Monthly Overview: Four Years Since the Attempted Coup in Burma Marks an Ongoing Downfall of Rights & Freedoms

February 3, 2025

HURFOM January 2024

Four years have now passed since the attempted coup in Burma on 1 February 2021. The Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) has worked tirelessly to document the worrying escalation of violations. We have utilized established human rights defenders (HRDs) networks, trusted documentation teams, and well-trained personnel.

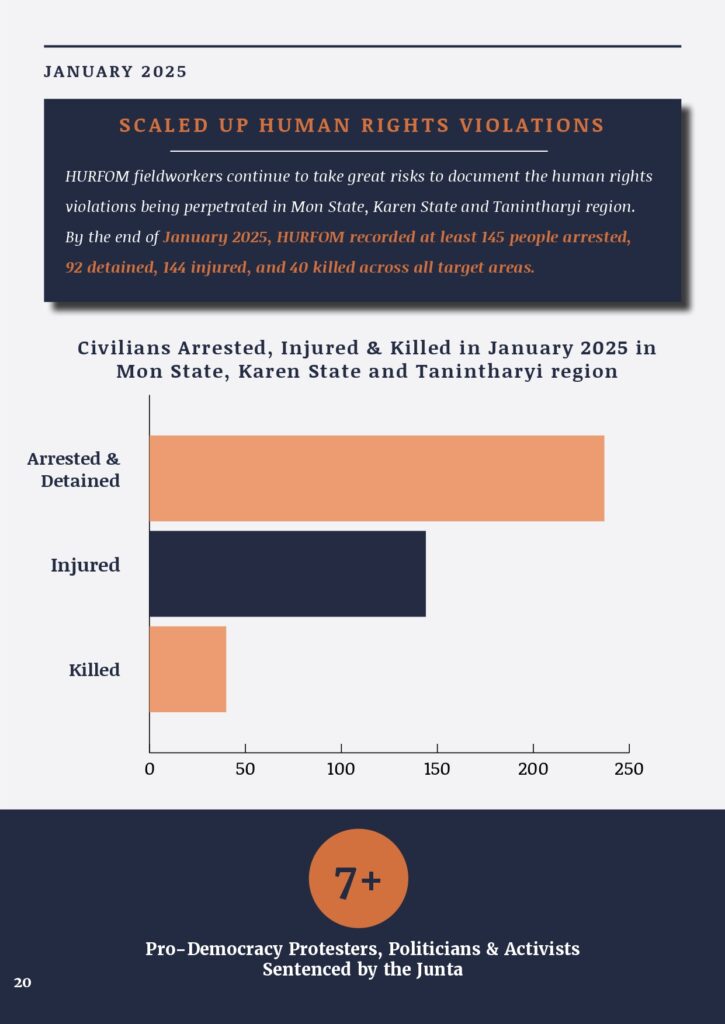

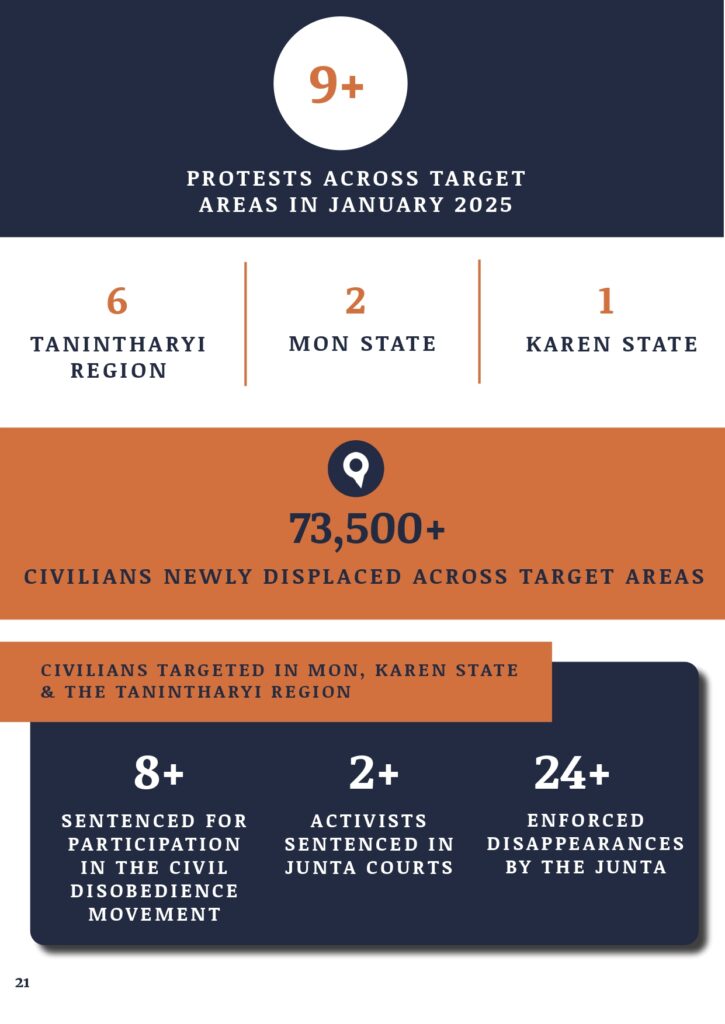

The ongoing conflict in southeastern Burma has led to severe human rights abuses, with widespread violence directed at civilians. The last year ended with an increase in forced displacement and a worsening humanitarian crisis, which has led to millions displaced. In HURFOM target areas of Mon State, Karen State and the Tanintharyi region, there were at least 63,000 forced to flee their homes in December 2024. This month, that number increased to 73,500.

There are life-threatening shortages in preventive treatment and care, especially for young children and expectant mothers. Educational prospects for many have been forcibly put on hold. Livelihood opportunities are virtually non-existent, particularly in rural areas. Families have suffered innumerable losses as the struggle to survive is one of endless anxiety about the future.

HURFOM reaffirms our commitment to ensuring the world knows what is happening in Burma and what actions are vital for ensuring there is an immediate end to the crimes perpetrated against innocent civilians. This includes advocating for the junta’s sham election planned for later this year to be condemned and not legitimized by any international recognition.

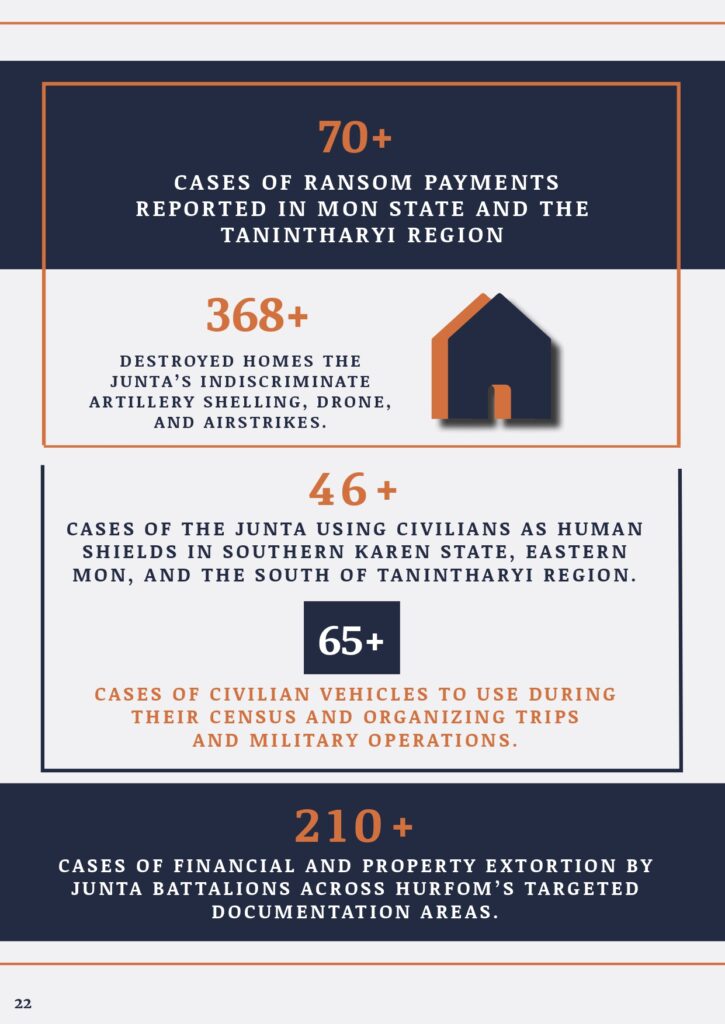

In preparation for the upcoming sham elections, the military junta has been conducting a systematic census throughout the states and regions. This process suppresses the rights of ethnic minorities and restricts political freedoms, further reinforcing the junta’s grip on power. Additionally, the junta’s increased militarization has led to the formation of militia forces, granting them privileges and empowering allied groups to strengthen their control over villages. As a result, there are more threats to personal safety, severe restrictions on livelihoods and travel, and widespread property extortion.

