demanding money from people preparing to go to Thailand for work. They ride around on motorbikes asking for payments. If goods come from the Thai side, people can’t cross at Sanpya Bridge anymore. They have to use rafts, and then when the cars pick up the goods, the informers demand money again. Now they are even extorting ordinary workers heading to Thailand.”

Reports from Mawlamyine tell a similar story:

“To put it bluntly, they are secret police or thugs. They have become more arrogant and are always looking for ways to cause trouble. The worst is when administrators or ward offices no longer resolve disputes in villages, but by these informers. Whoever can pay a bribe wins. Justice is gone. It is happening in many villages across Mon State. The junta is rewarding these groups with power because they want to ensure their sham election goes ahead.”

Residents also described how informers, sometimes accompanied by Pyu Saw Htee militias, stop motorbikes at junctions, check licenses, seize vehicles, and demand money. If anyone resists or even looks at them in the wrong way, they are beaten. Young people in particular are being targeted as “suspicious” and handed over to security forces.

Small business owners, including bars, restaurants, and karaoke shops, are being forced to make payments under various pretexts. Complaints about extortion go unanswered, and instead of taking action, local authorities side with the informers.

“Not only are they ignoring the abuses, but we also have to put up with their intimidation,” one villager said.

This system is not new. In Mon State, as well as in Karen and Tanintharyi Regions, the Junta has long relied on groups of informers, militia, and loyalists who function like a shadow police force. They are not official soldiers, but they act as the eyes and ears of the military. Villagers describe them as the junta’s “secret police” because of the way they operate in the shadows, instilling fear and mistrust in communities.

By using these collaborators, the military extends its reach into every ward and village, creating a climate of constant surveillance and intimidation. For ordinary people, the presence of these informers is a symbol of repression. They represent the brutal, hidden machinery of dictatorship — a system designed not to protect communities, but to control them, silence dissent, and enforce loyalty to an illegitimate regime.

In previous years, many informers were forced into hiding after local resistance groups carried out “dalan clearance” operations. But recently, residents say, they have resurfaced with renewed boldness. During the junta’s oversight in Mon State, more than a hundred informers have been eliminated, mostly in areas where resistance forces are active. Still, the fear of these collaborators remains strong, and their abuses continue unchecked, leaving ordinary civilians trapped in fear and exploitation.

Mon State

Residents continue to face unsafe lives as junta forces escalate their use of drones to target resistance checkpoints along civilian routes. On the afternoon of September 1, at around 4:00 PM, junta troops dropped at least four bombs from a drone over a resistance-operated checkpoint near Koh Doon village, Kyaikmayaw Township, Mon State, on the entrance road.

One civilian traveller was killed when a passenger vehicle was hit, and at least four others were injured. A private car was also damaged in the attack. An eyewitness who was driving nearby described the sudden strike on his social media:

“We were on the road near the junction between Koh Doon and Koh Panaw when the bombs fell. My car was badly damaged, but luckily, no one inside was hurt. The vehicle in front of me was not as fortunate—one passenger died instantly, and the car was destroyed. It was a matter of luck who survived.”

The injured were later transported to nearby hospitals with the support of local humanitarian volunteers. The drone attack has heightened fear among villagers and travellers. Local sources reported that resistance forces stationed near Koh Doon had recently conducted their own drone strike against a junta checkpoint, leading to increased security deployments by the military around the Sabe Gu Bridge and in surrounding areas.

A villager from Kyaikmayaw added:

“Since the resistance strike, the junta has reinforced its positions. At the Sabe Gu Bridge, there are more troops, and soldiers are even moving around disguised as civilians on boats. People know something more may happen, and we are all afraid.”

Residents are urging others to avoid unnecessary travel through this stretch of road, citing the unpredictable danger. The increased military presence near Pyar Taung Mountain has also raised concerns that further clashes could erupt, though no mass displacement has yet been reported.

