“To Whom Do We Report?”: Land Seizure by MOGE for the Expansion and Straightening of the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay Gas Pipeline

April 18, 2011

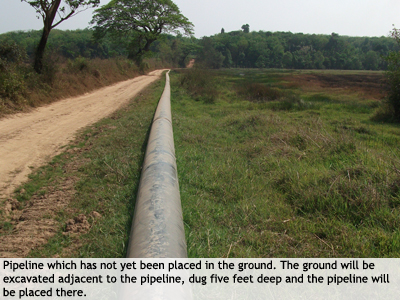

For the past four months, the government owned company, Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, has administrated extensive repairs and expansions to the gas pipeline from Kanbauk, Yebyu Township, in Tennaserrim Division to Myaing Kalay, Karen State. Repairs include the substitution of old parts of the pipeline, the straightening of the curved pipeline, as well as digging new roads for bulldozers and cranes to carry equipment to the pipeline areas. When expanding the pipeline, and paving new roads for the bulldozers, MOGE has cut through cultivator’s land and plantations, splitting up their plots and destroying their crops and livelihoods. Local landowners have expressed frustration and upset that not only has their land been destroyed, or broken into multiple parts, but that this acquisition of their land is the second time locals have lost their landholdings, whether it be rubber plantations, paddy land, or other farmland.[1] Download report as PDF [352KB]

Background

The construction of the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline began in 2000. It is a 180-mile long pipeline meant to supply cement factories and electricity generation projects along Burma’s southern peninsula. Documented in HURFOM’s May 2009 report, Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline, construction of the pipeline resulted in the seizure of more than 2,400 acres of land from cultivators, with insufficient or no compensation. This current report also reveals that nine out of the 13 (70%) interviewees for this month – farmers and land or plantation owners – had already lost land during the construction of the pipeline from 2000 to 2001, in addition to losing land for a second time during the current expansion.

According to MOGE, after ten years, the pipeline is in need of refurbishing. Though the Burmese government claims that the remodel of the pipeline and substitution of 20-inch diameter pipes for 30-inch diameter pipes is necessary due to the pipeline’s destruction by various insurgent, ethnic-armed groups, engineers working with MOGE have elaborated that the first construction included low quality pipes and materials and the pipes are in subsequent decay. HURFOM’s report, Laid Waste, also detailed the fact that most pipeline ruptures occurred from leaks in the pipeline and the low-grade pipes[2].

According to MOGE, after ten years, the pipeline is in need of refurbishing. Though the Burmese government claims that the remodel of the pipeline and substitution of 20-inch diameter pipes for 30-inch diameter pipes is necessary due to the pipeline’s destruction by various insurgent, ethnic-armed groups, engineers working with MOGE have elaborated that the first construction included low quality pipes and materials and the pipes are in subsequent decay. HURFOM’s report, Laid Waste, also detailed the fact that most pipeline ruptures occurred from leaks in the pipeline and the low-grade pipes[2].

The initiation of the pipeline, in conjunction with the increasing presence of army battalions to guard it, has resulted in numerous human rights abuses for villagers living nearby.[3] Though the repair of the pipes could have the potential of being beneficial to residents[4], the seizure of residents’ lands has limited, and even destroyed, many living near the pipeline’s livelihoods. The army consistently does not take the shape or outline of the resident’s acreage or land into account before bulldozing or excavating right through the middle of their land, either ruining or dissecting it.

Whereas in the past, villagers, land owners, and cultivators did not not receive compensation, certain villagers whose land has been destroyed, declared that this time they would not watch these abuses in silence, but instead, would document the land seizure in detail, and petition the government for compensation.

Interviews

The following interviews were recorded between February 20th and March 15th. Documents were collected from the households of local cultivators in northern Ye, Thanphyuzayart and Mudon Townships. Though HURFOM tried to cover all three regions aforementioned, local security conditions, strict checking of the government toll gates and check points, and the monitoring of the local pro-government groups and their secret informants, the information from most of the impacted local cultivators could not be collected. However, those interviews that HURFOM was able to conduct were in person and victims were able to explain and summarize the events in detail. The personal information and the names of the regions have been changed for the due security of the interviewees.

