A Year Later, Villagers Still Displaced Unable to Return Home in Ye and Yebyu Township

May 23, 2011

Summary

In April 2010, the New Mon State Party (NMSP) refused the Burmese government’s request for the NMSP to transform into part of the Border Guard Force (BGF), in which it would essentially provide security for the Burmese government. Tensions between both sides rose because of the NMSP’s rejection and the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC – the former Burmese military government) began a recruitment project in local villages, forcing villagers to serve as militiamen and committing a variety of human rights abuses. During that period, HURFOM conducted interviews with local residents who fled their homes to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) sites, and documented the commission of crimes against humanity and assorted human rights abuses, on those IDPs, who lived in Ye Township, Mon State, and Ye Pyu Township, Tenasserim Division. Download report as PDF [270KB]

Villages that faced militia recruitment during this period were Alaesakhan village, Hlar-chaung-pyar village, and Ta-nee Tha-kyar village in Ye Pyu Township, and Ma-kyi village, in Ye Township. Villagers in these areas were confronted with execution, extortion, torture, and forced relocation by the Burmese Army [at that time, the SPDC], accused of supporting rebel groups, and used as human shields leading the Burmese army [SPDC]. Consequently, many of these villagers, along with their entire families, were forced to flee their homes, leaving their orchards and other properties behind.

Background:

Located on Burma’s eastern border, there are approximately 15 IDP camps. These camps are situated in Yebyu Township, Southern Ye Township, and Kyainnseikyi Township. The Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC)’s 2010 report, entitled, “Protracted Displacement and Chronic Poverty in Eastern Burma/Myanmar,” documents the effect of Burma’s increased policy of militarization and pressure on villagers living in former ceasefire areas to become part of the Border Guard Forces. Over 8,000 residents from Mon areas [including Ye Township] were reported to have fled from the army’s militarization efforts[1]. The report also estimates that by the end of 2010, there were over 500,000 IDPs living in Burma’s eastern border.

IDP camps, or sites, tend to look like very small villages, living in compounds, or in the middle of the forest. They mostly consist of 20 to 50 families, and because of their unstable situation, are forced to remain mobile, to evade army attacks, or to find more abundant food sources. Residents in these camps subsist by producing charcoal in the dry season, picking tall grass to make brooms, cutting bamboo for the production of a sticky rice dessert, and some grow hill paddy rice. Most of these jobs barely maintain subsistence levels and many children in the camps suffer from malnourishment.

Wishing to remain anonymous, one field coordinator, working with a Mon relief agency in the IDP areas, reported that IDPs were receiving no medical care. Mon relief agencies had begun to provide last resort medical aid. In Pa-nan-pon village alone, a Mon relief agency supplied aid to 500 IDPs, while in Kyun Pin village, 300 IDPs were given some form of medical assistance.

Speaking with one Mon relief agency, HURFOM discovered that one Pauk-pin-kwin villager and two Alaesakhan villagers were shot and killed after criticizing the SPDC’s militia recruitment project. SPDC troops based in Pauk-pin-kwin village forced villagers to relocate near a railway station, while residents in Khaw Zar sub-township were forced to construct the Village Peace and Development Council’s (VPDC) office and cover all the army’s expenses.

Additionally, villagers were forced to work as unpaid labor and serve sentry duty, and it has been reported that one group of villagers living under travel restrictions, when going out to sea to fish, had their boat shot by SPDC soldiers, and the villagers were forced to swim back to shore.

Unlike refugee camps, most IDPs are mostly forced to fend for themselves. In the past, IDPs received assistance from Mon relief agencies in the forms of cooking necessities such as rice, fish paste, cooking oil and beans. Only in emergency situations are some IDPs provided with limited health care.

The interviews documented in this report were taken by HURFOM field reporters between April 2010 to June 2010. Now, a year later, HURFOM has confirmed that those IDPs interviewed last year have been unable to permanently return home to their villages and are still living in the same situations inside the IDP sites.

Torture, Execution, Forced Labor and Extortion

The fear of arbitrary torture and executions is justified by the experiences of most villagers who have now become IDPs. Reportscollected through villagers from Alaesakhan village, Hlar-Chaung-Pyar and Ta-nee Tha-Kyar village in Yebyu Township as well as Ma-Kyi village in Ye Township documented instances of unwarranted torture and killings; one couple from Ta-nee Tha-kyar village was accused of letting a nearby rebel group gather in their orchard, tortured by the Burmese army, and then fined as a final punishment. Another woman whose nephew was forced to act as a human shield for the Burmese army, also experienced her husband being killed by the Burmese army, and a Ma-kyi villager was tortured for reporting news to the village head given to him by a rebel group.