Kyaikmayaw Township has a long history of clashes between junta forces and local resistance groups. In 2024, intensified fighting around Koh Doon and Koh Panaw villages displaced more than half the local population, with many families forced to relocate permanently to Mawlamyine or other urban areas. The latest drone attack underscores the ongoing insecurity that ordinary people in Mon State must live with, where routine travel can suddenly turn deadly.

For families already displaced by previous clashes, the fear of returning home remains overwhelming, as the threat of airstrikes, artillery shelling, and drone bombings continues to loom.

Residents of Mudon Town, Mon State, are living in fear after junta forces began arbitrarily arresting young men following the killing of a military informant by resistance fighters on September 1st. The incident triggered a sweeping security clampdown across Mudon, with soldiers setting up checkpoints on Kan Gyi and Chaung Hna Kwa roads and tightly controlling the entrances and exits of the town.

In the days that followed, many young men were seized without explanation. Locals worry that those arrested are being sent directly into the junta’s 16th batch of forced military training for conscripts. “We are terrified that our sons will be forced onto the frontlines as human shields. Once they are taken, they will not come back,” shared the mother of a 19-year-old who has been in hiding since the arrests began.

Residents explained that the junta has ordered each ward in Mudon to send two young men for every round of military training. Families who cannot provide recruits face immense pressure.

“It used to be possible to hire substitutes, but now even that is impossible. The junta has made young men their main target. Every night, soldiers and their militias roam the streets looking for someone to grab,” said a local father.

Each household in Mudon has also been forced to pay a monthly “conscript fee” of 20,000 MMK since early August, with desperate families paying up to five million MMK to hire substitutes. Yet even with these payments, many are still losing their sons. “We feel powerless. Even after paying, they can still take whoever they want. My husband and I stay awake at night, listening for footsteps outside. Our boy is only 18. If they catch him, he will be gone,” a parent said, her voice breaking.

Locals report that junta-backed militias and thugs, operating under the guise of “people’s security forces,” are assisting in the arrests and recruitment drive. These groups, often armed and emboldened, extort money, detain youths on the streets, and hand them over to the military in exchange for privileges. Their involvement has further deepened community fear: “They wear uniforms, but act like criminals. They know the names of our children. Parents are terrified even to let their sons leave the house,” said a villager from Mudon.

The campaign in Mudon reflects the junta’s nationwide desperation to fill its ranks following heavy battlefield losses. Instead of protecting communities, the so-called security forces have become predators, targeting innocent youth and turning their futures into bargaining chips for a failing regime.

Karen State

The Political Prisoners Network – Myanmar (PPNM) reported disturbing cases of torture and abuse inside Hpa-an Prison, Karen State, where 12 political prisoners were violently mistreated. One prisoner has died as a result of the abuse, while others remain in serious condition.

On June 14, the 12 political prisoners held in Kyo Kya ward were forcibly removed from their cells, beaten, shackled with leg-cuffs, and sentenced by prison authorities to three months of solitary confinement.

Among those targeted, Ko Zaw Win Aung (also known as Ko Jet Ko) was accused by prison officials of being a leader. For over a month, he endured daily beatings and punishments in the prison yard. The abuse caused him such severe psychological distress that he nearly attempted suicide, according to PPNM.

The brutality claimed the life of Ko Nyan Min Htun, who died on July 13 from injuries sustained under illegal torture and mistreatment. Other prisoners continue to suffer from physical wounds and psychological trauma. PPNM also confirmed, with evidence, that a senior prison official, Aung Ye Naing, threatened to kill the 12 prisoners if news of the torture was leaked outside.

In response, PPNM is demanding urgent action:

- The immediate release of the 12 political prisoners from leg cuffs and solitary confinement.

- Access to medical treatment, including psychological support.

- Assistance to address the long-term impacts of torture and trauma.

The deaths and suffering in Hpa-an Prison are part of the junta’s broader campaign of cruelty against those who dare to resist its illegitimate rule.

