“They will burn the village until it turns to ash”: Gross human rights violations committed by LIB Nos. 562 and 563 in Kawkareik Township, Karen State

June 13, 2011

On the morning of January 13, 2011, the Burmese Army’s Light Infantry Battalions (LIB) No. 562 and 563 entered Dauk Phalan village in Kawkareik Township, Karen State. Unbeknownst to the LIB troops, Karen National Union[1](KNU)’s Brigade 6, battalion No.18, was present in the village. Coming upon each other, both sides opened fire. During the fighting, sections of the LIB battalions scavenged the village for residents they believed to be linked with the KNU. LIB troops then conducted arbitrary arrests of accused rebel supporters, inflicted physical punishment upon villagers, forcibly took villagers to work as porters, and destroyed the properties and livelihoods of villagers in order to insure armed ethnic groups were unable to survive in those areas. Download report as PDF [217KB]

LIB Nos. 562 and 563 are known by Dauk Phalan villagers as the Rakhine Battalions. They are commanded by the central Burmese government in Nay-pyi-daw, but more directly commanded by the Military Operation Management Command (MOMC) No. 5. These two battalions were formed to conduct a military offensive against a breakaway faction of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army[2] (DKBA)’s Brigade No. 5 led by Colonel Saw Lah Pwe. On November 7, 2010, Burma held nationwide elections for the first time in 20 years. The following day, fighting broke out between Saw Lah Pwe’s renegade group, who split with the DKBA after factions of Brigade 5 agreed to become part of the Burmese-run Border Guard Force[3].

Saw Law Pwe is currently the leader of the Kloh Hto Baw command. He and his command have been engaged in conflict with the Burmese army since November 8th, constantly moving throughout the townships of Karen State. Currently, Saw Law Pwe’s Kloh Hto Baw command and KNU’s Brigade 6 cooperate with each other. More often than not, the presence of a rebel armed group [DKBA or KNU] creates conflict and insecurity for villagers, often leading to violent outbreaks between Burmese battalions and whichever armed group is in the area.

In the last week of December 2010, the Rakhine battalions marched through many villages on their way to Wal-Lay village, Kawkareik Township, Karen State. In this report, HURFOM exposes interviews that document the human rights abuses caused in the villages through which the Rakhine battalions passed. Those interviewed by HURFOM were victims, eyewitnesses, village chairmen, and observers of the current conflict and situation. Some were interviewed for their special knowledge on military affairs in the area, are government appointed, or linked with rebel groups.

The following are accounts of the commission of crimes against humanity catalyzed by fighting between the Burmese troops and ethnic-Karen armed groups. Accounts reveal village closures (travel and movement restrictions) due to fear of landmines as well as village ambushes in which Burmese troops conducted offensives against ethnic rebel groups. The intense fighting between Burmese battalions against the DKBA and KNU made it impossible for HURFOM’s field reporters to travel near the afflicted areas. Not until April did it become safer for field reporters to collect in-depth interviews in limited areas. Still, the continued presence of both Saw Law Pwe’s command and the KNU creates ongoing conflicts. HURFOM was therefore only able to collect a limited sample of accounts. Human rights violations are ongoing, yet it is currently impossible to reach the victims of those human rights abuses.

Interviews for this report were collected in Kawkareik Township, Karen State, between April 1st and April 30th.

Torture

Dauk Phalan village in Kawkareik Township, Karen State consists of 100 households. The majority of the residents are ethnic Karen and depend on farming for their livelihoods. This village is located in a KNU Brigade 6 area of control. And because the KNU and the Burmese army have been in conflict documented for the last two decades, the area in question is prone to human rights violations committed by Burmese troops against villagers. The Burmese Army considers areas under KNU control to be “free-fire” zones[4].

During the conflict on January 13th, troops from both battalions separated; while some were engaged in fighting, others searched the village for informers and supporters of the rebel groups. Villagers accused of being in contact with ethnic Karen armed groups were arrested and beaten by Burmese troops, forced to serve as porters and watch the destruction of their own homes.

During the conflict on January 13th, troops from both battalions separated; while some were engaged in fighting, others searched the village for informers and supporters of the rebel groups. Villagers accused of being in contact with ethnic Karen armed groups were arrested and beaten by Burmese troops, forced to serve as porters and watch the destruction of their own homes.