Daw Yin, Ta-nee Tha-kyar villager, 56, on May 29, 2010 revealed why she and her husband were beaten by the Burmese army, and how much she was charged to pay as a fine:

We live here with only two of us: my husband and me. I moved to this village 5 years ago. Before, we lived in Chaung-Wa village. When we lived in Chaung-wa, the Burmese army did not allow us to stay there, instead we had to return to our home village immediately. Since then, we moved here [to Ta-nee Tha-kyar village].

We still go to work in our orchard. But, last year [2009], the Burmese army called the village headman and asked who the owners of the orchard, in which the rebel group was gathering, were. That orchard was mine but we were at home and did not even know that the rebel group was there. But, because of that, we were beaten and had to pay a 100,000 Kyat fine.

On June 21, 2010, Nai Mon, Alaesakhan villager, 45, explains how he was beaten by the Burmese army, and how he was forced to flee his village with his family:

We, everyone in the family – my wife Mi Nyo, 39, my eldest son Mon Htaw, 25, younger son Min Sin Non, my youngest son Min Win Oo, 1, and my two younger daughters, aged 18 and 12 respectively – moved here to Pa-nan-pon village. In Alaesakhan village, three months ago, there was a recruitment for the militia. When we, a group of friends, criticized that [the recruitment], the village head, Nai Par Dut, who is also the militia leader, told the Burmese army. Then, they, the army, came to beat us – a total of five friends. Of the five, two friends, named Nai Ton Lain and Nai Nyut, had to leave with the army, and no one heard about them. Later, we heard that they were killed. After that, because I had heard that I would be also arrested, we, the entire family, ran here, to Pa-nan-pon village [an IDP site].

Nai Mon was lucky in that the physical abuse inflicted upon him didn’t result in severe injuries or death. Mi Than Nu’s, 34, an Alaesakhan villager, husband was not so fortunate. On June 21, 2010 she gave an account of her husband’s death and her nephew’s arrest to serve as a human shield for the Burmese troops:

Three of us live here. We do not want to go back to my village. We arrived here [the IDP site] three months ago. I heard that they, the Burmese army, shot my husband, Nai Htun Lain, dead. I went to see the army officer, paid him a lot of money to ask him where my husband was. He [first] replied with nothing. [Later], he said that we [the Burmese army] shot him dead because he criticized the militia recruitment and [the Burmese army] did not like that. Now, I live here with two of my kids; my son Min Nyan Htaw, 9, and my daughter, Mi Bon-mon.

Min Than Nu’s troubles did not end with her husband’s death, though. She continued:

Last month, my nephew was arrested to serve as a porter. His name is Mam Pa-lar Htat. The Burmese army blocked the village entrance the day after a Mon armed group attacked the militia office in the village. He went to their orchard to have a look and slept there during the night. In the morning, he came back to the village because he did not know about the blockage of the village entrance. On the way back home, the SPDC army met him and arrested him to serve as a porter for two days. We went to the village head asking about him. After three days passed, he was released. When we asked him, he told us that the SPDC army used me as a human shield, leading them.

Mam Pa-Lar Htat’s experience in being used as not just a porter but also as a human shield is not uncommon. Portering, carrying equipment for the Burmese army, is often coupled with leading the way. The Burmese army cannot be sure of where or when an attack will befall them from rebel groups. Even more so, the Burmese army is afraid of landmines that have been planted by the rebel groups. This fear for their own lives, elicits their unlawful use of villagers to walk ahead and be the first to get hurt if there are landmines.

On May 21, 2010, Nai Lwin, 39, a Hlar-chaung-pyar villager, who works as a farmer and hunter, recounted how he was ordered to be a human shield, along with other villagers, for Burmese troops:

Here, we have to do whatever we are ordered to do. When the Burmese army does not order their men to work but orders the village head to do so, the village head, in turn, orders two villagers per day to work for the army. Those villagers have to guide the Burmese army and are ordered to walk ahead. We have already guided them many times. We drew to see who is going to guide, and for me, at least one time per month, I have to guide the army. If we have to guide after voting, but do not want to go, we have to pay 5,000 Kyat.

The Burmese army uses various methods of intimidation, especially threats, towards villagers in the eastern border areas. Even knowing that there is a rebel group in the vicinity and not exposing them to the Burmese army prompts torture by the Burmese army. Nai Soe Win, a Ma-kyi villager from Ye Township, who is 26 and works as a medic, explained how he was tortured by the Burmese army and how the villagers had to report to the Burmese army if they spotted rebel groups:

I can not define whether it is safe for us or not. In our village, every villager, if they see a rebel group, they have to report about it to the Burmese army. If they do not report right after seeing the rebels, they will get charged. If the rebel groups are having drinks, enjoying themselves in the orchards, those orchard owners will be charged lots of money and will also be persecuted.