On September 13, 2025, the junta launched indiscriminate artillery attacks on Than Pa Yar village, Kyarinnseikyi Township, Karen State. The shelling killed 50-year-old U Win Aung, who was fishing in a nearby stream. His body was discovered by villagers the following morning.

The attacks also left others injured and damaged homes, prompting residents from Than Pa Yar and surrounding villages to flee in fear.

“The situation is terrible. Everyone has run away. It’s not only our village—people from nearby areas have also fled. We come back in the daytime to check our homes, but no one dares to sleep there at night. The army keeps firing artillery, and people are being hurt,” said a local villager.

Since early September, the junta has reinforced its troops near Chaung Hna Kwa village, Kyikemayaw Township, Mon State, and has been targeting villages along the Za Mi River. The artillery strikes have left hundreds of families displaced.

Those who fled are now taking shelter in villages on the opposite side of the river, but they urgently need food, safe shelter, and support to survive.

Tanintharyi Region

Junta troops began advancing through villages in the Nabule area of Yebyu Township, Dawei District, forcing residents to flee their homes on the morning of August 29. According to displaced villagers, soldiers from the temporary military base at the Dawei Special Economic Zone and deep-sea port began moving through Htein Kyi, Lae Shaung, and Paradat villages at 6 AM.

“They came to Htein Kyi first, then went to Lae Shaung monastery, and now they’re in Paradat village. Villagers have already run away. We don’t know yet whether they have arrested anyone,” a local woman explained.

Reports indicate that at 5 AM on the same morning, the column joined forces with another unit advancing from Nan Thar Ai village before entering Paradat. This follows earlier troop movements in the same area. On August 26, a column of about 100 soldiers stationed themselves inside the school and local homes in Mu Du village, which also forced residents to flee in fear of arrest and violence.

In a separate case, at least 25 displaced villagers who attempted to return to their homes in Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region, were arrested by junta forces on August 28. The arrests highlight the continuing dangers faced by internally displaced people (IDPs), even when they try to go back to their villages to gather food or care for livestock.

According to local sources, those detained included 15 villagers from Thar Yar Mon, seven from Mile-60, and three from Yar Phu Yaw Thit. Among the 25 arrested were five women. They were taken to the Yar Phu Yaw Thit monastery, which the junta has turned into a temporary holding site.

“There was no regiment in the villages when they fled. These villagers went back because they had been displaced for a long time. Some wanted to find food, others wanted to feed their livestock. They were arrested after encountering the regiment. Some were stopped at the entrance to Yar Phu Yaw Thit and taken with their motorbikes,” said one displaced villager.

The arrests come amid ongoing military tension and frequent clashes along the Ma Hlwe Taung–Ka Lane Aung section of the Union Highway No. 8. Since early August, more than 4,000 residents from at least six villages have fled due to heavy artillery shelling and ground offensives.

Just days earlier, on August 24, junta troops arrested 20 villagers, including a Buddhist monk. Although those detainees were eventually released on August 28, the arrests created fear and uncertainty among already traumatized communities.

Junta forces have also committed deadly acts of violence against civilians in the area. In Mile-60 village, soldiers shot and killed an elderly couple, both aged around 80, while their son remains missing. Such incidents underscore the ongoing pattern of crimes against local inhabitants, particularly IDPs who are left vulnerable after being forced from their homes.

Fear and devastation spread through Yan Taung and Thin Kyun villages in Thayet Chaung Township, Dawei District, after junta troops torched dozens of homes on the morning of September 7.

At around 9:30 AM, over 100 soldiers moved into the area from their base near Moe Shwe Kone village. Residents said the troops set fire to houses in Yan Taung and Thin Kyun shortly after being ambushed by resistance forces while travelling in passenger vehicles.

“They burnt down houses with and without people inside. In one case, they called out to someone hiding inside. When the person didn’t come out, they set the house on fire with him still inside,” a villager told HURFOM.