The military has also attempted to appease the international community through its political prisoner amnesties, which are also misleading, lack transparency and, above all, serve as a reminder that no one should be imprisoned for exercising their fundamental rights and freedoms. In its most recent release of political prisoners, the junta inflated the numbers.

In Mon State alone, 254 prisoners were reportedly granted amnesty. However, according to reports, only six political prisoners were included—five from Kyaikmayaw Prison and one from Thaton Prison.

As part of its 77th Independence Day commemorations, the junta claimed to have released 5,864 detainees nationwide. Among them, the junta spokesperson, Major General Zaw Min Tun, stated that over 600 were detained under Section 505 of the Penal Code, commonly used to imprison political dissidents. However, according to the Political Prisoners Network of Myanmar (PPNM), only about half of that number were actually released.

“Our records show a significant gap between the junta’s announcements and the actual numbers of political prisoners released. It’s mostly propaganda. According to our verified list, Thaton Prison only released one political prisoner, while Kyaikmaraw Prison released five,” explained Ko Thike Tun Oo of PPNM.

The amnesty from Kyaikmayaw Central Prison included 12 male and two female detainees. Only three men and two women prisoners had been convicted under Section 505.

The released detainees across Mon State were as follows:

- Kyaikmayaw Central Prison: 14 detainees, including five political prisoners

- Thaton Prison: 36 detainees, including one political prisoner

- Yin Nyein Labor Camp: 26 detainees

- Zinkyaik Labor Camp: 18 detainees

- Inn Byone Labor Camp: 8 detainees

- Moppalin Men’s Factory Camp: 37 detainees

- Moppalin Women’s Factory Camp: 43 detainees

- In Gya Bo Rubber Plantation Camp (Shwe Phyu): 8 detainees

- Despite the junta’s publicized claims, many see these releases as an attempt to improve its international image without making meaningful concessions. The number of political prisoners freed remains disproportionately low compared to the thousands who continue to be unjustly imprisoned across the country.

Further, the situation in Burma remains precarious, with the potential for further deterioration as the junta continues its efforts to consolidate power through force and repression. Continued documentation and advocacy are essential to keep the international community informed and engaged in addressing the ongoing crisis. Transitional justice initiatives, including criminal justice, truth-seeking, reparations for victims and survivors, and supporting future institutional reform, are urgently needed in Burma to prevent such atrocities from recurring.

These calls for action are further evidenced by this latest monthly report from HURFOM, which shows civilians continuing to confront harrowing realities across our respective target areas. The junta is ruthlessly deploying airstrikes to target and assault innocent civilians, fuelling the worsening humanitarian crisis. Heavy artillery and the firing of mortar shells also contribute to grave losses of life. Freedom of expression and the right to information are being violently suppressed as the junta continues to weaponize the rule of law for its own strategic purposes.

On January 1st, the junta officially enacted Cybersecurity Law No. 1/2025 under Article 419 of the Constitution. The law comprises 16 chapters and 88 articles and outlines severe penalties for unauthorized VPN use and various online offences, including fines and imprisonment.

The law mandates penalties of up to six months in prison and fines of up to 2 million kyats for those caught using VPNs without approval. It also includes penalties for cybercrimes such as online fraud, illegal gambling, and unauthorized financial transactions, with prison sentences ranging from two to seven years and significant fines.

The junta claims the law aims to protect national stability and authority by preventing cyberattacks and ensuring control over digital spaces. However, local legal experts and rights groups have raised concerns that the law primarily targets free expression and access to information.

A legal expert from Mawlamyine commented:

“The VPN law is being misused to control public narratives. The Junta is more interested in restricting independent information flow rather than focusing solely on legitimate cybersecurity concerns.”

The law includes provisions for confiscating devices and materials used in alleged cybercrimes as state property, adding another layer of control.

Since the military coup in 2021, millions of Burmese citizens have relied on VPNs to access social media platforms like Facebook, which the junta has blocked. In late 2024, the junta escalated its crackdown by deploying Secure Web Gateway (SWG) technologies, reportedly with support from Chinese tech firms, to strengthen digital surveillance and block VPN access. Despite this, many residents continue to use VPNs, risking searches and extortion at security checkpoints.

Nai Aue Mon, Program Director of the Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM), provided his perspective on the junta’s cybersecurity policies:

“Since the coup, the military has tried to exert total control over cyberspace by introducing policies, drafting legal frameworks, and increasing surveillance. They’ve aimed to directly monitor internet service providers and extract data from news agencies and businesses reliant on online communication.

While the law claims to target cybercrimes and illegal online activities, its real intention is to suppress free speech, restrict access to independent news, and isolate the public from the international community. People have been forced to rely on VPNs due to successive information blackouts. The Junta’s response has been arbitrary arrests, extortion, and lengthy prison sentences, all of which violate fundamental human rights.”

Nai Aue Mon highlighted that in free and democratic nations, cybersecurity laws are designed to protect citizens’ rights rather than curtail them:

“In free countries, cybersecurity regulations ensure the right to information, freedom of expression, and digital safety. These laws protect the public, not oppress them. The junta’s cybersecurity law, however, is a deliberate attempt to sever the people’s connection to the world and hide their atrocities—such as indiscriminate airstrikes and the use of advanced weaponry against civilians from global scrutiny.

The United Nations Human Rights Council has repeatedly condemned laws that excessively restrict online freedoms and called for repealing oppressive regulations. By enforcing such laws, the Junta is committing further human rights violations. Access to the Internet and the ability to share information are essential rights, especially when these same digital channels are vital for the public to report ongoing military violence and crimes.

This cybersecurity law isn’t about public safety—it’s a tool of fear designed to prolong the Junta’s grip on power by silencing dissent and controlling communication.”

Nai Aue Mon emphasized that the law directly threatens freedom of speech and could further isolate Myanmar from international dialogue. He concluded by saying:

“It is crucial to have timely access to information to protect civilians from the junta’s relentless assaults, including daily airstrikes, indiscriminate artillery fire, and drone attacks. By severing communication channels and isolating the country from global awareness, the Junta is committing war crimes in plain sight. This new law aims to suppress access to information and communication further, signalling a deliberate attempt to pave the way for even more severe human rights violations and war crimes.”

Arbitrary Arrests

Four fishermen, all in their 30s, were arrested at a junta checkpoint in Set Taw Yar village, Pulaw Township, Myeik District, on January 5 at 11 AM. They were accused of being members of the People’s Defense Force (PDF). The men were travelling in a passenger vehicle from Dawei to Myeik in search of work in the fishing industry.

“The junta likely did this to recruit more soldiers. The fishermen were beaten at the checkpoint before being taken away,” shared a male eyewitness from the area.

The arrested men are reportedly from Dawei District, as they spoke with the distinct Dawei dialect. However, locals were unable to confirm their exact identities.

Junta troops have been stationed in the monastery compound in Set Taw Yar village, and reports suggest the four fishermen are being held in the soldiers’ occupied buildings. However, no official confirmation has been made regarding their whereabouts. The Set Taw Yar checkpoint was established after the junta launched a military offensive in the village in mid-October 2023.

In December 2023, the junta detained around 179 civilians across eight townships in the region. Additionally, approximately 219 civilians—some deported from Thailand—were forcibly conscripted into military service at Kawthoung port.

From the night of January 6 to January 9, junta troops conducted checks in Yan Gyi Aung, Yan Myo Aung, Aung Metta, Aung Mingalar, and Chaung Taung wards of Ye town. According to residents, around 10 local men were arrested during these operations.