I also was tortured like those orchard owners when I was given a letter from a rebel group. That letter said not to travel out of the village since landmines were planted outside the village. The Burmese [SPDC] army found out about this from the village headman. Finding out about that, the Burmese army arrested me and tortured me throughout the night. I was released after being excruciatingly abused at night and then paying them 300,000 Kyat.

Findings from household surveys taken by the TBBC, document that villagers living in close proximity to Burmese army regiments are the most likely to be abused[2]. Villager’s safety is increasingly threatened by Burmese soldiers’ use as human shields, portering, and indefensible torture to assert control over villagers. Looking after their own welfare, villager were forced to flee their homes.

Travel Restrictions and Impacts on Incomes

Villagers often becomes pawns in the conflict between ethnic armed groups and the Burmese army, being abused and used by both sides. Travel restrictions were often mandated by the Burmese army in local villages; closing village entrances, and forbidding villagers to work or travel unless they held a recommendation later from their village headman. The effect of travel restrictions on livelihoods for these villagers became a tipping point between subsisting and starving.

Nai Soe Win described the problems his village faced, like orchard blockages, resulting in an insufficient income for his family:

When [we heard that] there is a group of rebels around here, the Burmese army closed the villages – restricting travel from one village to the other. Consequently, we cannot work and do not get paid either. Yet, for those who are working in Thailand, their family is able to depend on them – receiving money from them.

The majority [of people] residing in this village work on their betel nut plantations while some have boats, relying on the boats for their livings. We can not go to work on our orchards often. This is because the Burmese [SPDC] blocks the way whereas sometimes the rebel groups reopen the ways. Because of the closure, the villagers cannot go to work, which causes inadequate incomes for the villagers. For the food – the rice – we make an order to boatmen to buy [rice] from Ye town, and the fare [of transportation] is 30,000 Kyat. This year, because the closure of orchards happened often, we could not pick our durian to sell and as a result we lost money.

Nai Htay Win, an Alaesakhan villager was also affected by travel restrictions. On April 24, 2010, Nai Htay Win reported:

There are some problems with traveling. The Burmese army has ordered for the Alaesakhan villagers not to travel out-of-and-in the village often. Sometimes, my wife has to request a permission letter from the village head to go to the woods.

Daw Yin, who was beaten along with her husband by the Burmese army, also mentioned the impact of travel restrictions during her May 29, 2010 interview:

The Burmese army does not come to this village often. They only come here when the situation appears to be unstable. We have our legal ID cards, but they are not useful. We can only travel from one village to another if we obtain a recommendation letter from the village head. Also, we have to get recommendation letters from the village head when we go to our orchard for work.

Nai Lwin, who was used as a human shield by the Burmese Army said,

“If we want to travel outside the village, we have to get recommendation letters from our village head.

For our livings, we depend on hunting and we eat what we can find. We have a farm, which produces about one Tin[3] [of rice]. Last year, we got nothing since we were not allowed to travel to the jungle or to sleep outside the village. So, our paddy was eaten and damaged by wild-boars. Now, we just work, cutting bush in other people’s orchard, hired by them. We are paid 3,000 Kyat per day when hired. But we hardly ever get hired to work.

Restrictions to travel highly affect livelihoods of villagers. Whether tending to an orchard, rice paddy, or fishing, most of these undertakings involve travel outside of their village. And, because most of the villagers’ jobs are agricultural, without constant care, their products will decay. The threat of violence in conjunction with being unable to work at their barely subsistence levels were important factors causing villagers to flee to IDP sites.

Livelihoods at the IDP Sites

Having fled from their homes, the villagers were interviewed in IDP sites, and all of them are still, a year later, forced to depend on the IDP sites. But, these IDP sites do not provide a much better option: there is a scarcity of jobs, safety from outsiders is a major concern, and they have little access to medical care.

Individually interviewed, the residents from the IDP area explained that they had to travel to a town nearby for medical treatment when they have an infection or are ill. Paying for medical care is difficult because of little to no job opportunities. This makes supporting children’s education difficult as well.

Individually interviewed, the residents from the IDP area explained that they had to travel to a town nearby for medical treatment when they have an infection or are ill. Paying for medical care is difficult because of little to no job opportunities. This makes supporting children’s education difficult as well.

