In southeastern Mon State, the Military Junta is trying to stage a picture of “peace” that doesn’t exist. With its election only weeks away, the junta is pushing displaced families back into villages that were emptied by fighting, places like Chaung-Hna-Kwa, Hlwa-Sin-Gone, and Kyon-Kwe villages, in the southeatern Kyaikmayaw Township of Mon State, even though those areas are still contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells. Villagers are being told to return not because it is safe, but because the Junta wants the villages to look populated for the cameras. Behind that forced return, however, are all the real problems the junta refuses to fix: fields that can’t be farmed because of mines, roads and water sources that are too dangerous to reach, aid agencies blocked from helping, and families trapped in fear, poverty, and psychological stress.

A Manufactured Normalcy

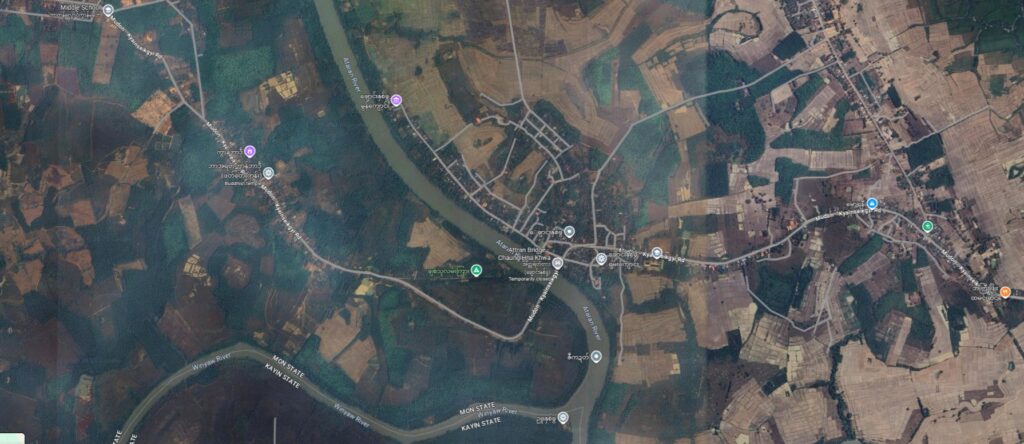

As the Junta prepares for the first phase of its so-called election in about 50 days, military units have begun pressuring families to move back to Chaung-Hna-Kwa, Hlwa-Sin-Gone, and Kyon-Kwe villages in Kyaikmayaw Township, areas that were nearly destroyed during heavy clashes in 2023.

Residents told HURFOM that they are being ordered to “repopulate” these abandoned communities so they appear normal for election observers and state media. Yet, beneath the soil lie deadly remnants of war, landmines, artillery shells, and UXO that no one has cleared.

“They say it’s safe now,” said a 38-year-old woman from Chaung-Hna-Kwa Village. “But we still see warning signs not to touch or step anywhere off the road. Soldiers told us to clean the village so they could take photos. It’s not about helping us, it’s about showing the world that their election areas are ready.”

Living with Invisible Killers

For the villagers of Kyaikmayaw, returning home now means living with constant fear.

Landmines and UXO remain active for decades after a conflict ends. They do not distinguish between civilians and soldiers. In Mon State, children have been among the most frequent victims, injured or killed while playing, farming, or collecting water.

“Every time I walk to the well, I am terrified,” said a woman from Hlwa-Sin-Gone Village. “My husband doesn’t let the children outside. We hear explosions sometimes from the fields. We live with fear every minute.”

A farmer from Kyon-Kwe Village echoed the same dread: “Two cows died when they stepped on something in the field. We came back because the army said it was safe. But it isn’t. We can’t farm. We can’t move freely. We feel trapped.”

Unseen Wounds: Psychological and Economic Toll

The physical danger is only one layer of the crisis. The invisible trauma is deep. Fear of explosions, the loss of homes, and daily uncertainty have caused widespread anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among villagers.

Entire communities are paralyzed. Landmine contamination has turned fertile farmland into no-go zones, creating food shortages and poverty. Many villagers are too afraid to return to their own land, while those who did now depend on borrowed food and money.

“The land is poisoned, not just by weapons, but by fear,” said a displaced farmer sheltering near Mudon. “We can’t plant rice or raise cattle. The land has become a graveyard for our future.”

The contamination also blocks access to schools, health clinics, and water sources. Damaged roads prevent humanitarian groups from delivering aid. And with telecommunications cut in many rural areas, villagers cannot even call for help during emergencies.

Humanitarian Neglect and Manipulation

Adding to their suffering is the junta’s deliberate obstruction of aid.

A 29-year-old humanitarian worker from Mudon told HURFOM that the regime continues to block independent CSOs, NGOs, and UN agencies from reaching those in need. Supplies are confiscated at checkpoints, and the army reportedly intends to use seized food and materials as campaign handouts to win political loyalty.

“The worst part is the lack of real humanitarian support,” he said. “More than 20,000 people in and around Chaung-Hna-Kwa urgently need help. Their homes are gone. Farmland is destroyed. But the junta won’t allow any real assistance. They’re keeping the aid and plan to use it for votes.”

This manipulation of humanitarian relief, turning it into a political tool, violates fundamental humanitarian principles of neutrality and impartiality.

The Hidden Costs: Social and Environmental Collapse

The consequences of the junta’s actions go far beyond fear.

The contamination has made large areas unusable for farming or construction, leaving families dependent on handouts or unsafe day labor. In some places, desperate villagers risk their lives collecting scrap metal from unexploded ordnance to sell, one of the leading causes of new accidents.

Meanwhile, toxic chemicals from explosives are seeping into the soil and water, threatening both agriculture and drinking supplies.

“We used to drink from the well, but now the water smells strange,” said a villager from Hlwa-Sin-Gone. “Even the animals won’t drink it anymore.”

Forced Return as Political Strategy

HURFOM’s field research shows that the junta’s forced-return campaign is part of a broader political theater to make conflict zones look stable before the elections. Soldiers are coercing villagers to return, warning that those who refuse could lose land rights or be labeled as sympathizers of the resistance.

These actions directly violate international humanitarian law, which prohibits the forced return of civilians to unsafe areas and requires the clearance of landmines before resettlement.

The junta’s propaganda of “reconstruction” is, in truth, a carefully staged deception, rebuilding for display, not for survival.

A Cry for Protection and Accountability

The situation in Kyaikmayaw represents a broader pattern across southeastern Burma: military control built on fear, coercion, and misinformation. As the junta turns dangerous villages into election showcases, it continues to sacrifice civilian lives for political legitimacy it will never earn.

“We are being used as proof that life is returning to normal,” said a young mother in Hlwa-Sin-Gone. “But what kind of life is this? We live among death.”

HURFOM calls for urgent international attention to the ongoing forced returns, landmine contamination, and weaponization of humanitarian aid in Mon State. Local communities need unhindered access to independent assistance, demining efforts, and mental health support, not more propaganda-driven suffering.