“When they found houses locked, the soldiers shouted for the doors to be opened. If no one responded, they broke the doors down,” said one resident.

The inspections involved checking ID cards and household records. Soldiers claimed they were investigating non-locals, but some residents were also taken away and have not yet been released.

A woman from Ye shared that the troops arrested Ko Zaw Min Oo, a man in his 40s from Aung Mingalar ward, along with three other men in their 30s from Aung Metta ward, and took them to the Ye police station.

The arrests were made without notifying the ward administrators. Residents reported that soldiers entered neighbourhoods in five vehicles, inspecting homes and reviewing guest registration records.

“They checked everything—ID cards, household records, and even looked through homes for anyone unregistered,” a resident said.

With over 40 troops involved, the junta reportedly detained individuals they suspected of having ties to resistance groups. Some were fined, while others were handed over to the police. The exact number of those detained and the reasons for their arrests remain unclear. Local sources are still working to confirm the names and details of the detainees.

In December, at least 10 residents of Ye were detained during similar guest registration checks on accusations of connections to the People’s Defense Forces. These ongoing inspections have heightened fear and anxiety among locals, many of whom now worry about their safety and the possibility of further arbitrary arrests.

On the night of December 28, the military junta raided homes under the pretense of guest list inspections and arrested five young women in Thaton Township, Mon State. Local sources report that the women were forcibly taken to a military training camp, a disturbing escalation in the regime’s conscription practices.

The arrests occurred in Bin Hlaing and Nan Khae neighbourhoods. Two women were detained in Bin Hlaing on December 28, and three more were detained in Nan Khae on December 26. All five were reportedly sent to Military Training Camp No. 9 in Thaton Township. A local military observer confirmed their location but noted that the families of the detained women have refrained from speaking out publicly due to serious security concerns.

“This is the first time in Thaton that young women have been taken to a military training camp,” a resident shared. “In the past, forced conscription targeted young men, but now there are rumours that women are also being targeted.”

The women, aged between 20 and 25, were arrested late at night under the guise of checking guest registrations. Residents report that junta soldiers searched their phones and used findings of politically sensitive content as justification for the arrests.

“They were interrogating the women for anything related to politics. That’s what they claimed when they took their phones,” said a resident of Bin Hlaing.

The crackdown in Thaton Township was not limited to women. On the night of December 26, 13 young men from the Nan Khae neighbourhood were also detained during similar guest list inspections and sent to Training Camp No. 9.

Three men from Ta Po village in Pulaw Township, Myeik District, Tanintharyi Region, remain in detention four days after being arrested by junta troops. On January 11, junta forces entered the village and detained U Tin Soe (53), U Kyi Soe (45), and U Myo Htike Oo (42). The following day, the men were reportedly transported by water to Myeik, but this information has yet to be officially confirmed. Junta troops in the Pulaw area are known for detaining villagers and using water routes to transfer them to Myeik.

Adding to the devastation, on the same day as the arrests, junta troops burned down five houses and several rubber plantations located between Ta Po and Set Taw villages. The fire spread rapidly and continued to consume the western mountainous areas of Set Taw village as of January 16.

This is not an isolated incident. In December 2023, junta troops conducting operations across nine townships arrested more than 300 civilians. The plight of the three detained men and the destruction of homes and livelihoods in Ta Po village highlight the ongoing suffering endured by civilians under the junta’s oppressive actions.

Artillery Attacks

A 24-year-old woman was injured after junta troops launched an unprovoked artillery attack on Wa Duk Kwin village in Thein Zayat Town, Kyaik Hto Township, Mon State, despite no active clashes in the area, according to local sources.

The incident occurred in the early hours of Independence Day, January 4, at around 4 a.m., when the 310th Artillery Battalion, stationed in Thein Zayat, fired more than seven artillery shells without any apparent provocation. One of the shells struck Wa Duk Kwin village, injuring a young woman named Ma Kyan, who sustained wounds to her hand and body from shrapnel.

“An artillery shell was fired early in the morning. A woman was hit. She is now receiving treatment at Thein Zayat Hospital,” a resident from the village shared.

Wa Duk Kwin is home to a community of migrant workers and lies within the Karen National Union (KNU) Brigade 1, Thaton District-controlled area.

This attack comes after a similar incident on December 26, when a 20-year-old woman named Ma Aye Thandar was severely injured in the same village due to junta artillery strikes. She, too, is currently being treated at Thein Zayat Hospital for multiple injuries across her body. According to KNU reports from Thaton District, junta artillery shelling in villages under their control resulted in four civilian deaths and injuries to five others in December alone.

The targeting of innocent civilians during unprovoked attacks continues to cause devastation in Mon State, further illustrating the junta’s blatant disregard for human life. Local communities remain gripped by fear as these assaults persist without warning or justification.

In a separate case, two civilians, including a 13-year-old girl, were injured by artillery shelling from junta forces in Inn Pyar village, Kalain Aung Sub-Township, Yebyu Township, Dawei District. The incident occurred on the evening of January 5, at 6 PM, when Artillery Battalion 408, stationed near Kalain Aung town, launched a continuous artillery attack. One shell exploded in Inn Pyar village, near the Shin Koe Shin Pagoda road at the base of Kalain Aung Mountain.

The explosion injured a 13-year-old girl and a 60-year-old man named U Kyaw Myint, both residents of Inn Pyar village. They sustained injuries to their hands and legs.

“The shelling continued throughout the night. The injured were finally taken to the hospital the next morning. They are currently receiving treatment at Kalain Aung Hospital,” said a resident of Kalain Aung town.

The artillery fire persisted until 1 a.m., preventing the safe transport of the injured to the hospital until the morning of January 6. The relentless shelling has left local civilians in a state of fear and anxiety.

The attack followed an incident on January 4—Independence Day—when resistance forces targeted the junta’s Kalain Aung Bridge checkpoint. In response, junta troops shelled nearby areas, including Inn Pyar and Zin Bar villages, for two consecutive days.

Following the bridge attack, the junta temporarily closed the bridge for about three hours and interrogated and assaulted several youths from Ward 1 near the bridge, according to a resident. The incident also affected local schools, with Kalain Aung High School closing for the day on January 6 due to safety concerns expressed by parents.

In a related incident on December 29, two villagers from Zar Dee village in Yebyu Township were injured after stepping on landmines allegedly planted by junta forces.

Another attack took place just days later, during the first week of January. On the morning of January 8, the Ye-based Military Operations Command No. 19 of Mon State Junta launched continuous artillery and missile attacks on Kyone Laung (Old Village) and surrounding areas east of Ye Town. The relentless shelling continued into the afternoon, forcing residents and rubber plantation workers to flee for their safety.

The highway bridge connecting Ye to the Dawei road was closed from the early morning until midday, while nearly 100 junta troops were seen advancing toward Ye-Kyone Laung village. Despite the absence of active clashes, the junta continued its indiscriminate attacks using heavy artillery.

“Local villagers from the village and nearby farms are escaping. The junta started firing after receiving news about PDF military operation movements. The rubber plantation workers in the area are too scared to stay. Most people are fleeing towards Wae Paung village and some to New Mon State areas. There wasn’t even a battle—it was just shelling. The shelling is heavier this time than before,” said a Kyone Laung (Old Village) resident at 3 PM.

Although no homes in the village were directly hit, schools in Kyone Laung and neighbouring towns have been temporarily closed due to the attacks. Locals also reported that the military had positioned artillery units in the hills beyond the main Ye Bridge, indicating preparations for further assaults.

The shelling has disrupted transportation between Ye and the eastern villages, cutting off access and leaving residents in fear of more attacks. The situation remains tense as communities brace for further military actions.

More than 100 residents of Kyone Laung Old Village in Ye Township were forced to flee after the junta launched an offensive with relentless artillery shelling for two days. The attack began at 4 AM. on January 8, with junta forces stationed at Ye Bridge and nearby outposts firing artillery shells continuously until 9 a.m. while advancing on foot. The intensity of the shelling, combined with the troop movements, left villagers with no choice but to flee to safer areas.

“Most of the shells landed in rubber plantations. There were more than 20 rounds of indiscriminate artillery fire. People were terrified and fled to safer places, including areas controlled by the New Mon State Party,” a male resident of Kyone Laung shared.