Nai Htay Win:

I live here without having anything. For us, whenever we come down with malaria or other infectious diseases, we’ll go to the clinic of Pa-nan-pon village to get medical treatment.

On education, he added:

My children have no education. They had to leave school when I fled here [with them].

According to an interview conducted on June 21, 2010 with Mi Aye Dout, an Alaesakhan villager, 37, who was accused of supporting a rebel group, her entire family fled from her home village, leaving her house, orchard, and other properties behind, while the family is, at the moment, experiencing difficulty providing itself with daily meals and travel back to their native village.

Mi Aye Dout is now residing in an IDP site, worried about her family’s survival after fleeing from home, and leaving their orchard with no one to tend to it:

Having fled here, we have nothing with us. We wanted to sell our orchard, but no one wanted to buy it, so we lost both our orchard and our house, leaving them in the village behind. Now, by selling a small piece of our jewelry, we can survive.

However, if the situation here becomes unstable, we will have to flee again. And, it is very helpful when the medics from the Mon army are around here. If they were not here, we could do nothing – and having nothing [materials] to heal. All of my children went to school when we were in our home village, but now only my daughter goes to school, the Mon school.

IDP sites are a last resort for these villagers. Even as a last resort, all aspects of life for them in these sites are unpredictable; job availability is undependable, medical assistance is lacking, and children’s futures are uncertain, with the majority unable to receive an enduring education.

Fleeing from his home, Nai Mon, who was tortured by the Burmese army, explained the difficulty he faced finding enough rice for daily meals. He also discussed the methods he and his family were forced to use to treat their sick children:

Since we ran away from our village to Pa-nan-pon village, we have lived here by selling what we have and buying food. Now, we can not buy any rice because the Burmese army will confiscate it if they meet us on the way. We can only buy 2-3 Pyi[4] of rice. It is very difficulty for survival. Here, since we do not own any farm or orchard, we can only help other people work. No one will hire you to work.

It is safe for us to live. This is because the Mon army is here. Compared with the safety of living in Alaesakhan village, here is a bit safer than there.

It is safe for us to live. This is because the Mon army is here. Compared with the safety of living in Alaesakhan village, here is a bit safer than there.

Here, there is no doctor or medic yet. And last month, when my kids got sick, we just gave them the herbs that we could find. Now, I am very thankful to you all [the interviewers who visited along with a Mon relief agency] since you brought medicine for us. And, we re-sent our daughter, Mi Khaing, and son, Min Sin Non, to the school in this village.

Mi Than Nu, who fled to an IDP site after her husband was killed by SPDC troops, described worry at how her family would survive, especially how she would take care of her children if they became sick:

I want to go back to Alaesakhan village since I have my sister-in-law there to borrow some money from and ask for some food from her. I will go back to my village when the woods are reopened.

For survival, we have to borrow from others, and sell what we’ve got for daily meals. Here, there are no jobs. Now, as the Mon armies are here, it is safe for us, I think.

Here, we have a clinic but do not have any doctor or medic yet. Before you all arrived here, we bought some tablets, like paracetamol, and gave them to the kids when they were sick.

In her interview, Daw Yin, echoed the hardships of the other interviewers in terms of trying to find enough daily sustenance:

For living, as is convenient, we borrow from others and then pay them back – just like recycling. Yet, when the Burmese army comes to the village, we have to give them 2,000 Kyat for their own food supplies. In one month, we had to pay the Burmese army 2-3 times.

There is no safety living here: we just have to live with the Burmese army when they come here while we also have to live amicably with the rebel groups when they stop by. We have a medic here, but at the moment, she’s gone back to her village.

Our kids live at the monastery because it is good for them to live there, getting the chance to study and have daily meals.

Requests to leave the village from the village headman were necessary no matter where a villager was traveling. According to the interview with Nai Lwin, he had to request a recommendation letter from the village headman in order to get to the IDP camp.

Nai Lwin, revealed that his entire family depends on his income and that they have access to medical care when needed:

We have a medic, but in Yan-Ku village. If we became seriously ill, we had to take a boat that passed through Kywe-thone-nyi-ma village.

There is a primary school in the village and it has two teachers. But, it closes often, and as a result, the school kids’ study is disrupted. Most of the kids do not go to school, and become dropouts.

For our living, we depend on hunting and we eat what we can find. We have a farm, which produces about 1 Tin. Last year, we collected nothing since we are not allowed to travel to the jungle and sleep outside the village. So, our paddy was eaten and damaged by wild boars. Now, we just work, cutting the undergrowth in other people’s orchards, hired by them. We were paid 3,000 Kyat per day when hired. But, we hardly ever get hired to work.