As a low-level engineer, working for MOGE, one 28-year old man explained that the Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline is being reinforced because it is 10 years old and decaying from inadequate technology and frequent explosions. This engineer explained that the number of pipeline sections will increase and the pipeline route is being modified and upgraded. On March 3rd, MOGE began the extension of the pipeline in Mudon and Thanbyuzayat Townships using welding machines, bulldozers, and cranes to carry the pipelines.

As a low-level engineer, working for MOGE, one 28-year old man explained that the Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline is being reinforced because it is 10 years old and decaying from inadequate technology and frequent explosions. This engineer explained that the number of pipeline sections will increase and the pipeline route is being modified and upgraded. On March 3rd, MOGE began the extension of the pipeline in Mudon and Thanbyuzayat Townships using welding machines, bulldozers, and cranes to carry the pipelines.

Wae-thon-chaung village, Thanbyuzayat Township, Mon State:

In the past, most pipelines were extended along with the railways and roads. The railways and roads are excessively curved because they were constructed during the Japanese era [World War II]. For example, the route near the Thanphyuzayart exit and the Mudon entrance route are excessively curved. Now, the MOGE of Naypyidaw are straightening the curved parts of the main route of the pipeline. Welding technology of the pipeline sections was modernized, so that there is almost no chance for accidental ruptures. Moreover, the pipelines were ordered to be made with thicker walls and Korea-made steel. [The steel] can prevent the underground ionization process. These pipelines can be used longer and an accidental rupture becomes less likely. It is more secure because 97 percent of the pipeline is underground.

By explaining that MOGE is installing superior quality pipes, this engineer essentially admits that the previous pipeline was made badly. MOGE never publicly admitting that leaks in the pipes may have resulted from its own construction of the pipes, has led to blame and subsequent taxation of villagers living near these pipes for ruptures and leakages. This taxation has been a very common form of punishment in which villagers were targeted solely for living near the pipeline in that area. Interviews with Sakhangi villagers in Thanpyuzayart Township revealed that 75% of the human rights violations committed against the villagers came in the form of levying taxes [fines] by the local authorities for pipeline leaks.

Min Tint Tun, a resident of a Mon village in northern Ye Township, during an interview in early March, explains how the pipeline, which is situated underneath a pond in his village, has a leak, and gas seeps into the water.

There is a pond near our village. The pipeline passes underneath that pond. That valley is where Daw Myint Than [aka Daw Mya Than]’s rubber plantation is situated. Now, the State confiscated the plantation saying it is pipeline land. When you look at the pond in the valley, you will see bubbles coming out due to a pipeline leak. There is a terrible gas smell that always comes out [of the pond]. Because of that, no one dares approach it. The particular authorities always come to supervise [check the leak]. Now [the land] has been re-excavated there. Daw Mya Than’s rubber plantation has been seized again [first in 2001]. The old area of the pipeline was not used and a new route was made. What is left of Daw Mya Than’s plantation is a long and thin shape. The rubber trees are still productive so it is really miserable [the rubber tree production was a current form of income for her]. Some trees are left.

There is a pond near our village. The pipeline passes underneath that pond. That valley is where Daw Myint Than [aka Daw Mya Than]’s rubber plantation is situated. Now, the State confiscated the plantation saying it is pipeline land. When you look at the pond in the valley, you will see bubbles coming out due to a pipeline leak. There is a terrible gas smell that always comes out [of the pond]. Because of that, no one dares approach it. The particular authorities always come to supervise [check the leak]. Now [the land] has been re-excavated there. Daw Mya Than’s rubber plantation has been seized again [first in 2001]. The old area of the pipeline was not used and a new route was made. What is left of Daw Mya Than’s plantation is a long and thin shape. The rubber trees are still productive so it is really miserable [the rubber tree production was a current form of income for her]. Some trees are left.

Due to the weakness of existing pipes during the extension of the gas pipeline, gas leaks or pipeline ruptures occur on average one time per month. According to Min Tint Tun, ruptures result from the use of low quality parts used by MOGE and that it is the villagers who suffer the most from pipeline ruptures:

We accept that they repair the pipeline and prevent the pipeline from leaking because we are [the ones] who directly suffered from ruptures in the pipeline. The minimum [repercussion villagers have to face] is having to pay for the leaked gas or being involved in countless [instances of] long-term forced labor. The worst is to be arrested and tortured. More than two times the pipeline ruptured near our village. The authorities forced the villagers to take responsibility for the consequences [of the rupture]. Now, we have accepted that we must repair [the pipeline], but we haven’t accepted that the villagers’ land has been unfairly seized. As everyone knows, we are really reliant on this land for our living so we are impacted even if one inch of land is lost. A huge number of rubber trees around our village were destroyed due to the new route of the pipeline. Betel-nut trees were also destroyed. Also, there has been no compensation for the land we lost in 2002. Now, again, I do not hear anything related to compensation. It seems that [this project] is a State operated project so no permission is needed from anyone.