The junta’s offensive reportedly followed intelligence suggesting that PDF (People’s Defense Forces) members were active near the village. This led to sustained artillery fire and an on-foot advance by the troops.

The impact on the community has been devastating. Schools in the village have been forced to close, and nearly 200 villagers have been displaced. In one instance, a shell exploded near a local school, prompting a two-day closure for safety reasons.

Kyone Loung (Old Village) has endured frequent shelling by the junta in the past, with artillery rounds hitting homes, rubber plantations, and even schools. These attacks have caused injuries and property damage and forced countless families to abandon their livelihoods and seek refuge elsewhere. The ongoing violence has left the community fearful and uncertain about when—or if—they will be able to return home.

At least five schools near the conflict areas in Ye Township, Mon State, have been forced to close due to the ongoing clashes. More than 400 students are currently unable to attend classes.

Fighting broke out on January 9 between junta forces and joint resistance groups near Kyone Laung old village. The intensified conflict has impacted nearby towns, including Kyone Laung and Kyauk Mi Chaung, where two primary schools have been forced to shut down. In Wae Zin, Dhamma Pala, and Wae Paung villages, three Mon National Primary Schools have closed since January 10.

“None of us wanted to close the schools. However, the artillery shells have continuously fallen near Wae Zin and Wae Paung villages in eastern Ye Township. Parents came to take their children home; eventually, no students were left. Even the teachers had to flee to safer places,” explained a teacher from one of the Mon National Schools.

The teacher also noted that many families fled their homes alongside the teachers, seeking safety in nearby villages and forested areas. The closures are critical, as final exams are typically held in February. Both parents and school officials are worried about the educational setbacks their children will face due to the disruption.

As of January 15, gunfire has quieted in Kyone Laung village and its surrounding areas. However, a resident reported that junta forces sporadically fire artillery shells, maintaining a heavy military presence. The ongoing conflict has not only displaced families but has also severely impacted the children’s education, leaving communities in a state of uncertainty and fear for what lies ahead.

On the evening of January 21, 2025, an artillery strike by junta forces tragically claimed the life of one civilian and left three others injured in Hnapyawdaw village, Kyaik Hto Township, Mon State. According to HURFOM field reporters, the attack caused severe damage to homes and personal property, sending shockwaves through the community.

Between 6:35 PM and 6:55 PM, two rounds of 120mm artillery shells fired from the junta’s Artillery Regiment Command No. 602, struck the village. One of the shells hit the home of U Tin Naing Oo and Daw Aye Cho in Lower Hnapyawdaw village, killing Daw Aye Cho, 54, instantly. Her daughter, 15-year-old Yun Nadi Oo, sustained critical injuries to her legs and body.

Two other villagers, 15-year-old Ma Lae Lae Khine and 60-year-old Daw Khin Nyunt, were also injured by the shelling, suffering severe wounds to their chests, arms, and other parts of their bodies. They were immediately transported to Kin Moom Chaung General Hospital in Kyaik Hto Township for treatment.

The attack also caused extensive damage to three homes, a vehicle, and household items. Despite the destruction and loss of life, reports confirm that there was no ongoing conflict or activity by resistance forces near the village at the time of the incident.

This tragedy is not an isolated event. On December 21, 2024, a similar artillery strike by junta forces injured three civilians in Ta Gay Chaung Pyar village, also in Kyaik Hto Township.

The repeated and indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas underscores the escalating violence faced by communities in Mon State, leaving residents in fear for their lives and struggling to rebuild amid the ongoing turmoil.

Forced Conscription

The junta’s forced conscription efforts are a direct response to the declining morale and mass defections within the Burmese military, exacerbated by intensified offensives from Ethnic Resistance Organizations (EROs) and People’s Defense Forces (PDFs).

In recent months, there have been notable cases of high-ranking military officials surrendering, which has pressured the junta to forcibly recruit civilians into the army. This enforcement of the People’s Military Service Law (2010) is unlawful and violates fundamental human rights.

HURFOM’s recent documentation in its target areas has further highlighted the forced recruitment of young men and youth, particularly in rural areas, with testimonies indicating that these individuals are often taken without consent and sent to the frontlines. Families report that these youths are being used as expendable forces, with many losing their lives in conflict zones.

On December 28, 2024, ten residents, including the local administrator, were arrested in Thuwanna Wadi Town, Thaton Township, Mon State, after speaking out against the junta’s forced conscription on social media, according to family members and local sources.

Among those detained was the administrator of Thein Seik Ward, U Paung Paung, who had posted a critical message on his Facebook page condemning the military’s practice of forcibly recruiting local youth:

“The administrator openly opposed forced conscription and even wrote that he wouldn’t comply if asked to assist. Many of his friends and business owners commented their support beneath his post. The next night, everyone who commented was arrested,” shared a family member of one of the detainees.

The list of those arrested includes U Paung Paung, the ward administrator, and several community members, such as U Tun Naing, the local Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) chairman, his son, and prominent figures like Daw Aye Thida, a headmistress. Residents U Aye Lwin, U Myint Lwin, U Phoe Htaung, and U Kyi Khine are also included. Most of them are small-scale business owners involved in the brick industry.

Reports indicate that U Tun Naing and his son were released on January 1, 2025, but the remaining eight individuals are still being held at the No. 9 Military Training Camp in Thaton. Forced conscription remains a grave concern in Thaton Township. Throughout December 2024, at least 30 youths were forcibly taken by junta troops to serve in the military, according to local sources.

A similar incident occurred in Mottama Village, Paung Township, on December 25. During a festival at Kywe Chan Village, a junta-aligned task force led by the local police chief abducted 30-year-old U Aung Myo Hlaing around 10 p.m., forcibly conscripting him.

“They waited until the village was celebrating and quietly took him away. When the local administrator was asked, he confirmed that the military had taken him. But no one dared to go to the station to ask for more information. His family is devastated—they are struggling and can’t do anything,” said a family member.

With battlefield losses mounting, the Junta appears increasingly desperate to replenish its ranks. Reports from regional and local news agencies and research groups indicate that in Mon State alone, more than 2,100 to 2,300 civilians have been subjected to forced military training under various “People’s Militia” programs.

The junta’s practice of targeting local communities for forced conscription has fueled fear and outrage, as many families are left without their primary breadwinners, and communities face growing instability.

Reports from HURFOM field sources reveal that the junta has intensified forced conscription efforts as part of their recruitment for the 9th round of military training. These operations primarily target young civilians across Mon State, with a focus on areas under firm junta control. Local administration officials, junta-backed militias, and village leaders are leading door-to-door operations to detain youths and transport them to military camps forcibly.

In the past, the families of detained youths could pay ransom to secure their release. However, since the beginning of this year, such arrangements have become increasingly rare, and only individuals with close ties to the junta are reportedly able to negotiate for their children’s release.

Starting on January 17, junta forces, including members of the General Administration Department (GAD) and security forces, targeted 35 villages across seven townships—Mudon, Kyaikmayaw, Mawlamyine, Paung, Mottama, Bilin, and Thanbyuzayat. These operations aim to meet the conscription quotas set by the Southeast Command. A leaked directive from the Southeast Command’s Commander-in-Chief warns local officials that they will face penalties if quotas are not met.

Local sources confirm that over 60 youths have already been detained since the beginning of January, with at least two dozen still missing. A parent from Mudon Township expressed frustration: “The forced arrests are increasing. They no longer prepare or summon youths via household registration lists. Instead, they show up armed and, along with village administrators, forcibly take youths from their homes.”

The worsening situation has left many parents scrambling to hide their children or claim their sons have left the country. Those unable to protect their children face steep fines ranging from 100,000 to 500,000 kyats if their family members are deemed “unavailable.”

In some areas, including parts of Mudon, Chaungzon, and Paung Townships, locals report collecting significant bribes to avoid conscription. A resident from Chaungzon Township shared:

“They force households to pay varying amounts as fees to replace conscripts or for military expenses. The amount depends entirely on the village administrator, who knows which families can afford to pay and which cannot.”

The junta has also escalated nighttime arrests. In Mawlamyine Township, residents report that youths found outside after dark are being detained and conscripted.

A local explained: “At night, the junta arrests young people they encounter outside, while during the day, they stop and detain those traveling in and out of town, using conscription as a pretext.”