The morning of January 13th, Captain Aung Lin and 20 troops from LIB No. 562 and 563 arrested an ethnic Karen villager in Dauk Phalan by the name of Saw Thein Bal. He was 18 years old and a deaf-mute. Saw Thein Bal was arrested along with his father, Saw Maung Sar, and mother, Ma Kyi Nyut. He and his family were accused of being spies for the KNU. Saw Thein Bal’s parents were detained but not tortured. On April 22nd, Saw Thein Bal’s older brother asked him, through a family-understood sign language, to explain what happened:

I did not know about the fighting. On that day, I went to my relative’s wedding in Dauk Phalan village with some of my villagers, but none of us knew anything about the fighting. When we were on our way to Dauk Phalan village, suddenly a group of Burmese troops surrounded and tried to arrest us. As it happened immediately, I tried to escape, but because they surrounded me, I could not run away and I was arrested. I was very frightened when I looked at their faces. But, it was hard to interact with them using my legs and hands [trying to sign using body language]. Then, they made me kneel down on the ground, and three soldiers kicked my back and head with their soldier’s boots several times. Having kicked me for five minutes, their leader said to stop [kicking me], and at the time, I noticed my head had begun to bleed. In the beginning it was very painful, but after many times, I didn’t feel much. Then, I was taken with them. I was aware that they took me by way of Kawkareik town, and when they were marching forth, I had to walk in front of them[5].

Saw Thein Bal proceeded to explain that two days later, on January 15th, the troops arrived at a military base near Kawkareik Town. There, Saw Thein Bal was asked questions about the KNU. Believing Saw Thein Bal to be feigning ignorance by using his hands and legs to sign, LIB troops beat and kicked him in the back repeatedly:

At that military station, four soldiers who seemed as old as I am, punched me and beat me with sticks. As far as I remember, they hit my face with a gun barrel, besides swearing at me, and they hit my face hard. Then, they hit my nose and forehead with the gun barrel again and questioned me in Burmese. When I answered using my legs and hands, they replied that they didn’t understand anything. Whenever I answered, they got angry at me. After that, two other soldiers came over and punched me, and because I couldn’t say anything, I was just beaten up.

Saw Thein Bal’s older brother explained that the Burmese troops did not realize Saw Thein Bal was actually deaf-mute until they arrived in Kawkareik:

Saw Thein Bal’s older brother explained that the Burmese troops did not realize Saw Thein Bal was actually deaf-mute until they arrived in Kawkareik:

They [the army] did not know that he [Saw Thein Bal] can neither speak nor hear and they thought he was pretending not to know anything. After, we, the entire family, found out from sources from the village, that my younger brother was arrested by the Burmese army in Dauk Phalan village and taken to Kawkareik [Town], we headed there. Highly concerned, we tried to find out about him. Because my younger brother is kind of disabled, we, the family, were so worried about him. We finally heard that my younger brother was detained at the military barracks outside of Kawkareik Town, which was after he had been detained 18 days. We found out that my younger brother was arrested by the Burmese troops because they thought he was from the KNU. After finding that out, I hurried to my village, calling on elders in our village and my parents. While I was hurrying to the village, which took half a day, we heard that my brother, Saw Thein Bal was taken over to Kaw-saik village with the army. After knowing that my brother was taken to Kaw-saik, we headed to the temporary front-line base in Kaw-saik. We went to meet the officer of LIB No. 562 at the [military] station in Kaw-saik. Then, we negotiated with the officer, explaining to him that my brother is deaf-mute and he is not from the KNU. They, the army, did not believe what we told them, and finally, we had to negotiate with the village head and as a guarantee [an exchange or unofficial bribe] we gave them 200,000 Kyat[6]. In exchange for my brother, we had to borrow 200,000 Kyat from our relatives. After he was released, we saw that my brother was wounded; with lots of cuts and bruises. Now, after four months, he does not seem to have any cuts or bruises. Yet, he is still agonized by his experience.

As an act of revenge, Saw Thein Bal told his brother that he now wishes to become part of a rebel group and fight against the Burmese army. At the moment, Saw Thein Bal is in Lan-pan village, Kawkareik Township, living with his family and working on the farm. Saw Thein Bal’s family is still 200,000 kyat in debt because they have not been able to pay the sum back to their relatives. The family has expressed concern for their present survival.

As an act of revenge, Saw Thein Bal told his brother that he now wishes to become part of a rebel group and fight against the Burmese army. At the moment, Saw Thein Bal is in Lan-pan village, Kawkareik Township, living with his family and working on the farm. Saw Thein Bal’s family is still 200,000 kyat in debt because they have not been able to pay the sum back to their relatives. The family has expressed concern for their present survival.