Unfortunately, for the villagers living in pipeline areas, this new construction of the pipeline is not just simply the replacing of faulty and rusted pipes with better quality pipes, but also includes the expansion of the pipeline into areas previously untouched by it. These areas may be only a few feet over from the currently standing pipeline, but after the land seizure that took place from 2000 to 2001, villagers had to relocate their fields. These relocated fields of paddy or rubber plantation may have been just a few feet over from the former pipeline. What is seen in many of these interviews, though, is that many of those villagers whose land was seized over a decade ago, are experiencing land seizure of their property for a second time due to the pipeline.

Interviews collected between March 5th – 8th revealed that more roads were made for the bulldozers, which ruined the paddy land and plantation. The land was bulldozed for rerouting the pipeline and cranes were used to carry sections of the pipeline on the newly bulldozed roads. Nai Ah-Nyan, 45, a resident of Kwan-Hlar village of Mudon Township who makes his living from paddy fields explained:

Ours [the land] was ruined because of both the expansion [of the pipeline] and the construction of new roads for their bulldozers. My paddy mound[5] was destroyed because of the excavation for a new road for their bulldozers. According to their land needs for the pipeline extension, six squares [sections] of my paddy land was taken. Among these six squares of paddy, three squares were separated into two parts. Three squares were completely damaged and the others are salvageable. [The construction team] did not ask for permission. We are the people who are suffering the most trouble from this pipeline. Ten years ago, we lost our land because of this pipeline. My parents passed away in disappointment because [the seized land] was the land they inherited from their parents. They were truly unhappy. Now, we also can’t escape from the troubles caused by the pipeline. This land is our rice-pot [sustenance]. I have no [other] plantation and have to rely on this paddy land. [My land] has been ruined now and it means my rice-pot has been broken. I don’t want to go to Thailand for work but because of todays’ situation, I must go.

Nai Ah-Nyan continued that his elder brother was included in a group of people who were arrested on suspicions resulting from a 2003 gas pipeline rupture in Kwan-Hlar village, and his family had to pay around 80,000 kyat to guarantee his brother’s escape.

Nai Ah-Nyan continued that his elder brother was included in a group of people who were arrested on suspicions resulting from a 2003 gas pipeline rupture in Kwan-Hlar village, and his family had to pay around 80,000 kyat to guarantee his brother’s escape.

With no belief that he will be compensated for his land, the only other option for Nai Ah-Nyan appears to be leaving his home town and migrating illegally to Thailand for work opportunities. The pipeline construction has been quite successful in pushing ethnic people off of their land and forcing them to relocate either within their home state or traveling illegally to Thailand for work option. Currently, there are over two million migrant workers from Burma working in Thailand.

In the 1960s, the Burmese government began a campaign called the “Four Cuts.” This campaign was designed to put pressure on ethnic minority groups and living in the border areas to weaken the connection between insurgent groups and ethnic villagers. The four cuts pertains to food, funds, intelligence, and recruits. The “Four Cuts” affects locals by forcing them to leave due to land seizure, forced labor, arbitrary taxation, and other forms of punishment that make it impossible for locals to sustain a livelihood in their home areas. Though the “Four Cuts” strategy had officially discontinued for a time, on March 4, 2011, the War Office in Naypyidaw ordered the reinstatement of the “Four Cuts” campaign[6]. The gas pipeline expansion and construction of new roads is one method of ruining villagers livelihoods and forcing locals to move out of their homes.