In towns like Kyaikmayaw, Mawlamyine, Ye, and Thanbyuzayat, increased checkpoints and stop-and-search operations have been reported, focusing on targeting youths. A resident from Ye stated:

“In the last week alone, we’ve recorded at least 12 young people who disappeared after being taken at checkpoints. The situation is becoming more frightening every day.”

Parents and guardians are now urging young people to stay indoors whenever possible. A Mawlamyine resident shared:

“Families are telling their children not to go outside unless absolutely necessary. We’ve even seen traditional festivities and gatherings decrease because of the fear of arrest.”

The escalation in forced conscription has deepened distrust and fear among communities. A father of two sons from Thanbyuzayat shared his concerns:

“Previously, we could pay around 1 million kyats to secure the release of our sons, but now, only families with connections to the junta seem to have that option. For the rest of us, they take our children to training camps with no way to get them back.”

The arbitrary arrests and forced conscription by the junta are contributing to a growing humanitarian crisis, with countless families torn apart and many youths either detained or forced into hiding.

HURFOM’s data shows that forced conscription and arbitrary arrests are a growing pattern in junta-controlled areas, leading to widespread fear, displacement, and financial exploitation of families.

Residents in Mawlamyine, Mudon, Kyaikmayaw, and Thanbyuzayat Townships report that local administrators, acting under orders from the General Administration Department, are visiting homes to collect household lists. These lists are being used to identify individuals eligible for forced military service, leaving families anxious and vulnerable.

The process has become a significant source of extortion, with families being forced to pay large sums to avoid conscription. Parents of youths working abroad are mainly targeted, with demands for bribes ranging between 6 to 8 million MMK per person.

HURFOM field reporters have confirmed several cases in Mon State during these days:

Three cases in Mawlamyine Township,

Two cases in Mudon Township,

Two cases in Thanbyuzayat Township.

“Parents with their son/daughter overseas are forced to pay more because the authorities demand proof of their location and employment abroad,” said a 60-year-old parent from Mudon Township. “If we can’t provide documents, we risk legal action under the conscription law.”

Disturbing reports of young people disappearing while traveling have heightened fears. On January 26, junta forces stopped two express buses on the highway between Mudon and Thanbyuzayat, detaining at least 12 young passengers.

In a separate case, eight youths traveling from Yangon to Ye have been reported missing for over four days.

A resident from Kyaikmayaw urged families to take immediate action:

“Check nearby military camps or training centers if your children haven’t returned home. For young people, I would advise staying indoors unless necessary. If you don’t want to serve, staying in hiding is safer; otherwise, you risk being taken by the Junta.”

The junta’s township-level conscription committees hold unchecked power, using legal provisions to exploit families. Parents are required to provide detailed documentation, such as employment contracts and departure records, for youth working abroad. Without such proof, families risk their children being forcibly registered or declared fugitives.

A legal expert in Mawlamyine explained:

“According to their law, parents must submit valid proof of their children’s status, including details from labour agencies or employers abroad. If they fail to provide this, their children will be forcibly registered and could face arrest warrants or be declared fugitives.”

The enforcement of the conscription law has compounded the suffering of civilians, many of whom are already struggling under the Junta’s oppressive rule. The Junta has set a recruitment quota of 5,000 conscripts per batch, with the 9th batch underway. As a result, many youths have gone into hiding, separating families and deepening the humanitarian crisis.

One parent, devastated by their child’s disappearance, shared:

“We are powerless. They take our children, extort money from us, and punish us if we don’t comply. This law is designed to destroy families and communities.”

The People’s Military Service Law, issued on January 23, 2024, establishes strict regulations for conscription, targeting both civilians and skilled professionals. This law requires males aged 18 to 35 and females aged 18 to 27 to serve. For trained professionals, such as doctors and engineers, the age limits extend to 45 for males and 35 for females.

The law imposes severe penalties for non-compliance. Individuals who fail to register for conscription can face up to three years of imprisonment, a fine, or both. Those actively avoiding military service are subject to harsher penalties, including up to five years in prison—additionally, family members who assist in evading conscription risk one year of imprisonment.

This law also enforces travel restrictions, prohibiting conscripts and those eligible for service from leaving the country without explicit permission from the Junta’s central committee. Although the standard conscription term is two years, the junta reserves the right to extend it to five years during emergencies.

Landmines

HURFOM reported on several cases of landmines, specifically affecting internally displaced people. Two internally displaced men returning home from an IDP site in Tanintharyi Township encountered a tragic fate after stepping on a landmine. The incident occurred near Chaung Hnit Pauk village in Thein Khun village tract, Myeik District, resulting in one death and another man being severely injured.

On the evening of January 1st, U Zaw Min, a 40-year-old displaced resident, and another local man were temporarily returning to their village when the explosion occurred.

“A landmine exploded as they were walking back from the IDP site to the village. The second man sustained injuries to his hands and legs,” explained a resident familiar with the incident.

U Zaw Min died instantly at the scene, while his companion is now receiving medical treatment for his serious injuries. The recent surge in clashes and advancing junta troops have displaced civilians from over ten villages, including Chaung Hnit Pauk, since mid-December. Many residents have been forced to seek shelter in remote, makeshift camps to escape the violence.

Just days before the New Year, a similar tragedy unfolded in Yebyu Township when two villagers from Zar Dee village stepped on a landmine, destroying their motorbike and leaving both men injured.

The persistent dangers of landmines highlight the ongoing peril faced by displaced communities as they navigate through conflict zones, attempting to survive amid the chaos and uncertainty.

In another case, a male villager from Ma Yan Kone village, Chaung Hnit Kwa village tract in Kyaikmayaw Township, Mon State, lost his life after stepping on a landmine near the village entrance.

On January 9, at 4 PM., the couple was returning home from their paddy field. As they reached the uphill road near the village entrance, the man, U Chit Ma Kon, who was in his 40s, was pushing their three-wheeled motorcycle with one foot when he accidentally triggered a buried landmine. The explosion severely injured him.

Despite efforts to rush him to Mawlamyine Hospital, he passed away on the way due to significant blood loss. His wife, who was riding with him, sustained minor injuries to her hand from shrapnel, but her condition is stable.

“They had just finished fertilizing their paddy field and heading home. As he pushed the three-wheeler uphill, the landmine exploded. Everyone tried their best to get him to the hospital, but he lost too much blood,” a resident shared.

The area near the entrance of Ma Yan Kone village and surrounding locations remains dangerous due to the presence of unexploded landmines and military weapons left behind after clashes. At least four landmine-related incidents have occurred in the area.

In mid-November 2023, intense fighting broke out after joint resistance forces attacked the Chaung Hnit Kwa police station and the security post at Attaran Bridge. The clashes forced thousands of residents to flee their homes for safety.

The continued presence of junta troops and the threat posed by leftover landmines and unexploded ordnance have prevented many families from returning home, leaving them displaced and living in fear of further tragedy.

Mon State

In Mon State’s Bilin Township, ongoing airstrike threats by the junta have forced nearly 5,000 residents from 15 villages to flee their homes, according to officials from the Karen National Union (KNU) in Thaton District.

Since December 24, the junta’s forces have been conducting relentless aerial surveillance and attacks in the area. On December 30, Karen New Year’s Day, at least four bombs were dropped near Kya Taung Seik village and surrounding areas, causing widespread panic and destruction.

Following the airstrikes, the junta continued its aerial patrols, leaving residents in constant fear for their safety. Villagers from areas including Kya Taung Seik, Pyin Ma Pin, Myit Kyoe, and Min Saw Ah villages have sought refuge in caves and bomb shelters, totalling 4,875 displaced individuals.

“The junta’s aircraft come daily, so the villagers can’t stay in their homes anymore. Most are hiding in caves for safety. We are doing our best to provide food supplies to those in need,” said Padoh Saw Aye Naing, the secretary of KNU Thaton District.

The 15 affected villages are located in the KNU-controlled area of Bilin Township under Brigade 1 in Thaton District. These communities are predominantly home to Karen ethnic villagers.

On December 31, the KNU issued a statement strongly condemning the junta’s airstrikes, which disrupted the celebrations of the Karen New Year—a day of cultural and spiritual significance for the Karen people. The organization expressed deep outrage over the attacks and called for accountability.