According to villagers living in Dauk Phalan, Saw Thein Bal’s experience is not uncommon. Since 2004, villagers estimated that there have been 50 cases of torture and no less than five have died by the hands of Burmese troops. The Burmese Army’s paranoia about ethnic armed groups in territories where the Burmese Army is unfamiliar has resulted in numerous human rights abuses against locals. Residents become victims of the Burmese Army’s ignorance solely for living in those villages. In these instances, most acts of torture result during questioning by the Burmese army about rebel groups’ whereabouts. According to the Lan-pan village chairwoman, who wished to remain anonymous[7], 39, an estimate of 50 would be low, especially because there is a lack of written documentation on human rights abuses that have been ongoing for decades. She confirmed that whenever the Burmese army goes into battle with other armed groups, civilian torture was always conducted by the Burmese army.

If we made an account of just the villagers who were punched once [by the Burmese Army], it would be countless…Also, some innocent villagers were killed due to the fighting between the Burmese troops and their opponents. After causing these cases to happen, there has never been any action taken [no justice], and still remaining victims suffer.

Execution

On January 16, 2011, DKBA battalions No. 908, and Unit 4, Battalion No. 18 of KNU’s Brigade No. 6, began to fight with the Burmese LIB No. 563 in Lan-pan village, Kawkereik Township. The fight lasted an hour, and afterwards the Burmese army forcibly entered the house of U Maung Myain, living with his three daughters and one son, Saw Kaw-lar, who is 46 years old. LIB No. 563 arrested Saw Kar-lar, took him to the woods, three miles from Kaw-saik village, tied him up with a rope, gagged his mouth with cloth, stabbed his back with a dagger, and executed him. At that time, one Kaw-saik villager, Saw Gae, who is 32 years old, was serving as a porter for LIB No. 563. He witnessed the execution of Saw Kaw-lar and met with a HURFOM field reporter to give his account:

That was in the afternoon, on January 16, 2011. Tying him up, they, the LIB No. 563, took Saw Kaw-lar over with them. That’s when I was in Kaw-saik village together with the troops, serving as a porter [carrying equipment and materials for the LIB troops]. Together with me, there were 12 other villagers ordered to porter. I would be very upset to keep on talking about this killing of Saw Kaw-lar. I feel very affected because I saw that incident with my eyes. Taken to their base, the troop commander and his fighters, tied Saw Kaw-lar’s hands and to get his mouth closed, they tied it with a red-colored cloth. Then, they forced him to kneel down and they cried out – swearing at him and accusing him of being a KNU supporter. After that, they started stabbing his back, into his lungs, with a dagger. After stabbing him several times, Saw Kaw-lar died right there. It was very scary. Still, I can’t get that picture out of my eyes. I became very worried right away, by thinking that likewise, we, the porters, will be killed whenever they want to kill. Since that time, I thought, for me, if there was a chance for me to escape from this serving as a porter, I would try.

According to Saw Gae, the LIB No. 562 and LIB No. 563 fought against unit 4 of KNU Brigade No. 6, Battalion No. 18 and the breakaway DKBA’s, Battalion No. 908. LIB No. 562 and LIB. No. 563 included 80 troops and marched to Wal-lay village with 50 porters.

According to Saw Gae, the LIB No. 562 and LIB No. 563 fought against unit 4 of KNU Brigade No. 6, Battalion No. 18 and the breakaway DKBA’s, Battalion No. 908. LIB No. 562 and LIB. No. 563 included 80 troops and marched to Wal-lay village with 50 porters.

Saw Gae did not personally know Saw Kaw-lar because they lived in neighboring villages. He escaped from forced portering on January 18th after pretending to go to the bathroom, but instead running away.

I was very sad when I told his wife [who is 38 years old] and his three children about the killing. I can’t imagine how hard life is going to be for her with her three children. Now, Naw Htew Tay seems like she is out of her mind… Not knowing why and how one Burmese soldier did so, she showed me a cut that was made on… her son’s right shoulder.