At least 25 homes were destroyed in Yan Taung and another 8 in Thin Kyun. Among the ruins are two-story family houses, modest wooden dwellings, and small shelters that villagers had built with their savings.

After the arson attacks, troops continued toward Thayet Hnit Kwa village, where they are stationed. This latest assault follows an earlier round of raids in late August, when soldiers burned around 70 houses and killed two villagers in Saw Phyar, Moe Shwe Kone, and Uttu villages. The repeated destruction has left hundreds displaced, with families scattered in nearby forests and monasteries, unable to return.

A local woman said, “It is not only the houses that are gone. Our hopes and our safety are destroyed with them. Each time they come, we wonder if our family will survive.”

Then, in Taung Yin Inn village, Yebyu Township, Dawei District, junta soldiers stationed near Phar Chaung village tract have left a trail of devastation. Between August 24 and September 2, the troops torched homes and carried out arbitrary arrests.

Residents said the soldiers set fire to about 18 houses in the center of the village. “A total of around 18 homes were destroyed. Ten of them were completely reduced to ashes. They even poured sand into the engines of motorcycles hidden in the monastery. It seemed like they wanted to destroy everything they could,” explained one villager.

After burning the homes, the troops withdrew, but not before seizing two men in their 50s who were trapped inside the village, along with others they encountered along the road. As of September 8, none of the detainees had been released. The fear of further attacks has forced many families in the Phar Chaung area into a routine of displacement. Villagers return to their homes during the day to salvage what they can, but at night they flee and sleep elsewhere for safety.

Within just ten days of the junta’s arrival in the Phar Chaung tract, at least six clashes have erupted between regime forces and local resistance groups. Resistance members report junta casualties, though both sides have suffered losses in the fighting.

In Taung Yin Inn village, Yebyu Township, Dawei District, junta troops who had temporarily stationed in the area have threatened to shoot residents attempting to return to their homes. Advancing from Phar Chaung village tract, the soldiers set fire to around 18 houses in Taung Yin Inn between 24 August and 2 September.

After torching the homes, the troops initially withdrew but returned in early September. When villagers tried to come back, they were forcibly expelled and warned they would be killed if they stayed.

“The troops are driving out anyone who returns. They threaten to kill those who go back, and they destroyed everything. No one dares to stay now,” a resident told HURFOM.

It remains unclear whether the soldiers are still present, but displaced families say that some villagers from Phar Chaung only risk returning during the daytime. At the same time, at night, they hide elsewhere for safety.

During the occupation, junta troops arrested two men in their 50s from Taung Yin Inn, along with other residents encountered on the road. As of 8 September, none of them had been released. The situation in the Phar Chaung tract has grown increasingly volatile. In just ten days, at least six clashes erupted between junta forces and local resistance groups. While resistance groups reported junta casualties, both sides are believed to have suffered losses.

Since August 2025, the junta has reinforced its troops and launched a significant military advance in Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region, sparking heavy and ongoing clashes with joint revolutionary forces. In addition to ground fighting, the army has fired indiscriminate artillery into residential areas, forcing thousands of civilians to flee.

As a result, schools across Yebyu have been forced to close. Villages including Kywe Ta Lin, Ma Yan Chaung, Thar Yar Mon, Ye Bu Yaw Thit, Yar Phu, Ywell Tie, Kyauk Ka Din, Ah Lell Sa Khan, Pha Yar Tone Zu, and Sein Bone remain tense with fighting, making it impossible for children to attend classes.

“Most children can’t go to school. If the situation becomes stable, every student will return home and resume their studies at school. But right now, clashes are still happening. No one dares to go back,” explained one parent from Yebyu Township.

Displaced families are also struggling with the costs of education outside their villages. “We have to rent a house here, and it is costly. We cannot afford the school fees. If things become stable, we will go back home. For now, my child has had to stop their studies,” said a displaced mother.