The ongoing crisis in Mon State reached alarming levels in December 2024, as the junta intensified its campaign of violence against civilians. According to HURFOM’s latest reports, 13 civilians were arrested, and nine were tragically killed within a single month.

From December 1 to 31, military junta forces captured seven men and six women across the townships of Kyaik Hto, Bilin, Thaton, Ye, and Thanbyuzayat. Ye Township recorded the highest number of arrests, with four men and three women detained. While one woman from Mawkanin village in Ye Township was later released, the fate of the others remains uncertain.

The indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas and landmine explosions claimed the lives of 9 villagers and injured 10 others. In addition to the loss of life, the junta’s forces looted homes, stole property, and caused widespread destruction, particularly in the townships of Ye, Thanbyuzayat, Bilin, and Kyaik Hto, as well as parts of Mawlamyine City.

The military’s operations have included artillery assaults during at least nine separate clashes in Thanbyuzayat, Kyaik Hto, and Bilin townships, forcing over 10 villages in Thanbyuzayat to evacuate in fear for their lives.

The uptick in clashes, particularly in Mon State, has led to rising cases of forced displacement. Ongoing clashes between junta troops and joint resistance forces near Kyone Lone Old Village in Ye Township, Mon State, have forced nearly 1,000 residents to flee to safer areas as of January 12.

Junta artillery units based in Ye, including Artillery Battalion 316, Inspection Command Headquarters 19, SAC Battalion 19, Infantry Battalion 61, and Light Infantry Battalion 591, have been launching relentless shelling and conducting airstrikes. These assaults have forced residents from Kyone Lone Old Village, Kyauk Mi Chaung, Kwin Shay, Wae Paung, Wae Zin, and nearby areas to evacuate completely.

Over 420 displaced residents, including women and children, have sought refuge in Dhamma Pala Village, a New Mon State Party (NMSP)- controlled area. Others have sought shelter in the surrounding locations, including villages in the Kyone Lone village tract, Lake Poke village, and parts of Ye Town.

“Entire villages have been emptied because of the heavy artillery shelling. Two locals were also shot dead by the junta forces,” a resident shared.

The two villagers who lost their lives were found near Ai Poke Village. However, no one dares to retrieve their bodies due to the ongoing presence of junta troops.

On January 10, two residents injured by artillery fire were being taken to the hospital when junta soldiers stopped their vehicle near Ai Poke Village. After spotting food containers in the car, the soldiers accused the injured individuals of delivering supplies to resistance forces and executed them on the spot.

“The bodies of the two locals are still near Ai Poke Village. No one dares to collect them because SAC forces remain in the area,” said a source from Ai Poke.

Currently, a large junta force is stationed near Dhammi Karyone Monastery, Bo Kalay Taw Ra Monastery, and Ai Poke Village along the Ye-Ye Chaung Pyar road.

The junta began shelling on January 8 after receiving reports that joint resistance forces were advancing toward Kyone Lone Old Village in Ye Chaung Pyar. The clashes have since escalated, with fighting involving Mon resistance forces, the NUG-PDF’s Daw Na Column, ABSDF joint forces, and junta troops continuing from January 9 to January 12. These ongoing clashes have left communities devastated, forcing families to abandon their homes and live in constant fear as the conflict rages on.

Following fighting near Kyone Laung Old Village in Ye Township, Mon State, junta forces have tightened their control over the township’s main entry and exit routes, imposing strict inspections on both local civilians and travellers. These restrictions have also extended to a ban on transporting essential goods, especially staple items such as rice and cooking supplies, even between neighbouring villages.

This blockade has led to growing concerns over severe food shortages and the inability to access daily necessities and medical supplies for displaced villagers (IDPs).

Since January 12, reports indicate that junta forces have only allowed limited quantities of rice and dried goods to be transported into Kyaung Ywa village. Any amount exceeding one bag of rice has reportedly been confiscated.

“The restrictions have tightened. No rice can be transported from Ye anymore. Just yesterday, SAC forces seized food supplies from a group of locals who had brought goods from a nearby New Mon State Party village. There’s no proper checkpoint—soldiers stop people randomly. Now, even in Kyaung Ywa, rice, oil, and medicine are in short supply. No one dares to travel the road between Kyaung Ywa and Ye Town,” a resident explained.

Local shops in Kyaung Ywa village have run out of essential goods, forcing many to close due to a lack of stock. Due to the ongoing conflict, residents remain cautious about movement, and children are kept at home for safety.

Clashes between junta forces and joint Mon resistance troops near Kyone Laung Old Village began on January 9 and have continued without pause. The junta has reportedly used heavy artillery from bases in Ye Town and conducted airstrikes in the area. The violence has forced entire villages, including Kyone Laung, Kyauk Mi Chaung, and Wae Paung, to evacuate. Most displaced residents have fled toward New Mon State Party-controlled areas.

The New Mon State Party’s Humanitarian and Development Department has been providing emergency food aid to the displaced villagers who arrived in their territory. However, humanitarian needs continue to rise as more people seek refuge from the escalating violence.

In Mon State’s Thaton District, indiscriminate artillery shelling by junta forces has killed two women and injured five others in recent weeks, according to local sources. The attacks have also caused extensive damage to homes, livestock, and property, leaving communities devastated.

On January 12, an artillery shell fired by Light Infantry Battalion No. 405 struck Asue Chaung village in Bilin Township, injuring one resident and destroying six houses. Two days earlier, on January 10, Light Infantry Battalion No. 44, an artillery fire hit Hnapyawtaw village in Kyaikto Township. The shells struck the home of U Aung Soe in Htee Nyar O Ward, causing injuries to Naw Aye, who suffered a severe wound to her left shoulder, while the house burned down, destroying 6.5 million kyats in cash and a collection of gold.

The violence extended to multiple villages in the area. In Hnapyawtaw, a house and 6 million kyats in cash were lost to a fire caused by shelling, while Nat Kyi village and Asue Chaung village reported a total of eight homes destroyed.

Locals report that even in the absence of active clashes, the junta frequently fires artillery indiscriminately into villages. In some cases, drones have been used to drop bombs on civilian areas.

On January 5, junta forces stationed in Mae Zali fired nine artillery shells toward Asue Chaung village, some of which landed on Saw Kaw Lar’s property, killing one cow, three buffalo, and two goats. Similarly, on January 3, Nat Kyi village (New Ward) was struck by an artillery shell fired by the junta’s Nat Kyi-based troops. The shell hit the home of U Than Htun, killing the 55-year-old resident and his 28-year-old niece, Ma The Ei Soe. Three other residents, Ma Khine Pu (35), Naw Hla Gae (19), and Daw Ah Maw (50), suffered injuries to their heads and arms.

Since 2023, ongoing military tensions have caused significant disruption in Dhammasa, Ta Ra Nar, Kaw Swell, Kaw Thut, Kha Yone Gu, Than Ga Long, and Kyune Gone villages in Kyikemayaw Township, Mon State. Villagers have been unable to return to their paddy fields due to unexploded bombs and landmines left behind after armed conflicts, resulting in a growing rice shortage in the region.

“After the fighting, bombs and landmines were scattered across our fields. The military has warned farmers not to return to their farms, so no one dares to return. We’re relying on last year’s rice stock, but now that’s running out. We can’t even buy rice in the village,” shared a resident.

With the dwindling rice supply in villages, residents are forced to travel to nearby cities to purchase rice. However, prices in urban areas have skyrocketed, with a single bag of rice costing up to 200,000 MMK.

“Rice from the villages is usually cheaper, but people hold onto what they have because of the uncertainty. They don’t want to sell their stock. Those of us who don’t farm are left with no choice but to go to the cities and buy rice at very high prices,” another villager explained.

The junta’s restrictions further exacerbate the situation. According to local sources, the military regiment stationed in Kaw That village, Kyikemayaw Township, has banned the transportation of rice and confiscated food supplies from anyone attempting to transport it.

The continued instability, combined with the lack of access to farmland and food restrictions, has left many families struggling to secure their basic needs. As the rice shortage deepens, residents remain trapped between insecurity and rising costs, with no immediate solution.