With Saw Kak’s help, the HURFOM field reporter met with Naw Htew Tay, Saw Kaw-lar’s wife, and was able to interview her for the full story:

Everyone knows that apart from ordinary villagers, my husband did not befriend anyone [any ethnic armed group]. He did not even have contact with any armed groups. So, why did the Burmese troops kill him? That’s not fair. They are the ones who went into the battle but now the person who got killed is my husband. They are the persons who should get killed: not my husband. Now, I have my three kids and have no skills to work. Now, I do not know what to do as I can not afford sending my three kids to school and there is no rice left at home to cook.

The military’s use of extrajudicial killings not only inflicts fear upon the local villagers, but directly causes families to suffer financially. The loss of her husband, the only skilled worker in the family, turned Naw Htew Tay’s family from surviving to living below subsistence levels.

Relating back to the porters with which Saw Gae had been grouped, Saw Gae, who was also punched during his term as a porter from January 15th to 18th, explained that he did not know in what condition the other 12 porters were:

There is one thing that seemed a bit strange. On January 17th, the day Saw Kaw-lar died, the Burmese LIB No. 563, which was transferred from Rakhine State, met up with LIB No. 562, the battalion using me as a porter, on the way to Wal-lay village. Along with LIB No. 563, there were 50 porters from central Burma, and I found out that these troops are not only using us to serve as porters but also others from central Burma. Now, if I hear that there is an army seen from far away, my back begins to feel cold. Anyone would be frightened if they witnessed what I witnessed. Now, at this present place, I do not dare to live here because there is no safety.

Saw Gae’s observance that many of the porters were from central Burma should be noted. Most documentation involving Burmese civilians being used as carriers or porters takes place near the eastern Burma border and involves the use of ethnic minorities, such as the Karen.

Extortion

Burmese troops from LIB No. 562 and 563, under MOMC No. 5, demanded payment for the cost of army supplies and medical assistance for the troops from residents living around Kawkareik Township. Furthermore, Burmese troops arrested villagers in order to demand money for their return home. The Lan-Pan village chairwoman explained:

As described before, to get Saw Thein Bal released after he was tortured, his family had to pay 200,000 Kyat. That’s the amount of kyat given by only one household. In Lan-pan village, starting in January and still ongoing, the Burmese army has demanded money from villagers many times. For example, at the end of January, to provide medical aid for wounded men and porters, we were ordered to collect money, and totally, we from the whole village had to pay 200,000 kyat. As there are about 100 households in the village, we collected from each household and paid the Burmese Army. And, in the first week of March, Unit No. 3, under the MOMC No. 5, demanded from us, the Lan-pan villagers, 200,000 kyat for their army rations again, since they do not often station in Wal-lay village. That time also we [had to] collect money from each household in our village and pay as they demanded. It is also possible that the Burmese army overcharged villagers from other villages for money, but we do not know about that because we have not been informed. Yet, if we had known about that [other villagers were demanded to pay], we could not help them give money. This is because we have to struggle for our daily meals while the situation in the region is unstable.

Two months later, in early March, residents of Ah-son village, which holds 200 households, were forced to pay 250,000 kyat to LIB No. 562 and LIB No. 563. One Ah-son villager, who is 44 years old, explained:

Our village head, Saw La-nay, who is 48, came to collect money from every household. Some villagers gave 3,000 Kyat, and some gave 2,000 Kyat to him. Collecting from each household, a total of 250,000 Kyat was collected and given to the Burmese troops. We can not refuse giving as they [Burmese troops] demand it. The village head also said that he could not pay for us like before anymore. We also have to pay by borrowing from others. Our village head said that he came to collect the money to provide for the Burmese army’s rations. They have collected money like that many times: since the DKBA from this region and Burmese troops engaged in the fighting. And, we have to pay just like this.

Not only did Burmese troops demand money for their own rations and medical assistance, lacking proof, these Burmese troops also arbitrarily accused villagers of being supporters of the KNU and breakaway DKBA and providing these rebel groups with shelter. This was confirmed by Saw Taung Kyi-myain, who is 47 years old, and works as a farmer:

Accusing people of having contact and supporting members of armed groups from the jungle, the Burmese troops also demanded money. They caused a problem with not only a household but also the whole village and then ask for money to fix it. Before the Thingyan water festival [the Burmese new year], in March, the troops, transferred from Rakhine State, came to Ah-son village to collect money. There are seven quarters and 200 households in the village. They collected money as ‘fines’. The charge was to accuse us of supporting armed groups from the jungle while they said that ‘if you, the villagers in this village, support the armed groups from the jungle, you all also have to support us,’ and they demanded 1,000,000 kyat, but after the village head apologized and asked to reduce [the price], the demand decreased to 500,000 Kyat. For that demand, we, our family alone, had to pay 2,500 Kyat, but for those who do not have money to give, the village head, Saw La-nay, had to pay for them. The village head also can not afford [paying the sum]. And the village head has said for a long time that he does not want to serve as village head anymore. … ‘Having to pay on other’s behalf, who wants to be village head?’