The conflict in Yebyu has not only denied children their right to education but has also left displaced communities facing severe food shortages as the fighting drags on with no end in sight.

Destruction of properties, including religious monuments, also continues to pose serious risks to civilians. On September 14, Yak Kansin Monastery in Pakari village, Dawei Township, Tanintharyi Region, was struck by an aerial bomb. The blast damaged the monastery building and destroyed several nearby houses. Local residents explained that the attack followed clashes when allied People’s Defence Forces launched an assault on junta troops stationed at the Pakari police camp and inside the monastery compound. During the fighting, two villagers from Pakari were killed.

The next morning, September 15, the junta launched further airstrikes on the monastery, while also firing machine guns from the air. As a result, the remaining monastery buildings were completely destroyed, and additional homes in the area were badly damaged.

By September 17, junta forces escalated their attacks, using Y-12 aircraft to carry out multiple bombings around Pakari village. Residents reported that bombs were dropped at least twice in the morning, forcing families to flee once again. According to the KNU’s Myeik–Dawei District office, the clashes left 10 junta soldiers dead and nearly 15 wounded, with weapons and ammunition seized by resistance fighters.

That same day, two Y-12 aircraft extended the bombing campaign across Dawei District, targeting Dawei, Launglon, Thayet Chaung, and Yebyu townships. Heavy bombardments sent villagers running in fear, as bombs fell more than twice in some areas.

“People are running in every direction. Monasteries and homes have been destroyed, and we don’t know where is safe anymore,” said one villager who fled with his family

On September 6, 2025, troops from a junta regiment advanced into Yar Phu and Kywe Ta Lin villages in Yebyu Township, Tanintharyi Region, and carried out operations that lasted for several days. The soldiers eventually withdrew from Yar Phu on September 12, moving toward Ka Lane Aung Town and Ma Yan Chaung village.

After the retreat, villagers discovered the bodies of two young men in Kwat Thit Ward, Yar Phu village. The victims were brothers, aged 17 and 25, who had been fatally shot.

“On the day the regiment entered the village, there was gunfire. The two brothers had first taken their grandfather to a displaced persons camp and then went back home. After that, no one heard from them again,” explained a Yebyu resident.

Villagers believe the brothers were killed on their way back to their house. Their bodies were cremated on September 15.

“There were also reports of a woman who was killed and beheaded, but so far we have only been able to confirm the two brothers’ deaths,” another resident said.

During the junta’s occupation, soldiers looted many of the empty homes left behind by displaced families. At least ten villagers were also arrested.

Residents in Thayet Chaung Township, Dawei District, Tanintharyi Region, reported that Junta forces have reinforced their presence with more than 250 troops. Since mid-September, these forces have carried out a wave of destruction, burning homes, looting property, and forcing villagers to flee in fear.

On September 20, junta troops re-entered Yan Taung village and set fire to homes that displaced families had already abandoned. Residents told HURFOM that the soldiers threatened to burn any houses left empty, deepening fear in the community. This latest violence comes after earlier operations in the first week of September, when junta forces attacked resistance groups near Yan Taung. In retaliation, they torched 34 houses in Yan Taung and nine in Thin Kyun village, destroying a total of 43 homes. Some of these houses belonged to families already displaced, while others were burned while residents were still inside. Survivors now live in makeshift bamboo huts erected beside the ashes of their destroyed homes.

A local villager explained:

“There are about 250 troops stationed in Yan Taung now. They said if a house is found empty, they will burn it. People are terrified. Last time, they even burned houses where people were still inside.”

Junta violence has also extended across Thayet Chaung, Launglon, and Dawei Townships. On September 17, at least ten villages in these areas were hit by aerial bombardments, leaving civilians injured and killed. The destruction has forced thousands more to flee, adding to the already overwhelming number of displaced people.