A document collected on March 5th, revealed that during the construction of the new pipeline route in Mudon Township, at least seven villages lost between 200 and 400 acres of paddy land or rubber plantation land. As claimed by Nai Tun Nai, a 55-year old farmer from Set-twe village, it is more likely that more land will be ruined. His own paddy land has already been devastated:

About two of my four acres of land were ruined. The team who constructed the pipeline made a line with bulldozers [through it] without asking my permission…a fifteen foot wide [strip] of my two-acre land was all destroyed, though I begged [them not to do so], but they replied that they were acting according to higher officials’ orders. I already lost two acres of my six acres of land during the land confiscation for the pipeline in 2002. Now, about two acres of my land has been included [in this confiscation]. What’s worse is that that land is paddy threshing ground[7]. To whom do I have to report? Like my own land, Ko Thein Tun’s land was also bulldozed.[8] His paddy land is now separated into two parts because the digging was done in the middle [of his land]. Another plantation owner’s [land] has also been ruined. No compensation was provided [in any of these cases].

Nai Seik Rot, a farmer living in Yaung-daung village, Mudon Township, provides the details of how his 1.8 acres of farmland was destroyed by the government project of reconstructing the Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline.

To repair the pipeline, they, a group of government engineers, came to check out my farm often. That was in November 2010 [when they came to check]. When the time came to install the new pipeline, they did not dig up the old pipeline. Rather, they measured another new route which is 7 ft. from, and parallel to, the old pipeline route. When we asked them what the measurements were for, they replied that it was for the new gas pipeline route. It is estimated that 1.8 acres of my farm is measured for the new route. Because they drive in their excavation machines through my paddy fields. The path leading through paddy fields is one of destruction. My farmland is destroyed when those excavation machines drive through.

Nai Seik Rot added that the installation of the new gas pipeline has included the seizure and subsequent destruction of 48 acres of farmland, belonging to 18 Yaung-daung villagers. He further explained that 50% of the farmers whose farmland was used for the previous pipeline installation in 2001 has now been destroyed for a second time.

Eyewitnesses explained that not only valuable paddy land, but also the rubber trees on which locals rely, were lost due to the re-extension of the pipeline. Three of the interviewees estimated that in Thanphyuzayat Township alone, almost 100 acres of rubber plantation were appropriated for the pipeline expansion. Rubber cultivators estimated that at least 4,000 rubber trees were lost. Additionally, most of the rubber cultivators who just lost their land had already been impacted in the 2000-2001 pipeline construction.

An interview in early March with Min Tin Thun [above]’s fellow villagers, U Kyin Phay, Daw Ma Myo, Nai Kyaing, Daw Ma Than, in Northern Ye Township, documented an additional loss of 80, 66, 120 and 300 rubber trees respectively. All of these plantation owners individually lost between two and four acres of land due to the order of the Ye Town Peace and Development Council (TPDC) for the first extension of Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline ten years ago. U Kyin Phay, 61, a former school teacher and a resident of northern Ye Township, Mon State:

An interview in early March with Min Tin Thun [above]’s fellow villagers, U Kyin Phay, Daw Ma Myo, Nai Kyaing, Daw Ma Than, in Northern Ye Township, documented an additional loss of 80, 66, 120 and 300 rubber trees respectively. All of these plantation owners individually lost between two and four acres of land due to the order of the Ye Town Peace and Development Council (TPDC) for the first extension of Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline ten years ago. U Kyin Phay, 61, a former school teacher and a resident of northern Ye Township, Mon State:

On one hand, the land we live on is under the rule of law [living in Burma, which is a government that has laws by which it rules]. In everything there should be an explanation of cause and effect. We should receive protection by the laws set in place. Now we have to, for a second time, lose our property again due to this pipeline issue. We know again that we can’t report to anyone. The person who [oversaw] the digging of the land said that he is just a civil servant and that he has to do as he is instructed so ‘please try to understand’ him. Currently, we have been planning to report [this case] to the chairman. There is a hierarchy so the highest is the State president.[9] The process is done and the trees are already ruined, but we want to get fair compensation [for this loss] because we rely only on these trees for work.

Unlike the previous quotes by villagers’ whose land has been requisitioned, U Kyin Phay expresses a desire to use the political rights afforded him and make a plea to the recently elected government. His wish to take action is echoed in interviews with villagers from Mudon Township. According to the information from the field, of the three townships, Mudon Township, in which MOGE is constructing a new route instead of remodeling, is the most impacted by the Kanbauk-Myaing Kalay gas pipeline. An anonymous observer from Mudon Township explains:

The land was continuously impacted from the Thanbyuzayat exit – Phaung Sein, Kwan-Hlar, Yong-Don, Hnee-Padaw, Set-Twe, Doe-Mar and Kalogtot to Kamawet. Some areas more so than others. Because they didn’t re-excavate the old pipeline. They left (the old pipeline) in its original state and made the new pipeline route in a different area. Therefore, the new paddy land was impacted. Like us, the villages before Mudon and in Kamawet were also impacted. To whom do we have to report?