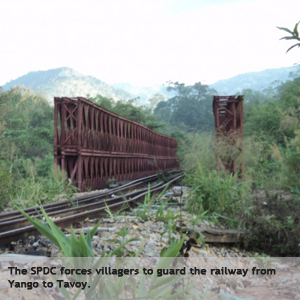

Forced Labor

Besides Nai Lwin, who was forced to porter and be a human shield for the Burmese Army, the other interviewees did not focus on  forced labor in their interviews. Still, staff members from Mon relief agencies working in and around the IDP sites, reported that forced labor is ongoing in villages of Yebyu Township. Pauk-pin-kwin villagers were forced to build fences around the village, to relocate out of the village to the railway station, and to guard the gas pipeline for security purposes. Also, the residents from Khaw Zar sub-township were given direct orders by the Burmese army to construct the office building for the VPDC, where the Burmese army troops would rest. In addition, the Alaesakhan villagers were ordered to go on sentry duty for the gas pipeline successively, while also being forced to build fences.

forced labor in their interviews. Still, staff members from Mon relief agencies working in and around the IDP sites, reported that forced labor is ongoing in villages of Yebyu Township. Pauk-pin-kwin villagers were forced to build fences around the village, to relocate out of the village to the railway station, and to guard the gas pipeline for security purposes. Also, the residents from Khaw Zar sub-township were given direct orders by the Burmese army to construct the office building for the VPDC, where the Burmese army troops would rest. In addition, the Alaesakhan villagers were ordered to go on sentry duty for the gas pipeline successively, while also being forced to build fences.

Conclusion

The percentages of families impacted by military attacks, torture or beatings, arbitrary arrest or detention, forced portering, and military patrols or landmines have increased steadily from 2005 to 2009[5]. IDPs were forced to flee from their villages due to the insufferable crimes against humanity committed against them. By living in an IDP site and not taking the refugee route of leaving Mon State or Tenasserim Division, IDPs are left without resources or contacts, little protection from outside attackers, little or no job opportunities, little or no health care and unstable schooling for IDP children.

In the past TBBC donated emergency assistance in the forms of rice, fish-paste, and cooking oil. Some IDPs received waterproof plastic for temporary roofing on their huts. IDPs used to receive assistance on water and sanitation. The global economic situation has impacted aid funds, and currently, because of that, most IDPs are left to fend for themselves.

According to TBBC’s report, Mon State held 49,050 IDPs and Tenasserim Division held 76,650 IDPs by the end of 2010[6]. Currently, families still live in the IDP areas, though many of the men return home to tend to their orchards, fields, etc. During harvest time, whole families will return home to collect their harvests. Yet, once a harvest is finished, most return to the IDP areas, for the constant fear that their village is not safe from abuse by the Burmese army. IDPs are stuck waiting for the Burmese battalions to leave their home villages.

It will be important to take note of how the proclaimed new government will deal with the IDP population. The new government was instated on April 1, 2011, though a month later, HURFOM reporters can confirm that those IDPs spoken to between April 2010 and June 2010 are still living in IDP sites now in April 2011. The current Burmese government’s assertion that it is a democratic entity has little validity for those IDPs unable to return home. Even with a democratic government, the ongoing civil wars between the ethnic armed groups and the central government’s military will prevent the IDPs from returning to their villages. Only when the Burmese government stops waging war on the ethnic populations, and calls for peace talks to end the civil war, will the IDPs be able to return home and lead stable lives.

[1] Thailand Burma Border Consortium, comp. Protracted Displacement and Chronic Poverty in Eastern Burma/Myanmar. Rep. Chiang Mai: Wanida press, 2010. Print

[2] “TBBC: IDPs: Vulnerability, Coping Strategies & Protection.” TBBC: Thailand Burma Border Consortium: Home Page. Nov. 2009. Web. 13 May 2011. <http://www.tbbc.org/idps/vulnerability.htm>

[3] One Pyi is 2.5 kg and 16 Pyi goes into one Tin. One Tin equals 40 kg.

[4] One pyi is approximately 2.5 kg.

[5] “TBBC: IDPs: Vulnerability, Coping Strategies & Protection.” TBBC: Thailand Burma Border Consortium: Home Page. Nov. 2009. Web. 13 May 2011. <http://www.tbbc.org/idps/vulnerability.htm>.

[6] Thailand Burma Border Consortium, comp. Protracted Displacement and Chronic Poverty in Eastern Burma/Myanmar. Rep. Chiang Mai: Wanidapress, 2010. Print

Comments

Got something to say?

You must be logged in to post a comment.