According to FE5 Tanintharyi, more than 18,000 civilian homes in Tanintharyi Region have been burned since the military’s attempted coup in 2021. HURFOM fieldworkers have documented repeated cases in Dawei District and Thayet Chaung where families are left with no shelter, forced to rebuild temporary huts from bamboo and tarpaulin with little or no aid.

The scale of displacement in Tanintharyi is worsening. By August 2025, local research teams estimated that over 82,000 people had been displaced across the region. With Junta reinforcements escalating attacks, communities in Dawei District remain at constant risk, facing daily threats to their homes, safety, and survival.

Feature

Junta-backed militants target communities with fear and attacks ahead of the sham election.

In Mawlamyine, Mon State, junta-backed militias under the banner of “People’s Security Forces” and allied groups are increasingly behaving like criminal gangs. Instead of providing protection, they have been abusing power, harassing locals, and spreading fear.

Residents report that these groups roam the streets and villages in large numbers, often drunk, extorting money, and even dealing in narcotics. They randomly detain people, seize motorbikes, and conduct intimidation campaigns. “They wear blue uniforms and act like thugs. If they see you at the wrong time or place, they drag you off, question you, or sometimes make you disappear,” said one young resident.

Local youths are also being lured into these militias with false promises that they will avoid frontline conscription if they join. Recruits are told they can remain in their villages, enjoy privileges, and even take part in drug use without punishment.

A villager noted: “They tell young people: join us, and you won’t be sent to fight. You can stay home and do whatever you like. But once you join, they control you.”

“One day, I was just walking at 6:30 AM, and they seized every motorbike on the road. Another day, they rounded us up at 4 AM on the street,” one young resident shared. “They drag people off by name, or call them in if they cross paths. It’s random, it’s frightening. They act like a force, but in reality, they scare everyone like thugs.”

Authorities tied to these militias sometimes release those close to them—village administrators or friendly officials—after extorting money. Others are taken away without a word. This unchecked abuse of power is leaving communities shattered.

“In villages where these forces barge through, they stop daily life: they check guest lists, stop celebrations, even guard tiny events. It’s as if they run the town, not us,” another villager said.

Those with connections to ward administrators or junta-aligned figures are sometimes released after paying bribes, but others remain unaccounted for. “If you know someone, you can pay and be freed. If not, you just disappear,” another resident explained.

This lawless behaviour is part of a broader strategy. On August 30, 2025, the junta secretly announced the formation of a new nationwide committee tasked with training, arming, and supplying militias at the ward and village levels. Signed by General Aung Lin Dwe, the Junta’s secretary, the order places control of these groups under the Ministry of Border Affairs, with vice-chair roles assigned to the Deputy Defence Minister and the Deputy Home Affairs Minister, and seats for the Police Chief and military department heads.

According to the directive, the panel will arrange the supply of food, arms, and training, provide logistical support for military operations, and oversee recruitment and personnel management. It will even compensate families of militia members killed or wounded and recruit technicians for advanced weapons. In return, recruits can receive deferments or exemptions from conscription.

This escalation comes two weeks after the junta lost Northeastern Command in Shan State and six months after it announced mandatory military service. With military casualties surging and recruitment collapsing, the Junta is turning civilians into armed enforcers.

Human rights monitors warn that these militias are becoming indistinguishable from thugs. They operate with total impunity, looting homes, shaking down residents, and abusing power in daily life.

“These groups are supposed to keep order, but they act like criminals,” a villager from Mawlamyine said. “Now people are even afraid to pass through their checkpoints.”

The pattern mirrors wider repression across southern Burma. In Tanintharyi Region, HURFOM field teams documented a sharp rise in violence, with airstrikes tripling in July 2025 compared to June, and over 82,800 civilians displaced by late August. This combination of armed militias on the ground and relentless aerial bombardment from above has left people in Mon and Tanintharyi regions living in constant fear.

As the military pushes ahead with its planned sham election, these militias, armed and unleashed under the guise of “people’s security”, are functioning as instruments of intimidation and repression, silencing communities and tightening the military’s grip on power.