Repeating the desire to report the abuse of land confiscation, Nai Myint Win, a Naypyidaw villager and farmer, who is 40 years old, reflects on the loss of farmland from the pipeline installation in Mudon Township:

I do not think that we can ask [MOGE] to dig out the pipeline, stop this gas pipeline project, and give our farms back to us. They, the government, have never responded to what we request. What is possible for us to hope for is to get fair compensation [for our lost land]. We ought to ask them, the government, for the compensation of our destroyed farmland so we can set up other businesses. There are some of us whose farmland was taken over during both the first installation of gas pipeline and second installation of pipeline while others only had their farmland taken during this second time. Because of the loss of our farmland, it can affect our livelihood, and it would be much better for us if the central government considers giving compensation for our farmland after sending a petition letter with our signatures to them. Therefore, now we want to approach the All Mon Regions Democracy Party (AMDP)[10] to talk about this.

Though many villagers were united in wishing to make a case for their land loss, they also voiced worry at the repercussions for doing so, such as the possibility of being charged and punished by the government, with the possibility of jail time. Nai Ni, a Ni-pa-daw villager, who currently lives in Sat-twe village, on March 10th :

If they [send the petition] the government could make things worse; they will charge us with any punishment. And they will charge us because of writing the letter by using a computer – that is what is said under the electronic section[11]. Worse yet, if we signed the petition letter, it will interrupt the government project, and as a result, we will be charged under another punishment or one more section. Consequently, we will not only lose our farmland but also be jailed. That is what we worry most about. For me, I will believe that that happens because of our misfortune or bad-luck rather than saying anything.

In Mudon town, Mon Buddhist monks and educated youths are making an effort to gather together the farmers who lost land and to become organized. A young Mon Buddhist monk who is studying Pali[12] at a monastery in Mudon town, reported that his relatives are also facing many difficulties due to the gas pipeline project. He is hopeful that the new government, which began on April 1, 2011, will help right some of the wrongs inflicted upon the villagers, such as land seizure:

At the moment, because of this gas pipeline project, everyone is thinking about how to sort this problem in a way that can satisfy them [the farmers], including my relatives. What I’m thinking is that we have to get the list of the amount of farmland that’s been destroyed or taken over, and we can report about this, with the list, to the new government operating in Mon State. Also, since there is our Mon Party – the AMDP – with their help, we can solve this problem. I think, we might be compensated for our farmland. Also, we have got to request [the government] to stop taxing and oppressing us as we have been levied and suppressed by the government for 10 years. To say what is obvious, since this gas pipeline project started, the civilians living along the pipeline have not gotten any electricity access [since the gas pipeline project started in 2000, villagers in that area do not have electricity], nor has anyone even gotten a penny. Rather, everyone has suffered and faced many difficulties.

Analysis & Conclusion

Repeated in all the interviews conducted for this report, is the fact that all interviewees, whether they are cultivators or landowners, have suffered from the reconstruction and expansion of the gas pipeline running from Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay. In fact, villagers living near the pipeline have been suffering since the first construction, which began in 2000. The first construction involved the excavation and placing of roads that very often passed right through paddy fields, rubber plantations, and even people’s homes, destroying many villager’s livelihoods. These violations against the villagers during the first construction never resulted in adequate compensation or, in most cases, compensation of any kind. Most villagers had to re-setup and replant their paddy or rubber trees in order to sustain a livelihood in their village.

Now, the re-expansion of the pipeline, which includes new roads in some areas, once again does not take into account the areas in which villager’s homes and landholdings are situated. Once more, villagers are subjected to disregard and roads are dug straight through their fields, devastating their crops and sources of income. Most villagers are already living in subsistence levels, so the annihilation of their livelihoods has resulted, for at least one person mentioned in this report, in needing to leave his home village and find work in order to survive.