Further, the junta’s ongoing artillery shelling and drone strikes in Kyaik Hto and Bilin townships, Mon State, have left residents living in constant fear. Since the second week of January 2025, the intensified attacks have caused injuries, destroyed homes, and forced villagers to either flee or seek shelter in makeshift bomb shelters.

In Kara Wai Sate village, Bilin Township, junta troops from Battalion 44 launched artillery shells on January 18 at around 1 p.m., targeting areas near the road connecting Nget Pyaw Taw and Ta Gay Chaung Pyar villages. One shell exploded in front of U Shwe’s shop and home, leaving him with minor injuries to his forehead, ear, and face. The blast also caused significant damage to his house and shop.

Drone strikes and artillery shelling have wreaked havoc across the region, destroying homes, monasteries, and even public water ponds. Many villagers have been forced to flee, while others remain in their homes, seeking refuge in bomb shelters during the attacks.

“They are firing artillery randomly and using drones to drop bombs. Villagers’ homes are being hit continuously,” said a resident.

On January 19, around 11 AM., Artillery Battalion 310 launched a shell from its Thane Zayat base toward Kha Ywel village in Kyaik Hto Township. The strikes destroyed electrical lines, causing a power outage, and burned down Ko Moe Min’s home.

Earlier, on January 17, Light Infantry Battalions 404 and 405 from the Mae Pa Lee outpost fired a 120 mm artillery shell into Asuu Chaung village, Bilin Township. The shell destroyed a shrine, a pond, a monastery, and a house. The following day, another shell landed near the village, although no injuries were reported. These attacks have forced thousands of locals to evacuate nearby towns, including Asuu Chaung, Mae Pa Lee, Wa Dut Kwin, and Kha Ywel.

Despite the constant threat of shelling, some villagers in Kara Wai Sate have chosen to stay but hide in bomb shelters during attacks, resuming their activities once the shelling subsides.

Tragically, on January 3, an artillery shell fired from the junta’s Nat Gyi base in Bilin Township hit U Than Htun’s house in the new ward of Nat Gyi village. The blast killed U Than Htun, 55, and his 28-year-old niece, Ma Thae Ei Soe, instantly. Three others—Ma Khine Pu, 35, Naw Hla Gay, 19, and Daw Ah Maw, 50—sustained head and arm injuries.

The situation in Kyaik Hto and Bilin remains dire. In December 2024 alone, four civilians were killed and five others injured in Kyaik Hto and Hpa-An townships due to similar artillery attacks within KNU Brigade 1’s territory.

Karen State

Residents along the Thanbyuzayat-Three Pagodas Road, connecting Mon and Karen States, are being forced to relocate to Thanbyuzayat town due to escalating battles, advancing military troops, and the constant threat of landmines and unexploded ordnance. Local sources confirm that the ongoing violence has upended lives and livelihoods.

Although Sakhan Gyi village has not witnessed daily clashes, the frequent explosion of landmines and the presence of advancing troops have halted rubber plantation operations. This disruption has caused severe hardship for plantation owners and workers dependent on this livelihood.

“People in Ye Ta Kon and surrounding areas are terrified after hearing about landmine explosions. Plantation owners and workers no longer dare to go into the fields” shared a resident.

The human toll of this crisis is devastating. Between August and December 2024, eight men and four women working in plantations lost limbs due to landmine explosions, and one resident of Pa-Nga village tragically lost their life.

Since mid-2024, the continuous clashes have driven most residents from nearby villages to seek refuge in Thanbyuzayat town. Many have rented apartments, purchased homes, or found temporary shelter, causing real estate prices to soar. Rubber plantation owners, unable to continue operations, are selling off their land and businesses to escape the risks.

“We hear artillery fire almost every day. Even when there’s no fighting, they still fire their weapons. People have abandoned their rubber plantations and moved to town. It’s getting harder and harder to make a living,” lamented a plantation worker struggling to survive.

The New Year holidays brought further fear as intense fighting erupted near the Anan Kwin strategic base between junta forces and resistance groups. The crisis has also left young lives shattered. A heartbreaking example is the story of 16-year-old Ma Mon Hnin Soe, who was injured in a landmine explosion and lost an eye, a painful reminder of the indiscriminate harm caused by the conflict.

As the violence persists, families continue to live in uncertainty, hoping for safety and a chance to rebuild their lives.

On January 22nd, an airstrike by the junta claimed the life of a woman in Kyaik Don, Kawkareik Township, Karen State, according to a statement released by the Karen National Union (KNU). At 7 AM,, a Yak-130 fighter jet from the Naypyidaw Air Force dropped bombs over Kyaik Don town. The attack resulted in the death of 51-year-old Daw Nyo Nyo Win, who was returning home after tapping rubber. Several unoccupied civilian homes were also damaged in the bombing.

In addition to this tragic incident, on January 21, an airstrike in Kyon Sein village, Hpa-an Township, destroyed approximately 300 rubber trees after bomb fragments scattered across the plantation.

Similarly, on January 11, without any ongoing clashes in the area, a junta airstrike targeted Yohkadaw village in Kyainnseikyi Township, which is under KNU control. The bombing severely damaged a local school building. The junta has been deliberately targeting civilian villages through airstrikes and ground-based artillery attacks. According to the KNU, these deliberate assaults constitute daily violations of human rights and war crimes.

Tanintharyi Region

Since December 17, 2024, the Junta has intensified its offensive in the Tanintharyi Region, triggering fierce clashes with local resistance forces in villages along the Dawei-Myeik road, including Yebyu, Thon Khar, Chaung Hnit Pauk, and Thane Khun.

According to an official from the Tanintharyi Student Unions’ Network (TSUN), the ongoing conflict has sharply increased the number of displaced residents.

“The number of displaced people has risen from 2,000 to around 6,000. Given the situation, they urgently need food and medical supplies, as well as long-term essentials like shelter, clothing, and warm blankets,” the official explained.

Many displaced villagers have sought refuge in forests and farmlands to avoid urban areas due to safety concerns. However, life in these makeshift shelters has become increasingly complex, with limited access to food, water, and shelter.

A member of the Ngwe Oo Mitta Humanitarian Aid Group, which has been assisting the displaced, described the challenges:

“As social workers, we have to cross conflict zones to deliver supplies, which makes it incredibly difficult to reach those in need. Even when we manage to transport food and medicine, the intensity of the fighting makes distribution nearly impossible.”

Due to harsh winter conditions, the health of the displaced residents has also deteriorated. Due to the lack of clean water and proper sanitation, cases of severe colds, coughs, and diarrhea—sometimes with blood—have increased.

“Food and medicine are the most urgently needed. Many are suffering from flu due to the cold, and unclean food and water have caused severe diarrhea. Warm clothing, blankets, and temporary shelters are critical to protect them from the cold,” said another humanitarian worker from Ngwe Oo Mitta.

The ongoing conflict along the Dawei-Myeik road has turned the area into an extended battlefield, leading to travel restrictions, arbitrary arrests, and reports of missing family members.

As the junta advanced toward Thane Khun, the fighting escalated. There have also been credible reports of villagers being abducted and used as human shields, homes being raided and looted, and women being subjected to sexual violence.

In addition, local sources say displaced residents seeking refuge in Phaung Taw village tract, Yebyu Township, are being forced to apply for identification letters. The junta-appointed village administrator has required internally displaced people (IDPs) from Zar Dee village tract in Kanbauk Sub-township, Dawei District, to complete detailed registration forms since the last week of December.

The identification letters include personal details such as full name, previous residential addresses, current relocation addresses, and attached photographs. Once processed, copies of these letters must be submitted to the Mawrawaddy Naval Headquarters, the Byu Saw Htee checkpoint in Mawgyi village, and the local administrator.

Residents have reported that fees for these identification letters range from 5,000 to 20,000 kyats.

“IDPs from Zar Dee village tract are being forced to register. The format is similar to a guest registration form. There’s no fixed fee, but people are being asked to pay anywhere between 5,000 and 20,000 kyats,” said one displaced person who recently applied for the letter.

This is not the first time such measures have been imposed. In October last year, displaced residents and rubber plantation workers in the Phaung Taw village tract were also forced to apply for identification letters for 20,000 kyats per person.