Saw Ka-lae, who is 30 years old and resides in Kaw-pain[8] quarter, recounted how the Burmese army demanded money and how those who could not pay would be punished:

Who can live here without paying as they, the Burmese Army, demand? For instance, if we do not give as they ask, as they are bad, they will get angry at that whole family and will accuse them of being supporters of rebel groups and then make problems with them. Yet, even worse, they will burn the village until it turns into ash. If they want, they can do that easily. For them, here is their front-line [of battle]. We all know that they can do whatever they want. So, we cannot do anything, even though we have nothing to feed our kids, for them [the Burmese army], we have to find and give as they demand. This is because we are afraid of them.

Saw Ka-lae shows that severe punishments by Burmese troops cause villagers to succumb to the extortion exacted upon them.

Property Destruction

On the morning of January 16, 2011, during fighting between the Burmese troops from LIB Nos. 562, 563 and 543, KNU, and the breakaway group of the DKBA, villagers’ houses and properties were destroyed and looted by the Burmese troops in Lan-par village, Kawkareik Township, Karen State.

On the morning of Jan.16, 2011, after the Karen armed group withdrew, Sergeant Nay-lin led a group with eight fighters into Lan-par village, Kawkareik Township. Eyewitnesses saw the troops enter the houses of those villagers who had fled the fighting and took useful household materials and other easily portable properties. As for the heavier properties, the troops destroyed them. One Lan-par villager recounted:

On the morning of Jan.16, 2011, after the Karen armed group withdrew, Sergeant Nay-lin led a group with eight fighters into Lan-par village, Kawkareik Township. Eyewitnesses saw the troops enter the houses of those villagers who had fled the fighting and took useful household materials and other easily portable properties. As for the heavier properties, the troops destroyed them. One Lan-par villager recounted:

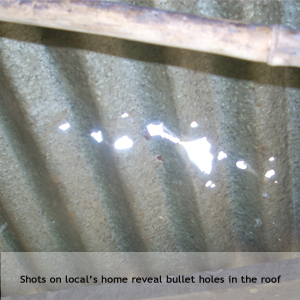

When the village becomes a battlefield, there are a lot of houses left behind[9]. Then, the Burmese troops entered the houses left alone, and picked up every belonging that they found while they also damaged some belongings. I saw them doing that while I was hiding in a paddy-barn. Especially [affected] was my neighbor’s house, Saw Maung Sein’s house, which a Sergeant went into with four men and shot off gunfire. At the time, I could only hear the sound of gunfire as no one can come out. Later, after they withdrew from the village, we find out that they shot the wooden box of Saw Maung Sein’s wife until it opened and took the 30,000 kyat, which had been saved from selling beans, as well as two army-style warm-coats. Also, they shot the roof of the house, and broke the water-pot, in addition to shooting plates and bowls, kitchen utensils randomly, leaving everything useless.

HURFOM also found out that Lan-par villager, Maung Taing-yee’s pig was shot by the Burmese army and carried away to be eaten by the Burmese troops. Maung Taung-yee, who works as a farmer for a living, recounted:

My pig weighed 40 kg. We only knew that our pig was taken away after the fighting was over when we returned to our home. When we got inside the home, we saw our closet shot while our plates and bowls were damaged. As we are poor, we have nothing, so they can’t take anything, but they took our pig.

Burmese troops also destroyed one Cordless phone, one Receiver, and Sanyo (point & shot) camera belonging to Saw Pan-lay, who is 29 years old, and Mg Taing-yee’s neighbor. The value of his destroyed property was over 700,000 kyat:

Before, I used to run a local phone service business and I owned a cordless phone, but the cordless phone together with its machine [receiver] and 12 volt battery were shot and damaged. … I stopped working as phone operator as security got worse. And my camera which I used to take photos at donation celebrations and hired at festivals. But now, it’s also gone.

Saw Ohm Sein, who is a 55 year old farmer reported that the roof of his house was shot as well as his paddy-barn built at the back of the house. Surprisingly, his 50 packages of paddy [uncooked rice] were left untouched.