Now, the re-expansion of the pipeline, which includes new roads in some areas, once again does not take into account the areas in which villager’s homes and landholdings are situated. Once more, villagers are subjected to disregard and roads are dug straight through their fields, devastating their crops and sources of income. Most villagers are already living in subsistence levels, so the annihilation of their livelihoods has resulted, for at least one person mentioned in this report, in needing to leave his home village and find work in order to survive.

It is important to note, however, that while villagers received no compensation during the first construction ten years ago, some villagers interviewed in Mudon and Thanphyuzyart Townships stated their desire to seek compensation this time around. Whereas in the past, experiences of the human rights abuses committed by the Burmese government against the villagers had taught villagers not to seek retribution for these crimes, many have become aware of the possibility to help themselves.

There are two possible reasons for why villagers now dare to make a claim for land loss. One is the appearance of Community Based Organizations (CBOs) throughout ethnic villages. Before the pipeline construction, there were only health organizations, but in the past ten years, other organizations such as monk associations, youth associations, literature and culture associations, skill clubs, and farmers associations have materialized throughout the villages. Though many of these associations carry out their purpose in accordance with their title, it is through these CBOs that villagers are able to receive outside information as well. In addition, the National League for Democracy (NLD), the leading democracy party in Burma, which boycotted the November 7th elections, has also sent lawyers to villages who are capable of working on human rights abuse cases.

A second reason for an unaccustomed boldness amongst villagers may also be a result of the nationwide elections that took place on November 7, 2010 for the first time in 20 years. Though the elections have been dubbed fraudulent by most international powers and also by many inside Burma, the knowledge that a new government is in place and that the ethnic Mon people have representatives in the form of the AMDP, has elicited a way in which villagers can make their claims heard. Those villagers who announced that they plan on writing a petition for land compensation also mentioned that they now have a political body in Mon State to represent them and their needs.

Even with the implementation of a new government, laws enacted before the new government took effect are still applicable and enforced. This means that if villagers muster up the courage to petition and inform the Mon State government about the land confiscation abuses, it is still highly likely that government officials will use laws such as the Electronic Transactions Law to penalize those villagers who report on the human rights abuses. It is important, therefore, for those CBOs present in the villages to take notice of the land confiscation and abuses committed against villagers living near the gas pipeline. Additionally, it will be crucial to take note of how the new government deals with abuses inflicted upon villagers by government owned companies, if the abuses will decrease or remain the same.

[1] Paddy is a field where rice is grown.

[2] p. 43-46 in Laid Waste details the pipeline explosions, and villagers views of the causes for the explosions.

[3] Laid Waste specifies that “battalions responsible for the pipeline have seized more than 12,000 acres of land as welll as demanded daily support from local villagers… ‘pipeline battalions’ have also been responsible for a raft of violent abuses including torture, murder and rape.” (2)

[4] Residents living nearby pipelines that are leaking, or have ruptures, are forced to pay the damages and the price of the leaked gas. Please see HURFOM’s July 5, 2010 report, We All Must Suffer: Documentation of Continued Abuses During Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay Pipeline Ruptures (http://rehmonnya.org/archives/1492).

[5] Area where farmers collect harvested paddy and do the threshing to release the rice from the husks.

[6] Please see the Irrawaddy’s article, “Naypyidaw Orders New “Four Cuts” Campaign,” by Wai Moe. http://www.irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=20880

[7] harvesting ground – the paddy has already been gathered and is ready for releasing the rice “seed”.

[8] a paddy land owner whose land is adjacent to his farm.

[9] They will submit their case to the chairman of Mon state.

[10] The All Mon Regions Democracy Party was the sole Mon party to participate in the nationwide elections that took place on November 7, 2010. Out of 34 positions in Mon State, AMDP won 16.

[11] On April 30, 2004, the Burmese government instated The Electronic Transactions Law Electronic Act (SPDC Law No:5/2004) which allows the Burmese government to charge citizens with violations such as using the computer to write a petition against the government, etc. A breach of the Electronic Act can result in 7 to 15 years jail time and a fine. The term can also be extended five years. Please see Inter Press Service’s article, “Junta Turns to Draconian Electronics Law to Silence Critics,” by Marwaan Macan-Markar. http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=49933.

[12] The language used in the original documents of Theravada Buddhism.

Comments

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.