Displaced people living in temporary shelters across Phaung Taw, Thae Chaung, Ohn Pin Kwin, and Kanbauk village tracts are also required to register as “guests.” Since last year, the junta-appointed administrator has warned that local villagers will be held accountable if they fail to register their guests.

The latest wave of displacements was triggered by two battles in Zar Dee village tract in June and December 2024. These clashes forced residents from five villages to flee to nearby areas for safety.

The increasing bureaucratic demands and forced fees place an additional burden on displaced communities, many of whom are already struggling to survive after losing their homes and livelihoods due to the conflict.

Airstrikes also continue to threaten the safety and security of civilians. Residents of Ban Chaung in Dawei Township report that junta forces carried out an airstrike on Kwan Chaung Gyi village using fighter jets despite the absence of any active clashes in the area.

The attack occurred on January 7 at 11:45 AM. The village, located south of Myittar Town, was struck by two bombs dropped from military jets.

“Fighter jets carried out the strike. Two villagers near the village’s football field were injured. This isn’t a conflict zone or even a place with displaced people,” a resident shared.

The bombing caused significant damage to several homes in the village. According to reports, a man and a woman sustained injuries. The woman suffered wounds to her left arm, while the man was injured in his leg, chest, and left hand.

Additionally, residents reported that over 100 junta troops from the Kyauk Me Taung Police Station had arrived at the junta’s strategic base in Myittar about six days earlier, bringing weapons and supplies.

The attack has left the community shaken, with villagers now living in fear of further violence despite no apparent military threat in the area.

Another airstrike took place on the morning of January 13. Junta fighter jets launched an airstrike on Taku village in Tanintharyi Township, Myeik District, leaving five civilians injured and destroying four homes. At 8:30 AM, despite no active clashes in the area, two bombs were dropped over Taku village tract, with the first strike hitting near the Taku police station.

During the first airstrike, a 35-year-old local woman sustained severe injuries. The blast also destroyed two houses.

“She suffered serious wounds to her head, back, and legs,” shared a male resident of Taku village.

At approximately 9:45 AM., the second airstrike targeted the center of Than Taik village, close to the local school and the fresh market. Two bombs were dropped during this attack, with only one detonating. The second airstrike injured three women and one man and caused damage to two additional homes.

“There were shrapnel wounds on their hands, arms, and heads,” another resident reported.

The unexploded bomb from the second airstrike remains in the village, posing an ongoing threat to the safety of residents.

Just days earlier, on January 9, junta forces carried out over 23 airstrikes on Zayat Seik village in Palaw Township, dropping more than 70 bombs, according to a report released by the local People’s Defense Forces (PDF) Battalion 1 in Myeik District. The repeated airstrikes in the region have left many villagers displaced and living in fear, as homes, schools, and public spaces continue to be targeted.

On January 11, junta troops raided Zayat Seik village in Palaw Township, Tanintharyi Region, setting fire to five homes and over 50 acres of rubber plantations, according to HURFOM’s field report.

A military column of around 120 soldiers moved from Pada-Setaw-Yar Pagoda toward Thaposae-Eain-Su village. Around 1 p.m., a joint resistance force launched a drone attack, dropping bombs on the advancing troops.

In retaliation, the junta soldiers began torching homes and rubber plantations along their retreat route.

“Their troops were hit, so they started burning down everything as they withdrew—houses and rubber plantations between Thaposae-Eain-Su and Setaw-Yar village,” said a member of the local resistance.

The junta troops also arrested two men from Thaposae-Eain-Su village as they retreated. This isn’t the first time Zayat Seik has faced such destruction. In November 2024, after junta troops suffered casualties during a battle in Kyaung Neit village, they burned down 10 houses in the town as an act of reprisal. The ongoing military offensives continue to devastate local communities, leaving families displaced, homes destroyed, and livelihoods ruined.

On January 18, 2025, a junta artillery strike injured a woman. It destroyed two rubber plantations in Sein Bon village, Natkyisin village tract, Yebyu Township, Dawei District, Tanintharyi Region. The Kanbauk-based Mawrawaddy Naval Command reportedly fired two artillery shells into the area, allegedly after receiving information about the presence of local People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) in Sein Bon village. The shells landed outside the town in nearby rubber plantations, causing extensive damage.

One of the shells struck a rubber plantation, injuring 35-year-old Ma Aye Sein, who was processing rubber latex on her property at the time of the explosions:

“PDF members often come to the village to buy food from local shops. The junta likely targeted the area based on this information,” a resident explained. “Thankfully, the shells didn’t hit the village directly, but Ma Aye Sein was wounded while working on her plantation.”

The artillery attack also caused a fire that destroyed two rubber plantations, each spanning about 10 acres. Residents are deeply concerned about the indiscriminate use of artillery in the area, which has created a climate of fear and uncertainty. Ma Aye Sein received medical treatment for her injuries at the Yapu village clinic.

This incident is not isolated. On January 15, 2025, Mawrawaddy Naval Command also fired artillery shells at Natkyi village and surrounding areas, without any active clashes taking place. The attack injured an elderly disabled woman, according to local reports.

HURFOM’s data reveals that from January to December 2024, indiscriminate artillery shelling in Mon, Karen, and Tanintharyi regions resulted in 74 deaths and 168 injuries. The ongoing attacks highlight the devastating toll of the junta’s military operations on civilian lives and livelihoods.

Such indiscriminate shelling not only injures and displaces civilians but also destroys critical agricultural assets like rubber plantations, further worsening the humanitarian crisis in the region. Locals live in constant fear, unsure when the next attack might strike.

Residents of Sel-Mai Village Tract in Kawthoung Township, Southern Tanintharyi Region, are being forced to pay 50,000 kyat per household with at least one male family member. This demand is being imposed under the pretext of the Junta’s conscription law, according to local sources interviewed by HURFOM.

In the second week of January 2025, the junta military authorities issued orders to neighbourhoods and villages across Kawthoung Township, instructing village leaders to provide between three and five men per area for military service.

Following these orders, on January 13, 2025, the Sel-Mai Village Administrator, U Myo Aung, called a meeting to announce the collection of fees. He informed residents that each household with a male member must pay 50,000 kyat instead of providing a recruit. This policy applies to households whose male members have fled abroad or work far from the village. A resident explained:

“They said our village needs to provide five recruits. Instead of sending people, they’ve decided to collect money from every household with a male member. A family with five men must pay 50,000 kyat for each of them. Even if someone has left the country, the family still has to pay.”

The Ten-Mile Village Tract consists of eight neighbourhoods, and local sources revealed that the village administrator, U Win Kyaw, a Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) member, is collecting money. They claim this is not an official junta policy but rather a scheme orchestrated by these local authorities.

Reports indicate that the collection began on January 16. Residents also shared that the military threatened local authorities, warning that failure to deliver the required recruits would result in severe repercussions. As a result, night patrols and vehicle inspections have increased, leaving young men fearful of being forcibly conscripted.

Many young residents have fled to other areas or hid from sight to avoid the recruitment drives. “Some young people have run to the border or hid at farms and plantations. Others are staying indoors, especially at night,” said a villager.

Kawthoung Township comprises over 20 villages and five central wards, all facing heightened security risks and growing pressure from the Junta’s conscription demands. This escalating situation highlights the challenges faced by local communities under the junta’s military policies, which continue to impose fear and financial burdens on already vulnerable populations.

At the end of the month, Seven villagers, including two children, were injured in artillery shelling by the military junta on January 22 in Tanintharyi Township, Dawei District. The attack targeted Pa Wa village and East Thara Phon village, leaving several residents wounded and homes destroyed.

The junta’s 306th Artillery Battalion, based in Maw Tone village, fired four 120mm shells at Pa Wa village and three shells at East Thara Phon village around midnight. The shelling caused injuries to three women, three men, and two children in Pa Wa village, as well as one woman in East Thara Phon village. Among the injured, a man from Pa Wa and a woman from East Thara Phon sustained serious injuries. In addition, the attack destroyed two houses in Pa Wa village, one of which was completely burned, and damaged two homes in East Thara Phon village.

Ongoing military operations by the junta in Tanintharyi Township have significantly heightened tensions in the area, leading to frequent clashes with resistance forces. Villagers continue to live in fear amid the escalating violence, as artillery attacks and military offensives disrupt their lives and livelihoods.