Destruction of villager’s properties is part of the Burmese government’s Four Cuts Policy. According to the Network for Human Rights Documentation – Burma, this policy was originally instated in the 1970s. The purpose of the Four Cuts policy is to cut off rebel groups access to food, funds, information, and recruitment[10]. Effectively, this policy not only negatively affects rebel groups, but the locals who live in those areas as well.

Conclusion

Due to ongoing conflict, which makes entrance into certain villages and conflict zones basically impossible, HURFOM was only able to collect a small sample of interviews. In fact, the human rights abuses mentioned in this report are occurring throughout Kawkareik Township. According to the United Nations, these human rights violations committed against civilians by the Burmese Army fall within the designation of crimes against humanity: torture, execution, and persecution of a group based on its ethnicity.

Based solely on Burmese troops’ uninformed suspicions, villagers become victims of torture, repeated questioning and detainment, and even execution, with no venue for which the abused can defend themselves. Burmese troops are not held accountable for the actions they take against civilians in ethnic villages and there is no recourse for which the villagers are able to seek justice.

Similarly crippling to locals caught between rebel groups and Burmese Army conflicts is the destruction to locals’ homes and the taxation meant to support the Burmese Army. Yet, the Burmese Army’s methods of taxation and extortion are conducted without transparency, leading many locals to be overcharged, which occurs when there is no documentation system for those who have already paid.

The lack of accountability with which the Burmese government has conducted its affairs for the last twenty years assumably should have changed with the switch to a new government in April 2011. Unfortunately, those who were interviewed three months after the events took place, said, that in April, even after the government changed, abuses continued. This is evident by the fact that military offensives by the Burmese troops are ongoing in Karen State.

Saw Law Pwe, the commander of the Kloh Hto Baw command, is currently living in Palu village, Kawkareik Township and with his presence comes the entry of more Burmese troops into the area. Saw Law Pwe’s continued ability to catalyze military offensives by Burmese troops into the rule of the newly instated government clearly demonstrates that the Burmese government has not changed its tactics toward the ethnic areas near the eastern border. Ethnic villages continue to be pillaged and villagers continue to be tortured and executed by Burmese troops. In relation to ethnic minority groups living near the eastern Burmese border, the new Burmese government has continued acting discriminatorily, abusively and without accountability.

[1] The Karen National Union formed in 1947. Hoping for an independent Karen State, the Karen National Union has fought until now for independence. The Karen National Union controls certain areas of Karen State and is known by the Burmese government as an insurgent group. Www.karennationalunion.net.

[2] The Democratic Karen Buddhist Army is a rebel group that separated from the Karen Buddhist Army in large part due to religious differences. Though the DKBA has, in recent years, been an ally of the Burmese Army, the implementation of the Border Guard Force by the Burmese Army led some factions of the DKBA to break from the larger group.

[3] The Border Guard Force is a sub-section of the Burmese Army. It is intended to patrol ethnic areas, transforming former ethnic armed groups into militias serving the Burmese government. The Border Guard Force came into effect after the nationwide elections on November 7, 2010.

[4] “Free fire” is designated by the Burmese army and allows the Burmese army to deliver justice in the way it sees fit, firing indiscriminately in the “free-fire” zones.

[5] Oftentimes, Burmese troops force local villagers to walk in front of the battalions as a safety measure for the Burmese troops. Landmines are rampant throughout the conflict areas and the villagers are used as human land mine triggers. Please read HURFOM’s February 10, 2011 report, Like birds in a cage: Impacts of continued conflict on civilian populations in Kyainnseikyi and Three Pagodas area. http://rehmonnya.org/archives/1902.

[6] 200,000 kyat is equivalent to $246 U.S. Most farmers in Eastern Burma make 3,000 kyat for daily labor.

[7] For those readers that are interesting in knowing the name of the village chairwoman, please contact HURFOM individually. For her safety, her name has not been mentioned in the report.

[8] Some of the names of the quarters in the Ah-soon village are named in Mon as Mon people used to live there before. Those quarters with Mon names are Kaw-pwe, Kaw-pain, Kaw Ka-taw, Pain-nae, Tain-parain, and Som Pay-taing, and those are the quarters where the Burmese troops often come to demand for money.

[9] Villagers often flee when conflict begins.

[10] http://www.nd-burma.org/news/685-naypyidaw-orders-new-four-cuts-campaign.html

Comments

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.